In this first instalment of the TED (Tired-Exercise-Diet) series, we will explore the intriguing possibility that creatine supplementation, long associated with sports performance, might also play a role in mental health, especially in disorders rooted in shame, self-hate, self-criticism, and general affect dysregulation.

Introducing TED in the NeuroAffective-CBT® Framework – Mirea’s Contribution

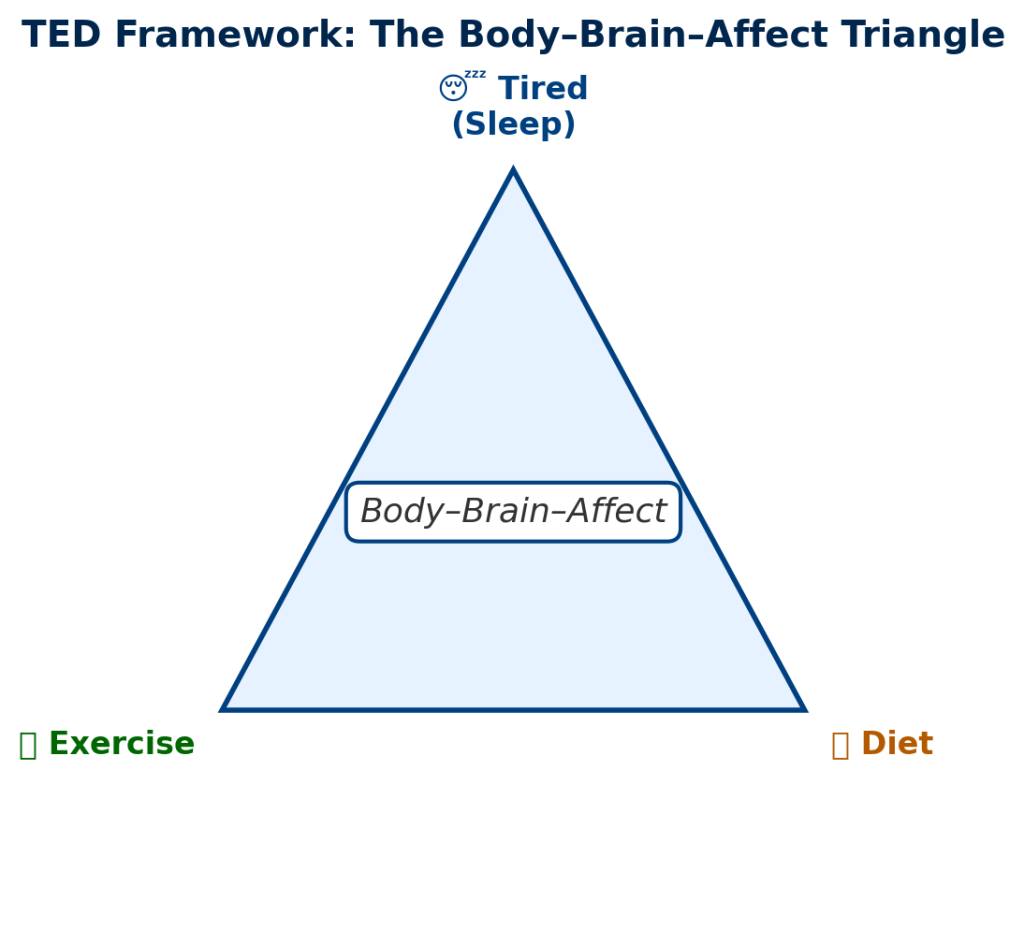

The TED model (Tired-Exercise-Diet) synthesises insights from neuroscience (e.g., gut–brain signalling, reward pathways), nutritional psychiatry, psychophysiology (e.g., sleep deprivation), and behavioural science (habit formation, conditioning). By organising these findings into three core domains, sleep, exercise, and diet, TED provides an accessible, flexible, and evidence-informed structure for lifestyle-oriented intervention.

But TED is not just theoretical: it is publicly presented and described by Daniel Mirea in the NeuroAffective-CBT® literature. Mirea’s “Tired, Exercise and Diet Your Way Out of Trouble” (TED model) is available via ResearchGate, Academia, and the NA-CBT site as a leaflet and white-paper introduction to emotional regulation through lifestyle (Mirea, 2023). In his description, the TED module is positioned centrally within the NA-CBT method, linking body, brain, and affect, the Body–Brain–Affect triangle (Mirea, 2025).

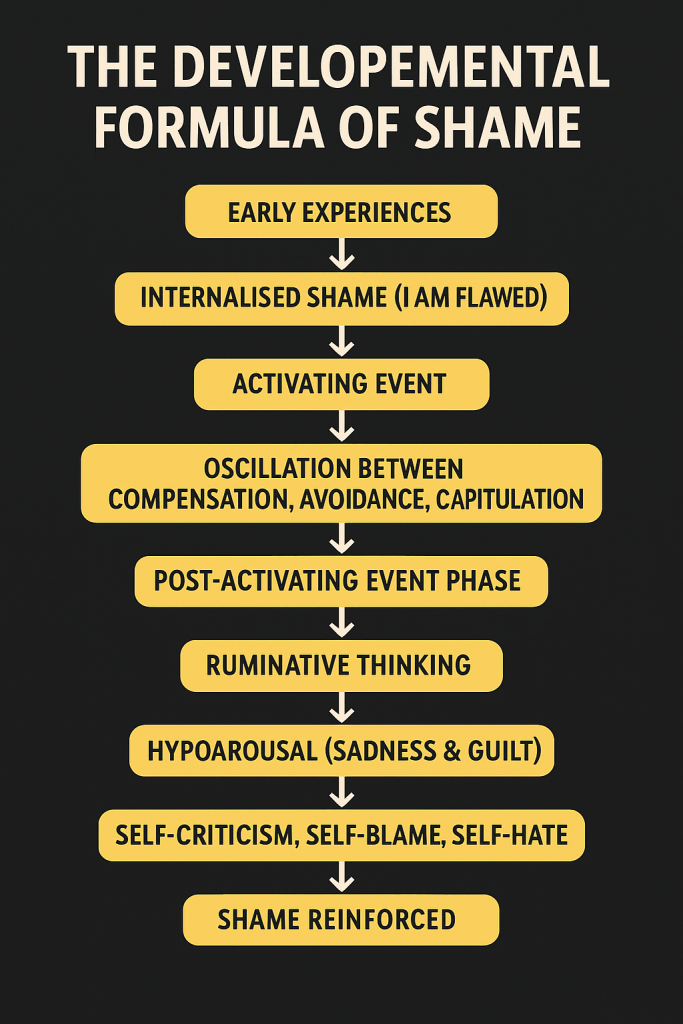

Within the larger NeuroAffective-CBT® programme (comprising six modules), TED is introduced early, immediately after assessment and conceptualisation. NA-CBT specifically targets shame-based disorders such as self-loathing, self-disgust, and low self-esteem, which often underpin psychopathologies like major depressive disorder and anorexia (Mirea, 2023). Addressing lifestyle factors may augment traditional CBT approaches (Firth et al., 2020; Lopresti, 2019).

Empirical evidence shows that improving sleep, increasing physical activity, and enhancing diet quality yield synergistic benefits for emotional regulation, reduction of maladaptive cravings, and improvement of self-esteem (Kandola et al., 2019; Irwin, 2015).

For clinicians, TED offers a concrete tool: integrate lifestyle domains early, personalise interventions, and use TED to amplify CBT. For researchers, it highlights testable mechanisms and opportunities for controlled trials.

This first part focuses on a lesser-known nutritional agent now attracting neuroscientific attention: creatine, a compound with emerging evidence linking it to neuroenergetics and mental health (Candow et al., 2022; Allen et al., 2024).

Why Creatine? What the Evidence Suggests (and Doesn’t..)

The Rationale: Bioenergetics, Oxidative Stress, and Brain Demand

Creatine helps the body make and recycle energy quickly. It acts like a backup battery for your cells, keeping them charged when energy demand is high. While we often think of creatine as something that helps muscles perform better, the brain also uses a huge amount of energy, about one-fifth of everything the body burns at rest.

In people experiencing depression or anxiety, studies suggest that the brain’s mitochondria (the cell’s “power stations” that turn food into usable energy) often don’t work as efficiently. This can lead to higher levels of oxidative stress – a kind of cellular “wear and tear” caused by unstable oxygen molecules that damage cells over time (Morris et al., 2017).

Taking creatine as a supplement may help the brain’s mitochondria work more efficiently, reduce oxidative stress, and stabilise the brain’s energy balance (Allen et al., 2024). Animal studies show that creatine can reduce stress in brain cells and even decrease depression-like behaviours (Zhang et al., 2023). Research in humans is still early, but the results so far are promising.

💡 In simple TED terms:

Why Creatine Might Help the Brain: Energy and Stress Balance! Creatine may help the brain produce cleaner, steadier energy, while reducing the internal “rust” that builds up from stress and poor metabolism, both of which are key targets in emotional regulation.

Human Evidence: Mood, Cognition, and Stress Conditions

Mood and Depression

Early studies suggest that creatine may help boost the effects of antidepressant medication. In one carefully controlled trial, women who took 5 grams of creatine monohydrate per day alongside their usual SSRI antidepressant showed faster and stronger improvements in mood than those taking a placebo (Lyoo et al., 2012).

Several reviews of this research confirm that creatine seems most effective as an add-on rather than a stand-alone treatment (Allen et al., 2024; L-Kiaux et al., 2024). In other words, creatine may make existing treatments work better, but it is not yet proven to work on its own.

Although there have been no large human trials testing creatine by itself for depression or PTSD, brain-imaging studies show that creatine supplementation increases the brain’s phosphocreatine levels (the stored form of cellular energy). This may help restore low brain-energy levels often found in people with mood disorders (Dechent et al., 1999; Rae & Bröer, 2015).

💡 TED translation: Creatine may act like an energy booster for the brain, helping antidepressants “catch” faster and work more effectively. Within the TED framework, this fits the Diet domain, using nutrition to support energy stability and emotional regulation and, complements therapeutic work in the Affect domain.

Cognition, Memory, and Sleep Deprivation

Research also shows that creatine can help the brain think and react more effectively, especially when it is under pressure. Systematic reviews indicate that creatine can enhance memory, focus, and processing speed in conditions of metabolic stress, such as sleep deprivation, oxygen deprivation, or prolonged mental effort (Avgerinos et al., 2018; McMorris et al., 2017).

In one notable experiment, people who stayed awake all night performed better on reaction-time tasks and reported less mental fatigue after taking creatine (McMorris et al., 2006). These benefits appear strongest in older adults or individuals whose brains are already energy-challenged, for example, due to stress, ageing, or poor sleep (Dolan et al., 2018). In contrast, young, well-rested participants often show little or no change (Simpson & Rawson, 2021).

💡 TED translation: Creatine seems to protect the brain when energy is low during exhaustion, stress, or lack of sleep. This is what we call a reactive emtional state (reactive amygdala). It doesn’t make a healthy, rested brain “smarter,” but it helps a tired brain function more efficiently. In TED terms, it bridges the Tired and Diet domains: improving sleep quality indirectly and supporting cognitive endurance under pressure.

Key Questions & Considerations

Dose, Duration, and Uptake

A few muscle studies, led by Dr. Darren Candow, show that taking 3–5 grams of creatine monohydrate per day is enough to maintain muscle levels once stores are full. To load the system faster, some use about 20 grams per day for 5–7 days, which quickly saturates muscle tissue (Candow et al., 2022; Kreider et al., 2017).

However, the brain takes longer to absorb creatine. Imaging studies suggest that at least 10 grams per day for several weeks may be needed to raise brain levels meaningfully (Dechent et al., 1999; Rae & Bröer, 2015). Because around 95% of the body’s creatine is stored in muscle, the brain receives its share more slowly, which may explain why mood or cognitive effects sometimes take weeks to appear.

💡 TED translation: Creatine needs time to “charge the system”. Like building savings in a bank, the longer and more consistently you invest, the better the returns. Within TED, this reflects the Tired and Diet domains, combining steady supplementation with sleep and nutrition for sustained brain energy.

Sodium and Electrolyte Co-Ingestion

Creatine is carried into cells by a sodium-chloride transporter (called SLC6A8) (Tachikawa et al., 2013). This means that electrolytes, especially sodium, help creatine get where it needs to go. While not yet proven for brain outcomes, pairing creatine with a small amount of electrolyte water or a balanced meal containing sodium may improve absorption.

💡 TED translation: Think of sodium as a helper molecule, like a key that lets creatine into the cell. In TED language, this links Diet with Physiology: hydration, electrolytes, and nutrition work together to optimise energy flow.

Dietary Status

People who eat little or no animal protein, such as vegetarians or vegans, often start with lower creatine stores and therefore show a greater response to supplementation (Candow et al., 2022; Antonio et al., 2021). Interestingly, brain creatine levels appear to stay relatively stable across diet types, which suggests the brain has its own built-in regulation system (Rae & Bröer, 2015).

💡 TED translation: Your baseline diet changes how quickly you benefit from creatine. If you avoid animal foods, your muscles may “fill up” faster when you supplement but the brain keeps itself balanced. This reflects TED’s Diet principle: individualisation matters.

Safety and Misconceptions

Decades of studies confirm that creatine monohydrate is safe for healthy adults. No evidence links standard doses (3–5 g/day) to kidney or liver problems (Kreider et al., 2017; Harvard Health Publishing, 2024). Increases in serum creatinine after supplementation simply reflect higher turnover, not kidney damage.

The often-mentioned hair-loss claim remains unsupported (Antonio et al., 2021). However, clinicians should note that in rare cases, individuals with bipolar disorder have reported manic switching after starting creatine (Silva et al., 2013). These cases are very uncommon but worth monitoring in sensitive populations.

💡 TED translation: Creatine is one of the safest, best-studied supplements in both sport and health science. Still, as with all lifestyle tools, TED encourages personalisation and medical oversight, particularly in those with complex mental-health or metabolic conditions.

Implications for TED and NeuroAffective-CBT®

In clinical settings, creatine can and should be viewed as a supportive tool rather than a replacement for established therapies. The goal is to use it thoughtfully in context, and always alongside medical supervision.

Practical guidelines:

- Screen and personalise: Assess kidney function, diet, and medication interactions before supplementation.

- Adjunctive use: Creatine should complement, not replace, therapy or pharmacological treatment.

- Dosing: A short “loading” phase of 20 g/day for 5–7 days, or a gradual increase of 10–20 g/day over four weeks, can be followed by 3–5 g/day for maintenance (Candow et al., 2022).

- Timing: Best used during periods of sleep loss, cognitive strain, or emotional exhaustion, when the brain’s energy demands are high.

- Integration: Combine with other TED domains, sleep hygiene, structured exercise, and nutrient-dense diet to amplify benefits (Firth et al., 2020).

- Monitor and document: Track mood, focus, and physical function; adapt dosing empirically and contribute data to practice-based research.

💡 TED translation: Creatine fits naturally within the Tired–Exercise–Diet framework as a metabolic support for emotional regulation. TED encourages clinicians to see it not as a “pill for a problem,” but as part of a whole-lifestyle system, where sleep, movement, and nutrition all reinforce psychological recovery.

Summary & Outlook

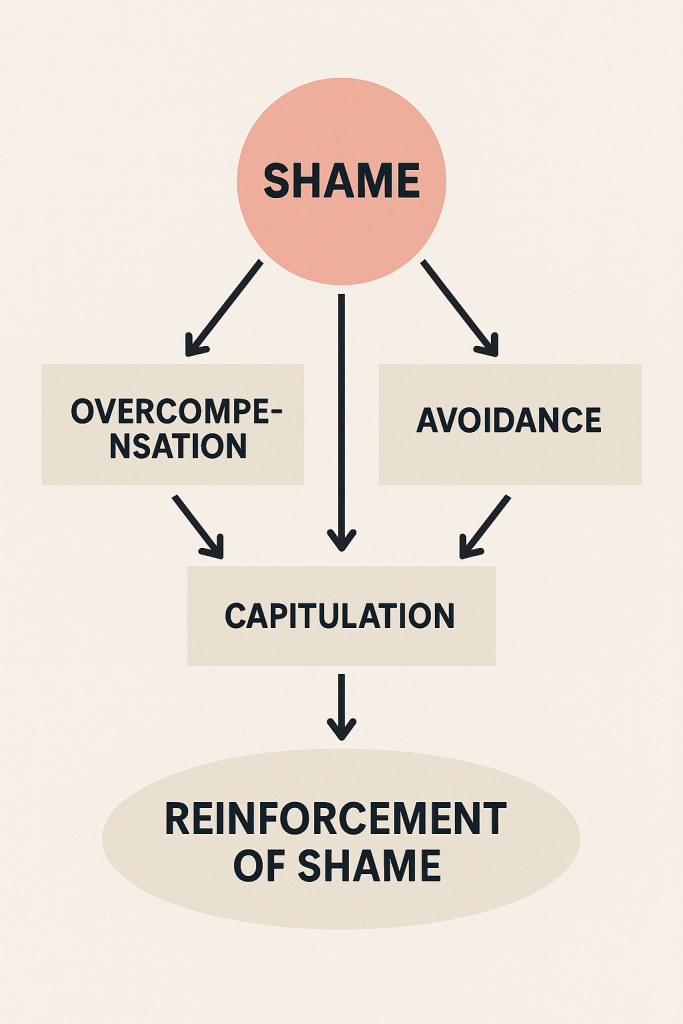

- The TED model (sleep, exercise, diet) offers a practical bridge between psychotherapy and lifestyle science, especially for conditions rooted in shame, self-criticism, and affect dysregulation (Firth et al., 2020; Lopresti, 2019).

- Creatine demonstrates strong scientific plausibility and early clinical promise for improving mood, cognition, and resilience under metabolic stress (Allen et al., 2024; Candow et al., 2022).

- The next step for researchers is to conduct large, placebo-controlled clinical trials testing creatine as an adjunct to CBT for depression and anxiety — ideally with neuroimaging to confirm its effects on brain energy metabolism.

💡 TED translation: Creatine may one day become a recognised “nutritional ally” for the brain, enhancing therapy outcomes by helping clients feel less tired, more focused, and more emotionally stable. For now, it serves as a valuable prototype of how lifestyle science can empower both clinicians and clients to target emotional health from the body upward.

⚠️ Disclaimer:

A final and important reminder: these articles are not intended to replace professional medical or psychological assessment and/or treatment. Regular blood tests and health check-ups with your GP or a private family doctor are essential throughout adult life, in fact increasingly relevant from adolescence onward, given the rising incidence of metabolic and endocrine conditions such as diabetes among young people. It is strongly recommended to seek guidance from qualified professionals, for example, a GP, clinical psychologist, a psychiatrist or depending on your personal goals and needs a registered nutritionist, indeed a NeuroAffective-CBT® therapist, who can interpret your health data (including blood work) and help you understand how your lifestyle, daily habits, and nutritional choices influence your mental and emotional wellbeing.

🧾References:

Allen, P.J., D’Anci, K.E. & Kanarek, R.B., 2024. Creatine supplementation in depression: bioenergetic mechanisms and clinical prospects. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 158, 105308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2024.105308

Antonio, J. et al., 2021. Common questions and misconceptions about creatine supplementation: what does the scientific evidence really show? Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 18(1), 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-021-00412-z

Avgerinos, K.I., Spyrou, N., Bougioukas, K.I. & Kapogiannis, D., 2018. Effects of creatine supplementation on cognitive function of healthy individuals: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Experimental Gerontology, 108, 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2018.04.014

Braissant, O., 2012. Creatine and guanidinoacetate transport at the blood–brain and blood–cerebrospinal-fluid barriers. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease, 35(4), 655–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10545-011-9415-6

Candow, D.G., Forbes, S.C., Chiang, E., Farthing, J.P. & Johnson, P., 2022. Creatine supplementation and aging: physiological responses, safety, and potential benefits. Nutrients, 14(6), 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061218

Dechent, P., Pouwels, P.J.W., Wilken, B., Hanefeld, F. & Frahm, J., 1999. Increase of total creatine in human brain after oral supplementation of creatine monohydrate. American Journal of Physiology – Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 277(3), R698–R704. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.3.R698

Dolan, E., Gualano, B., Rawson, E.S. & Phillips, S.M., 2018. Creatine supplementation and brain function: a systematic review. Psychopharmacology, 235, 2275–2287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-018-4956-2

Firth, J. et al., 2020. A meta-review of “lifestyle psychiatry”: the role of exercise, smoking, diet and sleep in mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 19(3), 360–380. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20773

Harvard Health Publishing, 2024. What is creatine? Harvard Medical School. Available at: https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/what-is-creatine

Irwin, M.R., 2015. Why sleep is important for health: a psychoneuroimmunology perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 143–172. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115205

Kandola, A., Ashdown-Franks, G., Hendrikse, J., Sabiston, C.M. & Stubbs, B., 2019. Physical activity and depression: toward understanding the antidepressant mechanisms of physical activity. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 107, 525–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.09.040

Kreider, R.B. et al., 2017. ISSN position stand: safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 14, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-017-0173-z

L-Kiaux, A., Brachet, P. & Gilloteaux, J., 2024. Creatine for the treatment of depression: preclinical and clinical evidence. Current Neuropharmacology, 22(4), 450–466. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X22666230314101523

Lopresti, A.L., 2019. A review of lifestyle factors that contribute to important pathways in depression: diet, sleep and exercise. Journal of Affective Disorders, 256, 38–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.05.066

Lyoo, I.K. et al., 2012. A randomized, double-blind clinical trial of creatine monohydrate augmentation for major depressive disorder in women. American

Journal of Psychiatry, 169(9), 937–945. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11081259

McMorris, T. et al., 2006. Creatine supplementation and cognitive performance during sleep deprivation. Psychopharmacology, 185(1), 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-005-0269-8

McMorris, T., Harris, R.C., Howard, A. & Jones, M., 2017. Creatine, sleep deprivation, oxygen deprivation and cognition: a review. Journal of Sports Sciences, 35(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2016.1156723

Mirea, D., 2023. Tired, Exercise and Diet Your Way Out of Trouble (T.E.D.) model. NeuroAffective-CBT® Publication. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382274002_Tired_Exercise_and_Diet_Your_Way_Out_of_Trouble_T_E_D_model_by_Mirea [Accessed 17 October 2025]

Mirea, D., 2025. Why your brain makes you crave certain foods (and how “TED” can help you rewire it…). NeuroAffective-CBT, 17 September. [online] Available at: https://neuroaffectivecbt.com/2025/09/17/why-your-brain-makes-you-crave-certain-foods/ [Accessed 17 October 2025].

Morris, G., Berk, M., Carvalho, A.F. et al., 2017. The role of mitochondria in mood disorders: from pathophysiology to novel therapeutics. Bipolar Disorders, 19(7), 577–596. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12534

Rae, C. & Bröer, S., 2015. Creatine as a booster for human brain function. Neurochemistry International, 89, 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2015.07.009

Silva, R. et al., 2013. Mania induced by creatine supplementation in bipolar disorder: case report. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 33(5), 719–721. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182a60792

Simpson, E.J. & Rawson, E.S., 2021. Creatine supplementation and cognitive performance: a critical appraisal. Nutrients, 13(5), 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051505

Tachikawa, M., Fukaya, M., Terasaki, T. & Ohtsuki, S., 2013. Distinct cellular expression of creatine transporter (SLC6A8) in mouse brain. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, 33(5), 836–845. https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2013.6

Zhang, Y., Li, X., Chen, S. & Wang, J., 2023. Creatine and brain health: mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 17, 1176542. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1176542