New Research Findings and NeuroAffective-CBT® Implications

In this third instalment of the TED (Tired–Exercise–Diet) Series, we explore how omega-3 fatty acids, particularly EPA and DHA, influence mood, cognition, and emotional regulation. Drawing from neuroscience, nutritional psychiatry, and the NeuroAffective-CBT® framework, this article examines the growing evidence that dietary fats do more than protect the heart, they also nourish the mind. Blending practical TED applications with current clinical research, it offers clinicians and readers accessible strategies for integrating omega-3s into a new lifestyle-based approach to mental health.

Introducing TED in the NeuroAffective-CBT® Framework

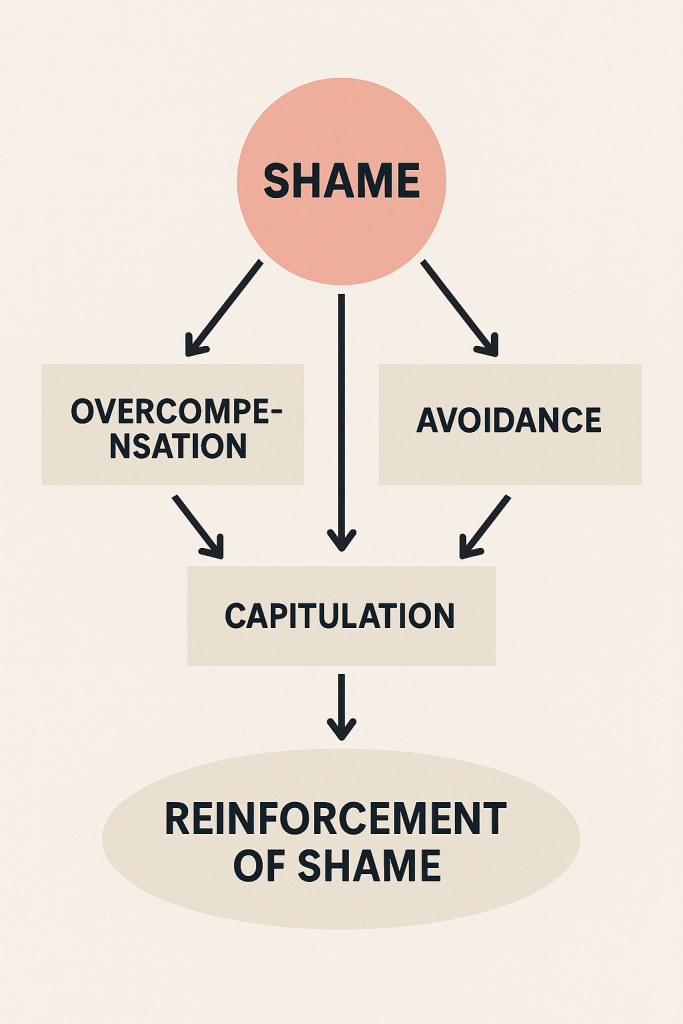

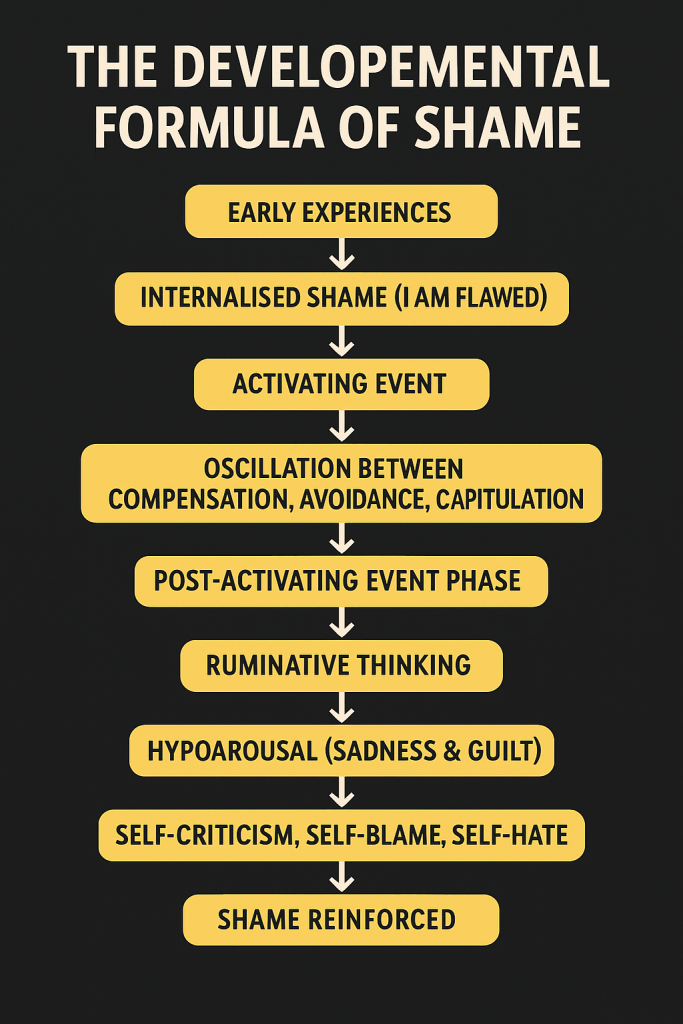

The TED (Tired–Exercise–Diet) model brings neuroscience, nutritional psychiatry, psychophysiology, and behavioural science into an integrated framework for emotional regulation and mental health. Within the broader NeuroAffective-CBT® (NA-CBT) programme, TED is introduced early to support self-regulation and biological stability, the “Body–Brain–Affect” triangle that underpins shame-based and affective disorders (Mirea, 2023; Mirea, 2025).

Earlier parts of this series explored the roles of creatine and insulin regulation in mood and cognition. This third instalment turns to omega-3 fatty acids, essential nutrients that play a central role in brain health, mood regulation, and anti-inflammatory balance.

Why Omega-3s Matter: The Brain’s Structural Fat

When people hear the word “fat,” they often think of storage fat the kind that accumulates around the waist or organs. But the brain depends on an entirely different type: structural fat, which makes up the cell membranes of neurons. These membranes control how signals and chemicals move between brain cells, and their flexibility directly affects how efficiently neurons communicate (Huberman, 2023).

Omega-3 fatty acids, primarily EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) are the building blocks of these membranes. DHA maintains the structure of neurons, while EPA modulates inflammation and neurotransmission, influencing serotonin and dopamine signalling (Freeman et al., 2006; Mocking et al., 2020).

From a TED perspective, this is where Diet meets Affect: better membrane health and lower inflammation translate into improved emotional regulation, resilience to stress, and more stable mood patterns.

🧬 What Are EPA and DHA? (In Simple Terms)

When we talk about omega-3 fatty acids, we’re mostly referring to two main types that the body uses for brain and heart health:

- EPA (Eicosapentaenoic Acid): Think of EPA as the firefighter in your system. It helps reduce inflammation, calm overactive stress responses, and balance the brain’s chemical messengers that affect mood. Studies show that getting enough EPA can help lift low mood and reduce symptoms of depression.

- DHA (Docosahexaenoic Acid): DHA is more like the architect of your brain. It builds and maintains the structure of your brain cells, especially in areas responsible for memory, focus, and emotional stability. It’s crucial for brain development, but also for keeping adult brains flexible and resilient under stress.

Both EPA and DHA work together , EPA helps your brain feel better, and DHA helps it work better. You can get them from oily fish like salmon, sardines, and mackerel, or from algal oil if you follow a plant-based diet.

💡 TED Translation:

EPA supports the Diet part of TED by reducing emotional inflammation, those biochemical “storms” that make you feel tense or flat. DHA supports the Tired part, helping your brain stay sharp and recover faster when you’re mentally drained. Together, they strengthen the brain–body connection that TED and NeuroAffective-CBT® aim to restore. It is important to note that these supplements do not cure mental health conditions but can operate as adjuncts to therapy and medication, supporting recovery and prevention.

🔬 Evidence from Research: Depression, Focus, and Emotional Health

EPA and Depression – What Research Shows

A growing number of studies show that omega-3 supplements rich in EPA (about 1 gram per day) can noticeably reduce symptoms of depression. In some cases, the improvements are similar to those seen with common antidepressant medications in people with mild to moderate depression (Peet & Horrobin, 2002; Martins, 2009; Mocking et al., 2020).

One major study compared 1 gram of EPA to fluoxetine (Prozac), a widely used SSRI antidepressant and found that both worked equally well in improving mood. The group that combined EPA and fluoxetine together did even better, suggesting that omega-3s may enhance the effects of antidepressant treatment (Nemets et al., 2006).

Scientists believe EPA helps mood in several ways. It reduces inflammation in the body and brain (which can interfere with mood-regulating chemicals like serotonin) and keeps brain cell membranes flexible, allowing signals to travel more efficiently between neurons (Su et al., 2018).

💡 TED Translation:

In TED terms, EPA acts like a “mood stabiliser” for the body–brain system, calming internal inflammation, improving brain energy flow, and helping emotions move more smoothly through the day.

DHA and Cognition – The Brain’s Structural Support

While EPA helps regulate mood and inflammation, DHA focuses more on the structure and performance of brain cells. It’s especially concentrated in brain areas responsible for memory, focus, and emotional balance, such as the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus.

Research shows that people who get enough DHA perform better on memory and attention tasks, particularly older adults or those who normally eat little fish or other omega-3 sources (Yurko-Mauro et al., 2010). DHA helps brain cells maintain flexible outer membranes, allowing them to communicate efficiently and adapt to new information, a process linked to learning and resilience.

When DHA levels are low, brain signalling can become sluggish, affecting concentration, motivation, and even emotional stability. Regular intake through food (like oily fish) or supplements can help restore this “neural flexibility.”

💡 TED Translation:

In TED language, DHA supports the Tired and Diet domains, it helps the brain stay sharp, focused, and emotionally steady, especially under mental fatigue or stress. Think of it as giving your neurons the healthy fat insulation they need to keep your thoughts and emotions running smoothly.

⚖️ Dosage, Ratios, and Practical Guidance

Most research suggests that taking between 1,000 and 2,000 mg per day of omega-3 fatty acids, especially formulations higher in EPA, can noticeably improve mood, focus, and general wellbeing (Martins, 2009; Mocking et al., 2020). For depression and emotional balance, experts often recommend that EPA make up at least 60% of the total omega-3 blend.

You can get these healthy fats from both food and supplements:

- 🐟 Natural sources: oily fish such as salmon, sardines, mackerel, and anchovies.

- 🌱 Plant-based options: chia seeds, flaxseed, walnuts, and algal oil (a vegan source rich in DHA).

- 💊 Supplements: choose products that are molecularly distilled or third-party tested for purity and heavy-metal safety.

Because omega-3s are fat-soluble, they are best absorbed when taken with meals that include some healthy fat, such as avocado, eggs, or olive oil.

💡 TED Translation:

Omega-3s are like the high-quality oil in your brain’s engine, helping neurons glide, communicate, and self-repair. For best results, pair consistent intake with the other TED elements: regular sleep (Tired), sports (Exercise), and nutrient-dense meals (Diet).

TED Practical Layer: Combining Nutrition with Behaviour

The TED approach is about how we live, not just what we take. Omega-3s work best when integrated into daily habits that support absorption, brain function, and emotional balance.

Here are a few practical ways to make that happen:

- Take omega-3s with meals that contain healthy fats.

These fats, like those from eggs, olive oil, or avocado, help your body absorb EPA and DHA more efficiently. - Pair with regular movement.

Exercise increases enzymes that help omega-3s get into brain cells (Dyall, 2014). Even short daily walks or light strength training enhance this process. - Balance omega-6 intake.

Many modern diets contain too much omega-6 (from seed oils and processed foods), which can block omega-3 benefits. Aim for a lower omega-6 to omega-3 ratio (around 3:1) to reduce inflammation and support mood regulation (Simopoulos, 2016). - Track mood and focus.

Keep a brief weekly log of your energy, sleep, and emotional stability. Over a month or two, most people notice more mental clarity and steadier mood.

💡 TED Translation:

Small, consistent actions matter. Taking omega-3s in the morning, walking regularly, and eating real, unprocessed foods all work together to open up the body–brain–affect loop, the very system TED aims to strengthen.

TED and NeuroAffective-CBT® Integration

In the NeuroAffective-CBT® (NA-CBT) framework, the TED model (Tired, Exercise, Diet) bridges the gap between the mind and body. Omega-3 supplementation fits naturally within the Diet domain, but its effects ripple across all three.

Low omega-3 levels have been linked to mood dysregulation, impulsivity, and emotional reactivity — all central features of the body–brain–affect triangle that NA-CBT helps regulate (Mirea, 2025). Supporting neuronal health through dietary means therefore complements core CBT processes such as emotional awareness, behavioural activation, and self-compassion.

For clinicians, this integration can be structured through a few evidence-informed steps:

- Screen for dietary insufficiency or inflammation markers (e.g., high omega-6 intake, poor diet quality).

- Psychoeducate clients on the body–mind connection — explain how stabilising the body’s biochemistry supports cognitive flexibility.

- Encourage gradual habit stacking, introducing omega-3s alongside TED routines (sleep hygiene, consistent exercise).

- Monitor outcomes, tracking not just mood changes, but energy, focus, and emotional resilience.

💡 TED Translation:

Think of omega-3s as emotional lubricants, subtle but powerful agents that help the brain’s communication systems run smoothly, making it easier for CBT tools to “click.” Combined with good sleep and movement, they form part of a whole-person therapy that builds physiological and psychological balance from the inside out.

Summary & Outlook

The evidence around omega-3 fatty acids, particularly EPA and DHA, continues to grow, positioning them as safe, low-cost, and biologically plausible adjuncts for improving mood, cognition, and emotional regulation. In depression, EPA-dominant formulations (~1 g/day) have demonstrated antidepressant effects comparable to SSRIs in mild-to-moderate cases (Nemets et al., 2006; Mocking et al., 2020). DHA, on the other hand, plays a structural and neuroprotective role, supporting long-term cognitive resilience.

From the TED viewpoint, omega-3s bridge physiology and psychology. They not only support neuronal efficiency but also improve the emotional flexibility required for therapeutic change — embodying TED’s principle that lifestyle science and psychotherapy are most effective when integrated.

Within the TED (Tired–Exercise–Diet) framework, omega-3s exemplify how dietary micro-interventions can amplify psychotherapeutic outcomes. Combined with good sleep, consistent exercise, and emotional processing, the three TED pillars, they help restore the physiological stability necessary for deeper psychological change.

For clinicians, the takeaway is practical:

- Screen for dietary quality and omega-3 intake early in assessment.

- Encourage balanced omega-3 to omega-6 ratios.

- Integrate nutritional strategies alongside CBT interventions.

- Track progress using both subjective (mood, focus) and objective (diet logs) measures.

💡 Final Thought (TED Translation):

Omega-3s don’t just feed the body, they fuel the brain. When woven into the TED lifestyle and NeuroAffective-CBT® framework, they help restore energy, sharpen thinking, and smooth the emotional landscape, supporting the long-term goal of mind–body regulation.

⚠️ Disclaimer

These articles do not replace medical or psychological assessment. Regular health checks, including blood lipid and inflammatory markers, are recommended. Always consult your GP or prescribing clinician before starting supplementation, particularly if taking psychiatric medication or anticoagulants.

🧾 References

Allen, P.J., D’Anci, K.E. & Kanarek, R.B. (2024) ‘Creatine supplementation in depression: bioenergetic mechanisms and clinical prospects’, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 158, 105308.

Dyall, S.C. (2014) ‘Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and the brain: A review of the independent and shared effects of EPA, DHA and ALA’, Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 6, 52.

Freeman, M.P. et al. (2006) ‘Omega-3 fatty acids: Evidence basis for treatment and future research in psychiatry’, Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(12), pp. 1954–1967.

Huberman, A. (2023) Food and Supplements for Mental Health. The Huberman Lab Podcast, Stanford University.

Martins, J.G. (2009) ‘EPA but not DHA appears to be responsible for the efficacy of omega-3 supplementation in depression’, Journal of Affective Disorders, 116(1–2), pp. 137–143.

Mirea, D. (2023) Tired, Exercise and Diet Your Way Out of Trouble (TED Model). NeuroAffective-CBT®. ResearchGate.

Mirea, D. (2025) TED Series, Part III: Omega-3 and Mental Health. NeuroAffective-CBT®. Available at: https://neuroaffectivecbt.com/2025/10/18/ted-series-part-iii-omega-3-and-mental-health/ [Accessed 18 October 2025].

Mocking, R.J.T. et al. (2020) ‘Meta-analysis and meta-regression of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for major depressive disorder’, Translational Psychiatry, 10, 190.

Nemets, B., Stahl, Z. & Belmaker, R.H. (2006) ‘Addition of omega-3 fatty acid to maintenance medication treatment for recurrent unipolar depressive disorder’, American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(6), pp. 1098–1100.

Simopoulos, A.P. (2016) ‘An increase in the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio increases the risk for obesity and metabolic syndrome’, Nutrients, 8(3), 128.

Su, K.P. et al. (2018) ‘Omega-3 fatty acids in major depressive disorder: A preliminary double-blind, placebo-controlled trial’, European Neuropsychopharmacology, 28(4), pp. 502–510.

Yurko-Mauro, K. et al. (2010) ‘Beneficial effects of docosahexaenoic acid on cognition in age-related cognitive decline’, Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 6(6), pp. 456–464.