Welcome to NeuroAffective-CBT®

NeuroAffective-CBT® is the home of evidence-based psychotherapy.. where scientific rigor meets compassion and empathy, and where real, lasting change begins.

“Psychotherapy is an encounter between two emotional beings.

Show me excellent psychotherapy, and I’ll show you a kind and knowledgeable therapist, one willing not only to hear but also feel your pain” – Daniel Mirea

Understanding the Landscape

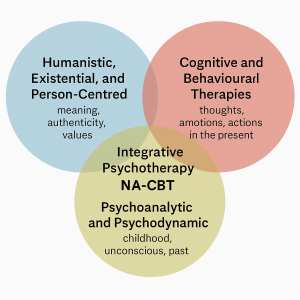

To see where NeuroAffective-CBT® fits, it helps to step back and take a bird’s-eye view of the psychotherapy landscape. Imagine three overlapping circles, each representing one of the field’s major traditions..

-

Humanistic, existential, and person-centred therapies,

focusing on meaning, authenticity, values, and the lived experience of being human. -

Psychoanalytic and psychodynamic therapies,

exploring childhood, attachment, unconscious processes, and the enduring influence of the past. -

Cognitive and behavioural therapies (CBT and its many branches),

targeting thoughts, emotions, and actions in the present.

Where these circles intersect lies the heart of modern psychotherapy. After all, one cannot meaningfully change thoughts or behaviours without understanding a person’s history, values, and aspirations. Likewise, exploring meaning and existence without acknowledging early emotional experiences leaves an incomplete picture. Even psychoanalysis, with its deep focus on the past, ultimately seeks to shape behaviour and choice in the present and future.

The Beauty of Integration

If this sounds intricate, it’s because the field of psychotherapy is wonderfully complex. Different schools of therapy take different paths. Some require years of exploration; others work within weeks or months. Yet all share the same fundamental goal: to help people suffer less, understand themselves more deeply, and live more fully.

NeuroAffective-CBT® (NA-CBT®) belongs to the broad family of cognitive-behavioural therapies, known for their structured frameworks, clear boundaries, and strong empirical foundations. What makes NA-CBT® distinctive is its depth of integration. It weaves together neuroscientific understanding, affective and relational insight from psychodynamic and humanistic traditions, and the practical, outcome-focused methods of behavioural science.

Here, philosophy meets science… The body meets the mind...

Mind, Body, and the Foundations of Change

Many clients enter psychotherapy believing their distress is “all in the mind.” From a NeuroAffective-CBT® perspective, this view is incomplete.

Mind and body form a single regulatory system, and emotional suffering often emerges from how physiological states interact with learned affective patterns.

NA-CBT® is grounded in the understanding that the brain’s core function is prediction in the service of protection. The nervous system is constantly asking: Am I safe? What is about to happen? How bad could it be? These predictions are shaped not only by conscious beliefs and thoughts, but by bodily signals — sleep and rest, movement, metabolic stability, and neurochemical balance.

When physiology is unstable, predictive systems become more threat-sensitive. Neutral events are more easily experienced as dangerous, shame responses are triggered more quickly, and emotions escalate faster and last longer. This is why NA-CBT® integrates TED — Tiredness (sleep and rest), Exercise (movement and fitness), and Diet (metabolism and nutrition) — as a core stabilisation framework within psychotherapy.

TED is not a wellness add-on. It is often the foundation that allows cognitive, emotional, and relational work to become possible, tolerable, and effective.

The Body–Brain–Affect Triangle

Central to NeuroAffective-CBT® is the Body–Brain–Affect triangle , a dynamic system in which each component continuously influences the others:

- Body (Physiology):

Sleep, energy, movement, nutrition, hormonal balance, and nervous system activation provide the biological context in which experience unfolds. - Brain (Prediction and Interpretation):

The brain generates predictions about safety and threat, constructing meaning from bodily signals and emotional states. - Affect (Source of all Emotions):

Fast, survival-oriented emotional responses such as fear, shame, anger, and relief shape attention, behaviour, and self-experience.

Arrows run in all directions between these three points, emphasising reciprocal influence rather than linear causation. A shift in any one corner alters the entire system.

Within this triangle, TED functions as the physiological regulation arm of NA-CBT®, reducing background volatility so deeper psychological learning can occur.

Differentiating Affect from Interpretation

A central therapeutic aim of NeuroAffective-CBT® is helping clients distinguish between:

- Raw affect — the body’s immediate signal of threat, pain, or unmet need

- Interpretation — the meaning the mind assigns to that signal

When affect and interpretation collapse into one another, emotions are experienced as overwhelming, self-defining, or dangerous. Clients may feel that what they feel is what they are.

TED helps slow this process by first asking a more fundamental question:

What is the body signalling right now.. is the reaction accurately calibrated to the present situation?

By stabilising physiological regulation, NeuroAffective-CBT® creates the conditions in which emotions can be felt without being feared, and meanings can be explored without being dictated by threat.

NeuroAffective-CBT® and the Emerging “Fourth Wave”

Within the broader cognitive-behavioural tradition, NeuroAffective-CBT® can be understood as part of an emerging process-based “fourth wave” of psychotherapy. This wave integrates neuroscience, physiology, lifestyle science, and embodied experience into psychological treatment.

While earlier waves of CBT focused on behaviour, cognition, and acceptance, NA-CBT® places affective underlayers such as shame, self-loathing, and internal threat, at the centre of formulation and intervention. Affect is understood as precognitive, fast, and survival-driven. Cognition is the meaning-making layer built upon it.

By working at this level, NeuroAffective-CBT® bridges science and meaning, body and mind, insight and lived experience , offering a psychotherapy that is both deeply human and rigorously evidence-based.