Daniel Mirea (10 December 2025)

NeuroAffective-CBT® | https://neuroaffectivecbt.com

Abstract

TED is a lifestyle-based self-regulation model within NeuroAffective-CBT® (NA-CBT®), designed to stabilise the Body–Brain–Affect triangle by targeting three powerful yet frequently neglected regulators of emotion: sleep, movement, and diet/metabolism. Framed both as a memorable acronym and as an imaginal “inner friend”, TED translates complex neuroscience into accessible, everyday actions that help individuals regulate mood, reduce cravings, strengthen self-esteem, and calm chronic threat responses.

Rather than replacing the medical–disease model, TED complements it by highlighting underrepresented biological and behavioural factors in psychotherapy: sleep quality, physical activity, metabolic health, and gut–brain communication (Goldstein & Walker, 2014; Jacka, 2017; Kandola et al., 2019). These are conceptualised as neuroaffective regulators that shape dopamine and serotonin function, circadian rhythms, inflammatory pathways, and vagal signalling (Slavich & Irwin, 2014).

Across the previously published TED series, eight instalments explored key pillars and adjuncts in depth (Creatine, Insulin Resistance, Omega-3 Fatty Acids, Magnesium, Vitamin C, Sleep, Exercise, and Nutrition). This final article integrates those findings into a coherent, applied framework, illustrating how TED can be used in assessment, formulation, treatment planning, and ongoing monitoring within NA-CBT®. While summarising converging evidence from neuroscience, nutritional psychiatry, and exercise physiology (Jacka et al., 2017; Stathopoulou et al., 2006; Craft & Perna, 2004), it also identifies priorities for future empirical research.

NeuroAffective-CBT® and TED are presented as part of an emerging, neuroscience-informed “fourth wave” of CBT that is cognitive, behavioural, affective, and deeply embodied.

Keywords: NeuroAffective-CBT; TED model; sleep; exercise; diet; emotional regulation; lifestyle science; neuroaffective psychotherapy.

Clinician Summary

What is TED?

TED (Tired–Exercise–Diet) is a lifestyle-based self-regulation framework at the heart of NeuroAffective-CBT®. It targets three key neuroaffective regulators: sleep and rest (Tired), movement and physical strengthening (Exercise), and diet/metabolism (Diet).

How is TED used?

TED operates in three interlocking ways:

- as a checklist for physiological contributors to distress (“How tired am I? How much have I moved? What have I eaten and drunk today?”)

- as an imaginal inner coach that reminds clients to “Tired–Exercise–Diet your way out of trouble” in moments of overwhelm, shame, or hopelessness

- as a framework for integrating sleep, movement, and nutrition into assessment, formulation, treatment planning, and relapse prevention

Why does TED matter?

By improving sleep, movement, and diet, TED reduces physiological volatility, supports more stable dopamine and serotonin function, and calms threat and prediction systems. This embodied stability makes it easier for clients to benefit from core CBT techniques such as behavioural activation, cognitive restructuring, and exposure.

How does TED relate to medical care?

TED is not a replacement for medical care, pharmacotherapy, or other specialist input. It offers a practical, neuroscience-informed way for clinicians to bring lifestyle science into therapy while working collaboratively with GPs, psychiatrists, endocrinologists, and nutrition professionals.

Introduction: From Cinema TED to Clinical TED

In the adult comedy TED, a handsome yet emotionally struggling “alpha-male” forms an unlikely but deeply supportive bond with a small, wisecracking teddy bear, also called Ted. Despite his colourful vocabulary, Ted the bear becomes a reliable guide through crises, a companion the protagonist relies on when life becomes chaotic and overwhelming. He is flawed, humorous, sometimes inappropriate, but ultimately loyal and protective.

The TED model in NeuroAffective-CBT® borrows from this metaphor. TED is introduced as an imaginal trusted friend or inner coach who reminds us to “Tired–Exercise–Diet your way out of trouble” when emotions feel overwhelming. Clinically, TED operates in three interlocking ways:

- As a checklist – a rapid screen of sleep, movement, and diet/metabolism:

How tired am I? How much have I moved? What have I eaten and drunk today? - As an imaginal inner coach – a supportive internal friendly figure (e.g. could be, Ted the friendly teddy bear) who nudges clients toward self-care when the mind is flooded with shame, fear, or hopelessness.

- As a structured framework – a systematic method for integrating sleep, movement, and nutritional factors into assessment, formulation, intervention, and relapse-prevention work, ensuring that key physiological regulators of affect are addressed alongside cognitive and emotional processes.

Before describing TED in detail, it is helpful to situate it within the broader context of NeuroAffective-CBT® and an emerging fourth wave of CBT.

Beyond the Medical-Disease Model: Context and Rationale

The dominant approach to psychopathology for many decades has been the medical–disease model, which frames conditions such as depression and anxiety primarily in terms of disorders of brain chemistry. In this view, dysregulation of neurotransmitters like serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine is considered central, and treatment often focuses on pharmacological interventions designed to increase their availability or modify their signalling.

Psychiatrically prescribed medication can be life-saving and remains an essential part of treatment for many individuals struggling with mental illness. However, this model has clear limitations. It tends to downplay psychosocial, lifestyle, and environmental contributors to mental health; it risks reinforcing a passive identity (“my brain chemicals are a mess… I am broken ”) and under-emphasising agency, context, and learning; and it often neglects the emerging evidence around gut–brain communication (Mirea, 2024), inflammation (Slavich & Irwin, 2014), glucose metabolism (Inchauspe, 2023), and physical activity (Kandola et al., 2019) as major determinants of emotional regulation.

For example, approximately 95% of the body’s serotonin is produced in the gut rather than the brain. The gut microbiome can produce GABA, a key inhibitory neurotransmitter that supports calm and relaxation. Gut health and mental health are therefore intimately linked, and interventions such as increased intake of natural pre- and probiotic foods (Greek yoghurt, kefir, garlic, green bananas, sauerkraut and others) can influence emotional states in ways that are not merely psychological but physiologically grounded (Jacka, 2017; Marx et al., 2017).

At the same time, converging evidence indicates that sleep deprivation, physical inactivity, and diets high in refined carbohydrates and added sugars profoundly affect mood, cognition, and affect regulation (Baglioni et al., 2011; Walker, 2017; Lassale et al., 2019). NA-CBT® and the TED model arise from the need to bring these lifestyle dimensions to the centre of psychotherapy, rather than treating them as optional “wellbeing tips” or peripheral lifestyle advice. TED proposes that in order to understand emotional dysregulation, and to support sustainable change, we must consider how a person sleeps, moves, and eats as integral components of case formulation and treatment.

NeuroAffective-CBT® and the Emergence of a Fourth Wave

NeuroAffective-CBT® is an integrative, transdiagnostic model that remains rooted in the evidence base of CBT while extending it in several important ways. As an extension of evidence-based CBT (Hofmann et al., 2012), NeuroAffective-CBT® integrates affective neuroscience and lifestyle science to address physiological and emotional regulation more comprehensively. It focuses explicitly on subclinical affective underlayers such as shame, self-loathing, and internal threat, which often cut across diagnostic categories and are central to chronic distress (Mirea, 2018a; Mirea, 2018b). It is grounded in a neuroaffective perspective that views the brain’s core function as prediction and protection (McEwen, 2007). Cognition and affect are understood as inseparable: affect acts as the organism’s rapid error-signalling system, whereas cognition forms the interpretative and meaning-making layer built upon it.

NA-CBT® emphasises the Body–Brain–Affect triangle, recognising that physiological states shape emotional and cognitive processes and that emotions, thoughts, and behaviours in turn shape physiological states. Within the broader CBT tradition, NA-CBT® and TED can be seen as part of an emerging fourth wave:

- First wave: behavioural conditioning and observable learning.

- Second wave: cognitive restructuring and the link between thoughts and emotions.

- Third wave: contextual and acceptance-based models such as ACT, DBT, and mindfulness-based approaches.

- Fourth wave (emerging): neuroscience-informed, transdiagnostic, and embodied CBT that integrates brain, body, lifestyle science, and authentic living (e.g., NeuroAffective-CBT®, Hypno-CBT®, Strength-based CBT, Process-based CBT).

This fourth wave synthesises and extends earlier CBT developments and incorporates insights from neuroscience, physiology, metabolism, and lifestyle science (Jacka, 2017; Kandola et al., 2019; Walker, 2017). It also examines macro-level contextual factors such as digitalisation and the increasing presence of AI, and how these shape attention, craving, emotional regulation, and interpersonal connection (Yang et al., 2016). NA-CBT® positions itself at this intersection, with TED serving as the practical lifestyle-regulation arm.

Beyond the TED framework, NeuroAffective-CBT® contributes several distinctive features to the emerging fourth wave of CBT. It places affective underlayers such as shame, self-loathing, and internal threat at the centre of formulation and intervention, offering a level of affective precision not typically found in traditional or third-wave models. Its Pendulum-Effect formulation provides a dynamic map of overcompensation, avoidance, and capitulation patterns, linking them directly to core affect and physiological states. NA-CBT® uniquely integrates subcortical affective neuroscience, positioning precognitive affect, not cognition, as the first layer of experience. Its prediction–protection model reframes symptoms as miscalibrated survival strategies rather than distortions or deficits. Through modules such as the Integrated Self, it emphasises identity consolidation and self-repair, complementing but extending beyond ACT or mindfulness-based work. Finally, NA-CBT® offers a deeply embodied perspective through the Body–Brain–Affect triangle, using physiological stabilisation as a prerequisite for cognitive and emotional change. Together, these contributions position NA-CBT® as a distinctive and fully articulated example of fourth-wave CBT.

Affect, Emotion and Regulation in NA-CBT®

Affect regulation refers to the ability to influence more primitive feeling states and bodily arousal using skills such as cognitive reappraisal, mindfulness, imagery, grounding, expressive work, and soothing behaviours (Palmer & Alfano, 2017). Emotion regulation, in contrast, involves the capacity to notice, label, interpret, and intentionally modulate specific emotions as they arise, integrating appraisal, meaning-making, and deliberate behavioural choices in response to internal or external cues.

Within NeuroAffective-CBT®, these processes are understood through the prediction–protection model. The brain is constantly predicting threat or safety, using prior learning to anticipate what will happen next and how dangerous it might be. The body’s signals would heavily shape what the brain predicts. When physiological systems become dysregulated, because of poor sleep, low movement, glucose instability, or inflammatory dietary patterns, the brain becomes more sensitive to threat cues and more prone to false alarms. Neutral events begin to feel dangerous, interpersonal signals are more easily misinterpreted, and emotional reactions tend to rise faster and hit harder.

TED was introduced more than fifteen years ago as a module within NA-CBT® precisely to stabilise these underlying physiological contributors to emotional volatility. By focusing on three lifestyle domains with particularly strong evidence bases, sleep/rest, physical activity, and diet/metabolism (Baglioni et al., 2011; Craft & Perna, 2004; Jacka et al., 2017), TED offers a practical route for reducing physiological volatility and supporting emotional steadiness. It provides both a language and a structure that clinicians and clients can use together to understand why emotional regulation sometimes fails and how it can be strengthened.

Hormones, Neurotransmitters, and Emotional Regulation

Hormones exert a significant influence on how reactive, energised, and emotionally sensitive we feel. Cortisol and adrenaline shape stress readiness; thyroid hormones regulate metabolic pace and cognitive clarity; and sex hormones such as oestrogen and testosterone contribute to mood stability, drive, and motivation. Yet hormones form only one layer of a much wider regulatory system that also includes neurotransmitters, neural circuits, lifestyle patterns, and learned psychological skills.

A simple way to explain this to clients is that hormones set the stage, neurotransmitters run the reactions, and thoughts, behaviours, and lifestyle influence both. Hormones establish the background level of sensitivity and reactivity, while neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, GABA, and glutamate govern moment-to-moment emotional responses, motivation, reward, soothing, learning, and intensity (Panksepp, 1998). These biological systems are then shaped and reshaped by experiences, relationships, and daily habits operating from “above” (thinking, interpretation, meaning) and “below” (body, physiology, affect) simultaneously.

Within NeuroAffective-CBT®, emotional regulation is understood as emerging from the interaction between these interconnected levels. At the neural level, the prefrontal cortex supports planning, perspective-taking, and self-control; the amygdala detects threat and salience; and the hippocampus encodes context and meaning. These structures interact through networks of neurotransmitters—serotonin supporting emotional steadiness, dopamine driving motivation and reward learning, GABA providing inhibitory calming, and glutamate facilitating excitation and learning (Panksepp, 1998; Serafini, 2012).

Hormonal systems modulate these neural processes by altering baseline arousal, sensitivity to stress, and metabolic readiness. Lifestyle factors such as sleep, movement, nutrition, blood sugar regulation, shape both hormonal and neurotransmitter environments. Learned psychological skills, such as cognitive restructuring, self-talk, mindfulness, and compassion, help individuals interpret and respond to internal and external events in ways that either escalate or soften emotional arousal.

Hormones therefore influence emotional life, but they do not dictate it. When cortisol is high, for instance, the body enters a stress-ready state; yet whether a person calms themselves, reframes the situation, seeks support, or spirals into panic depends on their skills, histories, and existing neural pathways, not cortisol alone. This perspective is central to NA-CBT®: it reduces a sense of biological fatalism and invites clients to see emotional regulation as a system they can influence rather than a fate imposed by hormones.

Within this model, affect originates in evolutionarily older neural systems. Jaak Panksepp’s (1998) work on primary affective systems proposes that mammals share a set of core subcortical circuits—RAGE (anger), FEAR (threat detection), PANIC/GRIEF (sadness), LUST (attraction and species reproduction), CARE (attachment), SEEKING (curiosity), and PLAY (joy). These systems operate rapidly, pre-cognitively, and in a deeply embodied manner, reflecting the brain’s fundamental role in promoting survival.

When activity from these systems enters conscious awareness, it is experienced as emotion. At this stage, prefrontal and associated cortical networks interpret, label, and contextualise affective signals in relation to memory, beliefs, and social learning. Emotions such as shame and guilt are therefore not primary affects but secondary, cognitively mediated experiences, as they depend on self-reflection and social evaluation.

This distinction is clinically important. It helps therapists and clients recognise that intense feelings often reflect rapid, subcortical affective activations rather than “irrationality” or “character flaws”. It also underscores that emotional regulation must work in both directions: bottom up, through body, affect, and physiology, and top down, through cognition, meaning, and narrative (Palmer & Alfano, 2017).

TED targets this integrated system primarily from the bottom up. By stabilising sleep (Walker, 2017), movement (Craft & Perna, 2004), and nutrition (Jacka et al., 2017), TED reduces physiological volatility, supports more predictable affective responses, and makes higher-order emotional skills easier to access and practise in therapy.

The TED Model: Structure, Metaphor, and Mechanisms

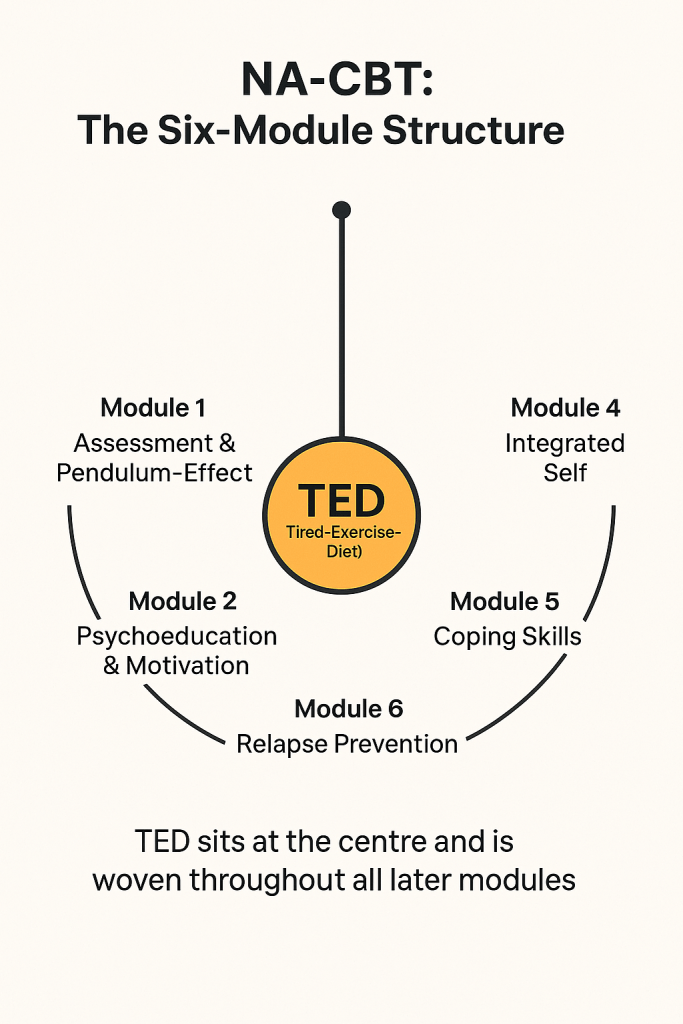

Within NeuroAffective-CBT®, TED occupies a central position. The standard six-module structure of NA-CBT® comprises: Assessment and the Pendulum-Effect formulation; Psychoeducation and Motivation; TED (Tired–Exercise–Diet); the Integrated Self; Coping Skills; and Relapse Prevention. Although presented as discrete modules, the middle sections are conceptualised as intersecting and interchangeable; clinicians are encouraged to move fluidly between them according to client readiness, therapeutic timing, and clinical priorities. The only fixed elements are that therapy begins with a comprehensive assessment and concludes with relapse-prevention planning.

TED is formally introduced in Module 3, but its principles are woven throughout Modules 3 to 6, supporting emotional regulation, cognitive flexibility, and long-term resilience (see Figure 2). Clinically, TED can be summarised in a single phrase: “Tired–Exercise–Diet your way out of trouble.” Yet behind this apparently simple slogan lies a structured framework.

Figure [1]

TED sits at the centre of the model because stabilising sleep, movement, and nutrition provides the physiological foundation required for deeper cognitive, emotional, and behavioural change across all later modules.

There are three main ways in which TED operates. It functions as a checklist: Has this person slept? How well? Have they moved today? What, when, and how have they eaten and drunk? It functions as a personal guide or inner friend: the internal TED who nudges us towards healthier choices when the mind feels overwhelmed or hopeless. And finally, it functions as a framework for assessment, formulation, and intervention, integrating physiological, emotional, and cognitive levels into a coherent plan.

The empirical foundation for TED rests on a substantial body of research showing that sleep quality, physical activity, and diet consistently predict mental health outcomes, including mood, cognitive function, and stress resilience. Studies in student, adult, and clinical samples repeatedly highlight that these “big three” health behaviours are strongly associated with emotional well-being. TED’s contribution is to translate this knowledge into a simple, clinically actionable structure that fits naturally within CBT practice.

With this backdrop, we can turn to the three pillars of TED in more detail.

The “T”: Tired – Sleep and Rest

“T” stands simultaneously for being physically tired and emotionally exhausted. It signals the need to attend to basic sleep hygiene and rest, and it can also carry a motivational subtext: “Aren’t you tired of feeling this way? Let us sleep, exercise, and diet our way out of this.”

Sleep deprivation is now recognised as a central risk factor for a wide range of mental health problems (Baglioni et al., 2011; Mauss et al., 2013). Across decades of research, no major psychiatric condition has been found in which sleep is consistently normal. Everyday experience aligns with this: a parent who has slept poorly commonly reports a “short fuse”, heightened irritability, and emotional reactivity the next day.

Neuroscientific work, including studies from the University of California, Berkeley, has helped clarify why this occurs. When well rested, medial prefrontal regions maintain robust connections with the amygdala, acting as a rational, context-sensitive control system for emotional responses (Goldstein & Walker, 2014). Under sleep deprivation, this connection weakens or “decouples”, leaving the amygdala hyper-reactive and more likely to misinterpret neutral or mildly unpleasant stimuli as threatening (Ben Simon et al., 2020). As a result, individuals become more emotionally volatile with reduced regulatory capacity.

Despite this evidence, sleep is still often under-assessed in psychotherapy. NA-CBT® and TED place sleep at the centre of affect regulation work. Clinically, this includes not only encouraging approximate targets such as eight hours of sleep per night, aligned as far as possible with natural circadian rhythms and dark hours, but also exploring beliefs and emotions around sleep itself. Many clients experience shame and performance anxiety about their sleep, viewing it as another area of failure. Non-punitive sleep logging, focusing on patterns and benefits rather than self-criticism, becomes an important intervention. Psychoeducation based on accessible resources, such as the work of Matthew Walker (Walker, 2017), supports behavioural changes and provides a compelling rationale for prioritising sleep.

TED also draws attention to behaviours that undermine sleep: heavy meals or late strength training close to bedtime, late-night screen use, excessive caffeine, alcohol effects on sleep architecture, and unregulated napping. Addressing these patterns often yields surprisingly rapid improvements not only in fatigue but also in mood, cognitive clarity, concentration, and stress tolerance (Palmer & Alfano, 2017).

Sleep is therefore not a peripheral wellbeing tip but a central determinant of emotional regulation. Within the TED model, stabilising sleep is treated as a primary intervention that reduces baseline physiological volatility, allowing clients to access higher-order cognitive and emotional skills more effectively during therapy.

The “E”: Exercise – Movement and Strength

“E” represents exercise, or more broadly movement and physical strengthening. Regular physical activity is one of the most robust non-pharmacological interventions for mental health (Craft & Perna, 2004; Stathopoulou et al., 2006; Kandola et al., 2019). It supports immune function and hormonal regulation, increases neuroplasticity and brain-derived growth factors, enhances protein synthesis and brain repair, reduces stress hormones, and improves mood. Importantly, it also strengthens self-efficacy and body confidence, which are highly relevant in work with shame and self-loathing.

From an evolutionary perspective, human bodies and brains developed in environments that demanded varied physical activity, not sedentary, screen-based living combined with high-sugar food availability. Our species’ curiosity, resilience, and physical robustness historically supported exploration and survival; TED reintroduces these ingredients in a modern therapeutic context, not as idealised athletic targets but as realistic, sustainable movement practices that support emotional regulation.

Within TED and NA-CBT®, exercise is always tailored to the individual’s age, sex, health status, cultural context, and physical ability. The emphasis falls on daily, sustainable movement, not perfection or performance. Therapy may involve alternating between strengthening and relaxation-focused modalities: for example, combining resistance training, walking, or team sports with practices such as yoga, breath-based techniques, or Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR).

PMR, first described by Edmund Jacobson (Jacobson, 1974), is particularly relevant in NA-CBT®. Clients sequentially tense and relax muscle groups while practising diaphragmatic breathing and focused attention. Over time, they learn to distinguish “tense” from “relaxed” internal states, identify where stress is held in the body, and actively release muscular tension. This somatic awareness often becomes an anchor in emotional regulation work, especially for individuals who struggle to notice early signs of escalation.

Condition-specific approaches can also be used judiciously. Martial arts may support people with low confidence or assertiveness difficulties, providing a structured, embodied context for practising boundaries and power. Team sports can evolve into graded-exposure opportunities for those with social anxiety, allowing contact and cooperation in a meaningful, non-clinical context. In contrast, bodybuilding may be contraindicated for some clients with body dysmorphic disorder where it risks reinforcing preoccupation and compulsive checking. In each case, the task is to co-design a movement plan that honours the client’s values, identity, and health, while gently expanding their sense of agency.

Beyond emotional regulation, exercise directly affects metabolic and reward systems. Regular movement increases muscle mass and therefore glucose-storage capacity, making metabolic stability easier to achieve (Kandola et al., 2019). As insulin sensitivity improves, emotional fluctuations and cravings often reduce. Exercise also influences dopamine pathways associated with motivation, anticipation, and reward learning (Phillips, 2017), contributing to reductions in rumination, anhedonia, and stress reactivity.

In this way, the exercise pillar of TED becomes more than a behavioural recommendation; it is a neuroaffective intervention that shapes physiology, emotion, and cognition simultaneously.

The “D”: Diet – Nutrition, Metabolism, and the Body–Brain-Affect Axis

“D” stands for diet, encompassing both eating and drinking. The link between diet and mental health is surprisingly direct and increasingly well-documented, yet historically it has been underexamined within psychological practice. Food is not simply fuel or a matter of “healthy” versus “unhealthy” choices. It is deeply cultural, embedded in rituals, celebrations, and identity; it is emotional, tied to comfort, attachment, and memories; it is social and sometimes spiritual, woven into community life, values, and fasting practices.

TED recognises this complexity while focusing on the core biological mechanisms through which diet influences emotional regulation, cognition, and motivation. Modern diets in many contexts are high in refined carbohydrates and added sugars. This pattern produces repeated glucose spikes that contribute to increased fat storage, low-grade systemic inflammation, accelerated tissue ageing through glycation, and insulin resistance that can progress to type 2 diabetes. Crucially, early metabolic dysregulation often presents with psychological symptoms such as irritability, anxiety, low motivation, disturbed sleep, reduced libido, fluctuations in mood, and emotional reactivity. It is not uncommon for individuals to be treated for anxiety or depression without screening for metabolic contributors.

Insulin is central to this picture, transporting glucose into liver and muscle cells and, once those are saturated, into fat cells. Regular exercise increases muscle mass and therefore increases glucose-storage capacity, illustrating the synergy between the exercise and diet pillars of TED (Craft & Perna, 2004). As insulin sensitivity improves, blood sugar levels become more stable, and emotional fluctuations and cravings often reduce (Inchauspe, 2023).

From a neurobiological standpoint, sugar dependence can be genuinely difficult to shift. Repeated sugar intake drives dopamine release and reinforces reward learning in patterns that resemble other habit-forming or addictive patterns (Stathopoulou et al., 2006; Wise et al., 2016). Over time, a paradox often emerges: people feel less energised but more dependent on sugar, even as health consequences accumulate.

Emerging research on the gut–brain axis extends this understanding beyond microbiome composition alone. Work by researchers such as Maya Kaelberer has identified specialised neuropod cells in the gut that detect nutrients like glucose and amino acids and convert this detection into fast electrical signals to the brain (Kaelberer et al., 2018). This suggests that the gut can detect genuine metabolic reward and communicate it within milliseconds, helping explain why organisms consistently prefer sugar-water to certain artificial sweeteners even when both taste equally sweet. For clients, this underscores that cravings are not purely “in the mind”; they reflect learned neurobiological patterns linking gut detection, dopamine, and prediction.

Diet quality also interacts with inflammation and depression. Mediterranean-style diets rich in vegetables, fruits, fibre, fish, and healthy fats are associated with reduced depressive symptoms and improved emotional resilience (Jacka et al., 2017; Opie et al., 2018; Lassale et al., 2019). Conversely, ultra-processed, high-sugar diets increase systemic inflammation, a robust predictor of depression, anxiety, and metabolic disorders (Slavich & Irwin, 2014). Diets rich in micronutrients—including B-vitamins, folate, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, magnesium, and vitamin C—support neuroplasticity and new learning, which are central to emotional flexibility in CBT (Serafini, 2012; André et al., 2008).

TED therefore treats diet as a neuroaffective process rather than a purely behavioural one. In clinical work, this may involve exploring not only what people eat but why, when, and how. Beliefs such as “Food is good if it tastes good”, “Eating this makes me a good or bad person”, or “I deserve this after a hard day” are explored gently. Through mindful eating and cognitive reframing, clients learn to soften rigid narratives, reduce guilt, stabilise eating patterns, and cultivate a more compassionate approach to self and nourishment.

Psychological Assessment and Bloodwork Analysis

Although TED is a lifestyle-first framework, it recognises that specific micronutrients can provide meaningful support for mood, energy, and emotional balance when used appropriately. Vitamin C contributes to the synthesis of key neurotransmitters involved in stress and well-being (Serafini, 2012); magnesium supports sleep, muscle relaxation, and anxiety regulation (Palmer & Alfano, 2017); omega-3 fatty acids reduce inflammation and support brain health (Marx et al., 2017); vitamin D plays a central role in immunity and mood stability, particularly in winter months (Lassale et al., 2019); and creatine enhances cellular energy, with emerging evidence for its role in stress tolerance and cognitive functioning (Juneja et al., 2024).

TED does not promote supplements as substitutes for sleep, movement, nutrition, or appropriately prescribed treatment. Rather, it emphasises careful physiological assessment at the outset of therapy, so that these foundational systems can be supported and improved. Many experiences that are often interpreted as purely psychological, fatigue, irritability, low mood, mental fog, anxiety, can in fact arise from underlying physiological issues such as dysregulated blood glucose or early insulin resistance (Jacka, 2017; Inchauspe, 2023), vitamin D deficiency (Lassale et al., 2019), iron deficiency (particularly in women), vitamin B12 insufficiency, magnesium depletion, thyroid dysfunction, or other metabolic irregularities.

For this reason, NeuroAffective-CBT® encourages routine bloodwork early in therapy where possible, alongside collaborative working with GPs, endocrinologists, nutritionists, and even personal trainers when appropriate. CBT psychotherapists, clinical psychologists, and other doctoral-level therapists are not expected to function as nutritionists or physicians. Nevertheless, a working knowledge of the neurobiology of sleep, exercise, and nutrition is increasingly important—not only because these domains interface with the medical–disease model, but because disruptions in these systems are directly relevant to psychological treatment rather than peripheral “wellbeing advice.” Routine blood tests frequently reveal co-occurring issues such as low vitamin D, iron, or B-vitamin levels, as well as untreated or under-treated thyroid dysfunctions (Jacka, 2017). Recognising these patterns does not turn the psychotherapist into a medical prescriber, but it does allow for more informed questioning, clearer integration within case formulation and treatment planning, improved liaison with medical professionals, and compassionate normalisation for clients who struggle to understand why their emotional system may feel chronically overtaxed.

As Figure [2] illustrates, hormones exert a significant influence on how reactive, sensitive, and energised we feel. Cortisol and adrenaline underpin both acute and chronic stress states (McEwen, 2007), shaping irritability, hyper-alertness, and emotional overwhelm. Thyroid hormones, together with dopamine, regulate energy, drive, vitality, and cognitive clarity (Phillips, 2017), while sex hormones such as oestrogen and testosterone play central roles in emotional stability, motivation, confidence, and overall well-being. When these systems drift out of balance, whether through chronic stress, metabolic disturbance, or natural hormonal fluctuations, emotional sensitivity often increases and mood becomes more vulnerable to rapid shifts. Hormonal balance therefore contributes meaningfully to emotional regulation, although it is only one component within a broader regulatory system that also includes neurotransmitters such as serotonin (Serafini, 2012), lifestyle factors such as sleep, movement, and diet (Walker, 2017; Kandola et al., 2019), and learned psychological skills.

Figure [2]

Hormonal balance clearly shapes emotional sensitivity and reactivity.

Hormones are only one part of the regulatory system.

Within the TED model, micronutrients are therefore conceptualised as strategic adjuncts rather than foundations. When they are clinically indicated, medically monitored, and integrated into a comprehensive therapeutic plan, they can help stabilise the physiological terrain on which psychological intervention takes place. By pairing targeted micronutrient science with the core pillars of sleep, movement, and nutrition, TED supports a biologically grounded, holistic approach to emotional health that honours the body–brain integration at the heart of NeuroAffective-CBT®.

Ultimately, this integrated approach helps therapists distinguish between primarily psychological processes and biologically driven symptoms, and to incorporate both levels into their case formulation. Addressing relevant physiological imbalances alongside psychological work often makes treatment more efficient, precise, and sustainable, and offers clients a more coherent explanation for their difficulties and their recovery.

Implementation of TED within NeuroAffective-CBT®

As noted earlier, TED is the third therapy module within the six-module NA-CBT® structure: Assessment and Pendulum-Effect; Psychoeducation and Motivation; TED; the Integrated Self; Coping Skills; and Relapse Prevention. Although presented as separate headings, NA-CBT® conceptualises the middle modules as overlapping and interchangeable. Clinicians are invited to move back and forth between them according to clinical priorities and the client’s readiness. The only fixed points are a thorough assessment at the start and a considered relapse-prevention phase at the end.

The Pendulum-Effect case formulation, introduced during assessment (Mirea, 2018a; Mirea, 2018b), is particularly relevant to TED. It conceptualises self-sabotaging strategies such as, comfort eating, excessive drinking, withdrawal, or overworking, as reinforcing patterns of self-neglect rather than failures of willpower. The formulation maps the dynamic interactions between core affect (e.g., shame, guilt, fear, anger, or disgust), shame-based beliefs and self-loathing narratives, and the maladaptive compensatory strategies of overcompensation, avoidance, and capitulation. It also highlights physiological vulnerabilities such as overeating and metabolic instability (Jacka, 2017), disrupted sleep from rumination (Mauss et al., 2013), and chronically low movement (Kandola et al., 2019). TED is woven through this formulation as both a target of change and a stabilising resource, addressing the physiological factors that maintain the pendulum’s swing. A typical example might be: I overeat alone because it makes me feel better (overcompensation); nobody wants to see me anyway (capitulation); so I might as well stay home and avoid answering invitations or reaching out (avoidance). Over time, these oscillating patterns reinforce the very shame and self-loathing from which they originally attempted to protect.

In early sessions, assessment extends beyond symptoms and cognition to examine sleep patterns and circadian disruption (Walker, 2017), movement levels and physical conditioning (Craft & Perna, 2004), dietary habits and cravings (Inchauspe, 2023), and available medical information such as bloodwork and metabolic markers (Jacka et al., 2017). Given the rising incidence of metabolic difficulties across age groups, NA-CBT® encourages collaborative relationships with healthcare providers and does not restrict itself to a purely psychological lens.

The psychoeducation and motivation module introduces clients to the Brain-Core Function model of prediction and protection (Mirea, 2018a), the Body–Brain–Affect triangle, and the role of sleep, movement, and diet in shaping emotional reactivity, cravings, and cognitive clarity (Walker, 2017; Kandola et al., 2019; Jacka, 2017). TED is framed as an inner friend or supportive internal coach who prompts daily self-checks (“How tired am I?”, “How much have I moved today?”, “What have I eaten and drunk today?”). This externalises self-regulation in a non-shaming, accessible way and helps clients gradually internalise healthier habits.

Goals are then set collaboratively and intentionally kept small, concrete, and measurable. Adjusting bedtime by even twenty or thirty minutes, adding a brief daily walk, bringing forward the last meal of the day, or reducing one marked source of daily glucose spikes can all serve as early steps. These steps are framed as experiments rather than rigid rules, reducing pressure and allowing curiosity and learning to guide change.

Clients are encouraged to track sleep, movement, diet, mood, and cravings between sessions. These logs strengthen self-efficacy and help link physiological changes with emotional and cognitive patterns, supporting the collaborative empiricism at the heart of CBT (Hofmann et al., 2012). TED is then integrated with core CBT interventions such as behavioural activation, cognitive restructuring, exposure and response prevention, and mindfulness or compassion-based practices. As physiological stability improves, clients often find that cognitively and emotionally challenging work becomes more tolerable and more effective.

Applied Practice Examples

Clinical case material helps illustrate how TED operates in practice. One client presenting with volatile mood swings and intense shame spirals showed notable improvement after consistent work on sleep hygiene, including earlier bedtimes, a reduction in evening screen time, lighter evening meals, and increased daylight exposure in the morning. As sleep stabilised, emotional volatility decreased, and the client described feeling “less on edge” and more able to engage with cognitive restructuring.

In another case, a client sought therapy for work-related stress and depression. Their pattern of skipping breakfast, relying on late-night dinners, and consuming multiple teas and coffees during the day contributed to fragmented sleep and reduced workplace efficiency. Tailored psychoeducation, alongside structured changes in sleep routine and meal patterns, led to markedly improved daytime productivity and better stress regulation within weeks. The client’s sense of self-efficacy also increased, making them more willing to address deeper beliefs about worth and failure.

TED’s exercise pillar also plays a role in craving regulation. Regular movement, even at modest levels such as brisk walking or light resistance training, often reduces sugar cravings and ruminative thinking within days. As insulin sensitivity improves and dopamine signalling becomes more stable, the learned association between emotional distress and sugary foods weakens. Clients report feeling less “pulled” towards certain foods and more capable of choosing alternatives that align with their values and health goals. Unplanned benefits often arise: modest weight loss, improved muscle tone, and enhanced physical confidence, all of which support self-appreciation and self-esteem. These early wins are framed not as pressure to “do more” but as evidence of the client’s growing strength and capacity to care for themselves.

Diet-related case examples also highlight the role of beliefs and expectations. In one instance, bloodwork revealed significant iron deficiency in a female client who had labelled her longstanding exhaustion, cognitive fog, and menstrual migraines as “depression.” Psychoeducation about mood, physiology, and the impact of blood loss, combined with appropriate iron supplementation and dietary adjustments, led to marked improvements in energy, anxiety, and confidence over a relatively short period. A problem that had been experienced as a fixed psychological defect was reframed as a largely correctable biological imbalance embedded within a broader emotional context.

TED is particularly helpful in work with shame and self-loathing. In early sessions, clinicians explore these core affects and the resultant self-sabotaging strategies, framing them non-judgementally as understandable, historically adaptive patterns that once protected the client. Comfort eating, for example, may function as a pendulum-like oscillation between overcompensation and capitulation: “I eat to feel better and I stay at home, safely away from people who I believe dislike me anyway.” Excessive drinking, withdrawal, and overworking can operate through similar mechanisms of self-protection that inadvertently become self-neglect. TED enters here as a gentle, embodied pathway into change. When the “mind and heart” feel overwhelmed or intractable, TED redirects attention to the body, which can often be supported more immediately and predictably.

For clients apprehensive about trauma-focused work or deep exploration of shame, TED offers a stabilising starting point. As physiological dysregulation settles and concrete changes accumulate, more complex work, trauma processing, addressing entrenched shame, challenging self-loathing, or revising internalised narratives, becomes safer and less overwhelming. Clients begin to experience themselves as capable of caring for their bodies, which strengthens self-respect, reduces shame, and nurtures a more compassionate relationship with the self.

Implications for Psychotherapy Practice

The TED model offers a range of practical and conceptual advantages for clinicians seeking to integrate lifestyle science into psychotherapeutic work. By positioning sleep, movement, and diet as core regulatory mechanisms rather than secondary lifestyle factors, TED provides a clear framework for understanding how physiological states shape affect, cognition, and behaviour.

First, TED facilitates genuine lifestyle–mental health integration. It invites clinicians to bring questions about sleep, activity, and diet into the heart of case formulation, particularly in cases where emotional dysregulation, chronic shame, or persistent anxiety have not responded sufficiently to cognitive or behavioural strategies alone. By stabilising the body–brain system through targeted lifestyle adjustments, clients often become more receptive to therapeutic interventions and experience improvements in mood, concentration, and resilience that would be difficult to achieve through cognitive work alone.

Second, TED reframes cravings, whether for sugar, carbohydrates, emotional eating, alcohol, or even digital media, as learned, prediction-driven responses rooted in the brain’s reward and metabolic systems. This reframing allows clinicians to normalise cravings rather than judge or pathologise them. Clients learn to see cravings as modifiable neuro-behavioural habits shaped by past learning and current physiology. Behavioural tools such as exposure, response prevention, and habit reversal can then be applied, alongside cognitive strategies for reappraising urges and anticipating triggering contexts, and physiological strategies for stabilising sleep and blood sugar.

Third, TED provides accessible psychoeducational language that demystifies complex neuroscience. Terms such as “tired brain”, “hungry amygdala”, “glucose crash”, “all over the place hormones”, brain predicting threats”, or “inner TED coach” help clients visualise how their physiological state influences their emotional reactions. This clarity typically reduces self-blame, increases motivation, and strengthens the therapeutic alliance. For many clients, TED becomes a daily reference point for self-regulation outside sessions.

Fourth, TED naturally supports motivational work by emphasising small, achievable, and trackable changes. Adjusting bedtime slightly, adding short movement breaks throughout the day, bringing a meal forward, or reducing a single high-glucose food can all be framed as experiments that accumulate into meaningful change. These micro-behaviours provide early wins that reinforce self-efficacy, particularly helpful for clients who feel overwhelmed, hopeless, or stuck in patterns of avoidance and self-criticism.

Fifth, TED aligns seamlessly with third-wave therapies such as ACT, DBT, mindfulness-based interventions, and compassion-focused approaches. It provides the physiological grounding for concepts like acceptance, values-based action, distress tolerance, present-moment awareness, and self-compassion. By stabilising physiological states, TED enhances clients’ capacity to engage in exposure, mindfulness exercises, grounding techniques, and metacognitive work, making psychological flexibility more accessible. At the same time, its explicit integration of neuroscience, lifestyle science, and biologically informed self-regulation positions TED, and NA-CBT® more broadly, not only as compatible with third-wave approaches but as part of a developing fourth wave of CBT in which cognitive, behavioural, affective, and embodied interventions are more fully synthesised.

Finally, TED offers a framework for understanding and responding to the challenges of digital life. Sleep patterns, attention, cravings, and emotional processing are increasingly shaped by screens, notification systems, food delivery ecosystems, and AI-driven attention-capturing loops. TED enables clinicians to help clients explore how digital environments interact with the three pillars: late-night screen use disrupting sleep, sedentary work reducing movement, food delivery apps increasing access to high-glucose foods, and constant online stimulation affecting reward sensitivity and craving. In this way, TED remains relevant to emerging cultural and technological realities.

Using TED in Your Therapy Practice

Early Sessions: Assessment and Hypothesis Building

Dedicate some session time to a structured TED assessment. Map sleep patterns, movement levels, and dietary routines alongside internalised shame, self-loathing, overwhelming affect, and the client’s compensatory, avoidant, or capitulating strategies. Begin developing a hypothesis, such as the Pendulum-Effect formulation, linking physiological dysregulation with emotional volatility and behavioural coping.

Socratic dialogue should be gentle, curious, and function-focused, helping clients discover the purpose behind their patterns rather than defending against judgement. Useful questions include:

- “What does overeating or drinking give you in the short term?”

- “If this behaviour is an overcompensation, what might it be protecting you from feeling?” (overcompensation)

- “When you withdraw or drink alone, what emotion are you moving away from?” (avoidance)

- “Is there a part of you that believes you deserve to feel bad or shouldn’t ask for support?” (capitulation)

- “Where do you see yourself on the pendulum—pushing hard, giving up, or avoiding?”

- “How does poor sleep or unstable blood sugar shape your emotional reactions?”

These questions help uncover the oscillation between overcompensation, capitulation, and avoidance, and set the stage for how TED can stabilise the physiological base that supports emotional regulation.

Early–Middle Sessions: Co-Creating Small, Concrete Experiments Introduce one small, achievable change in each TED pillar, tailored to the client’s readiness, needs, and physical ability. Collaboratively set goals and provide brief psychoeducation that links these changes to emotional regulation, metabolic stability, and bloodwork findings when available. Examples include:

- Bringing bedtime forward by 20–30 minutes, adapted to the client’s lifestyle, routines, and sleep challenges.

- A 10-minute daily walk, structured movement break, or sports activity, chosen in line with the client’s interests, physical ability, and therapeutic goals.

- Moving the last main meal earlier in the day, tailored to the client’s schedule and eating patterns, supported by psychoeducation about glucose regulation and relevant bloodwork findings.

- Taking clinically appropriate supplements indicated by bloodwork (e.g., vitamin D, iron, omega-3, magnesium), always under medical guidance.

- Reducing one predictable source of daily glucose spikes, such as sugary snacks, sugary drinks, or late-night eating.

Encourage the use of simple tracking tools, sleep logs, movement logs, food logs, or continuous/flash glucose monitors where appropriate, to build insight into how physiological shifts influence mood, cravings, and cognitive clarity. These tracking measures support collaborative empiricism and help normalise the link between daily habits and emotional regulation.

Middle Sessions: Linking Physiology to Emotion and Cognition

As clients log sleep, movement, diet, and cravings, use these patterns to illustrate how physiological stability supports emotional steadiness and cognitive flexibility. Help clients notice:

- how improved sleep strengthens emotional tolerance

- how regular movement reduces cravings and rumination

- how steady glucose levels soften shame spirals and urgency

- how nutritional changes affect mood, fatigue, and motivation

Socratic questions deepen insight:

- “What do you notice happens to your mood on days when you sleep better?”

- “How does movement affect the intensity or duration of difficult feelings?”

- “What patterns do you see between your eating rhythms and your triggers?”

TED then becomes a living part of the formulation, showing how stabilising physiology enhances the effectiveness and tolerability of behavioural activation, cognitive restructuring, and exposure work.

Relapse Prevention: Embedding TED as a Long-Term Inner Coach

In the final phase, TED becomes a personalised self-regulation checklist and internal companion. Clients learn to ask themselves:

- “How tired am I?”

- “How much have I moved today?”

- “What have I eaten or drunk that might affect my mood?”

TED is framed as an inner guide—protective, stabilising, and compassionate—rather than a set of behavioural rules. Some clients benefit from using a literal teddy bear or symbol to anchor this internalisation.

In this way, TED supports long-term resilience by strengthening embodied awareness, preventing physiological drift, and sustaining the emotional stability needed for continued psychological growth.

Additional Socratic Questions

The following questions can be adapted depending on the client’s history, readiness, and goals.

Exploring Function and Purpose:

- “What does this behaviour give you in the short term?”

- “What does it help you avoid emotionally?”

- “What happens internally just before the behaviour starts?”

- “If the behaviour could talk, what would it say it is trying to protect you from?”

Exploring Shame and Self-Loathing Underlayers:

- “What does this behaviour say about how you see yourself?”

- “Is there an old belief or story about yourself that gets activated here?”

- “If someone you cared about struggled in this way, how would you interpret their behaviour?”

Exploring the Pendulum-Effect:

- “Where do you notice yourself on the pendulum—pushing hard, giving up, or avoiding?”

- “What triggers a shift from one end of the pendulum to the other?”

- “What would a more balanced middle position look like for you?”

Linking TED to Emotional Patterns:

- “How does your sleep or lack of sleep influence how quickly you reach this behaviour?”

- “Do cravings or urges feel stronger on days when you’ve eaten in a certain way?”

- “When your energy is low, which part of the pendulum do you tend to move toward?”

Building Insight and Motivation:

- “What would change if you had 10% more sleep or energy this week?”

- “Which TED pillar feels easiest to adjust first?”

- “What small shift could help the pendulum swing less violently?”

- “Which of these would feel like the smallest possible step forward?”

- “What would a 10% improvement look like this week?”

- “How will we know if this experiment is helping?”

Limitations and Future Research

While TED is grounded in clinical practice and supported by an existing evidence base drawn from multiple disciplines, dedicated empirical evaluation of TED as a specific framework is still emerging. Future research should include randomised controlled trials comparing standard CBT with NA-CBT® incorporating TED, as well as longitudinal studies tracking lifestyle changes and emotional outcomes over time (Hofmann et al., 2012). Mediation analyses exploring pathways such as improved sleep leading to reduced emotional reactivity (Mauss et al., 2013; Ben Simon et al., 2020) and enhanced self-esteem, or dietary change reducing inflammation and improving mood and cognition (Slavich & Irwin, 2014; Jacka et al., 2017), would be particularly valuable.

Cross-cultural and developmental studies are needed to examine the generalisability of TED across different age groups, cultural contexts, and health systems. Dose–response investigations could clarify the intensity and duration of sleep, exercise, and dietary changes required to produce clinically meaningful improvements (Kandola et al., 2019; Walker, 2017). Mechanistic studies incorporating biomarkers such as inflammatory markers (Slavich & Irwin, 2014), insulin sensitivity indices (Jacka, 2017), microbiome profiles (Marx et al., 2017), and neuroimaging would help map the physiological pathways through which TED exerts its effects. Finally, further work is needed to evaluate micronutrients and supplements as adjuncts, rather than replacements, to psychotherapy and medication within an integrated neuroaffective framework (Marx et al., 2017; Juneja et al., 2024).

Conclusion and Clinical Caveats

NeuroAffective-CBT® remains firmly anchored in the evidence-based strengths of traditional CBT. Its cognitive and behavioural techniques, long proven effective across a wide range of disorders (Hofmann et al., 2012), continue to form the backbone of therapeutic change. TED extends these foundations by highlighting a simple but often overlooked truth: psychological suffering does not occur independently of biology, and emotional healing does not unfold in isolation from the body’s regulatory systems.

Hormones, neurotransmitters, metabolic processes, and sleep–wake rhythms continuously influence how individuals feel, think, and relate. Cortisol affects stress sensitivity (McEwen, 2007); adrenaline heightens fear and readiness; oxytocin fosters bonding and trust. Thyroid hormones, oestrogen, and testosterone support mood stability, motivation, and energy (Phillips, 2017). At the same time, the brain’s regulatory circuits, the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, hippocampus, and associated networks, govern moment-to-moment emotional responses through neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, GABA, and glutamate (Serafini, 2012). Within this landscape, TED fills a critical therapeutic gap by providing a framework that honours the dynamic interplay between biological foundations, affective patterns, learned psychological habits, and behavioural skills.

TED reminds us that hormones may set the stage, neurotransmitters may shape moment-to-moment emotional reactions, and thoughts and habits continually influence both. Emotional regulation arises from the integration of all these systems, not from any single one. By stabilising physiology, improving sleep quality, increasing movement, and optimising nutrition, clients gain access to greater cognitive flexibility, emotional steadiness, and healthier behavioural patterns. This embodied stability allows deeper therapeutic work to take root, including trauma processing, shame reduction, and the reshaping of entrenched beliefs.

As metabolic disturbance, sleep dysregulation, sedentary lifestyles, and nutritional deficiencies increase globally, psychotherapy can no longer afford to ignore the body. The future of effective mental health intervention lies at the intersection of brain, body, affect, and behaviour, exactly where TED is positioned. By integrating lifestyle science with neuroaffective principles, NeuroAffective-CBT® represents an emerging “fourth wave” of CBT: neuroscience-informed, embodied, and responsive to the realities of modern living and one that may be understood philosophically as a movement towards more authentic living.

At the same time, it remains essential to emphasise that TED and related lifestyle interventions do not replace medical care or psychiatric treatment. Routine health checks and bloodwork, especially from adolescence onwards, are vital given rising rates of diabetes, metabolic disorders, and nutritional deficiencies. Supplements should remain adjunctive, ideally used under medical guidance, rather than replacing prescribed medication. TED is best understood as a self-regulation framework that invites clinicians and clients alike to recognise that meaningful psychological change is not purely cognitive; it is profoundly physiological.

By attending to how we sleep, move, and eat, we cultivate not only emotional resilience but also a more compassionate, empowered relationship with the Self. TED offers a concise yet comprehensive way of weaving sleep, movement, and diet into psychotherapy. It bridges neuroscience, lifestyle medicine, and cognitive–behavioural interventions in ways that are accessible to both clinicians and clients. Ultimately, TED encourages us to view physiology as the fertile soil in which psychological change grows, reminding us that lasting transformation is not only a matter of thought but of the whole embodied person.

Clinical Disclaimer

The TED framework and NeuroAffective-CBT® concepts described here are for educational and clinical training purposes only. They do not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Clinicians should work collaboratively with medical professionals when addressing sleep difficulties, metabolic conditions, nutritional deficiencies, or medication. Individuals seeking help for mental or physical health difficulties should consult their GP, psychiatrist, or other appropriate healthcare provider.

References:

André, R.B., Lopes, M. & Fregni, F., 2008. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies on major depression and BDNF levels: Implications for the role of neuroplasticity in depression. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 11, pp.1169–1180.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1461145708009015

Baglioni, C. et al., 2011. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 135(1–3), pp.10–19.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011

Ben Simon, E., Oren, N. & Walker, M.P., 2020. Sleep loss and the waning of affective control. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 33, pp.1–6.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.12.003

Conner, T.S., Brookie, K.L., Richardson, A.C. & Polak, M.A., 2017. On carrots and curiosity: Eating fruit and vegetables is associated with greater flourishing in daily life. British Journal of Health Psychology, 22(2), pp.321–335.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12245

Craft, L.L. & Perna, F.M., 2004. The benefits of exercise for the clinically depressed. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 6(3), pp.104–111.

URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC474733/

Crum, A.J., Corbin, W.R., Brownell, K.D. & Salovey, P., 2011. Mind over milkshakes: Mindset influences how the body responds to food. Health Psychology, 30(5), pp.424–429.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023467

Duman, C.H. & Duman, R.S., 2015. Spine synapse remodeling in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression. Neuroscience Letters, 601, pp.20–29.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2015.01.022

Goldstein, A.N. & Walker, M.P., 2014. The role of sleep in emotional brain function. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, pp.679–708.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153716

Hofmann, S.G. et al., 2012. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(5), pp.427–440.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1

Inchauspe, J., 2023. The Glucose Goddess Method. [Kindle edition].

Jacka, F.N. et al., 2010. Association of Western and traditional diets with depression and anxiety in women. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(3), pp.305–311.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09060881

Jacka, F.N., 2017. Nutritional psychiatry: Where to next? EBioMedicine, 17, pp.24–29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.02.020

Jacka, F.N. et al., 2017. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the SMILES trial). BMC Medicine, 15, p.23.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y

Jacobson, E. (1974). Progressive Relaxation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Juneja, K., Malik, I., Roy, K., Singh, A., Basu, A., Yadav, R. & Singh, S., 2024. Creatine supplementation in depression: A review of mechanisms, efficacy, clinical outcomes and future directions. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 19, p.100592.

Kaelberer, M.M., Buchanan, K.L., Klein, M.E., Barth, B.B., Montoya, M.M., Shen, X. & Bohórquez, D.V., 2018. A gut-brain neural circuit for nutrient sensory transduction. Science, 361(6408), eaat5236.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat5236

Kalmbach, D.A., Pillai, V., Roth, T. & Drake, C.L., 2018. The interplay between daily affect and sleep: A 2-week study of young women. Journal of Sleep Research, 27(1), e12502. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12502

Kandola, A., Ashdown-Franks, G., Hendrikse, J., Sabiston, C.M. & Stubbs, B., 2019. Physical activity and depression: Towards understanding the antidepressant mechanisms. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 107, pp.525–539.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.09.040

Kang, H.J. et al., 2012. Decreased expression of synapse-related genes and loss of synapses in major depressive disorder. Nature Medicine, 18(9), pp.1413–1417.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2886

Lai, J.S. et al., 2014. Dietary patterns and depression in community-dwelling adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 99(1), pp.181–197.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.069880

Lassale, C. et al., 2019. Healthy dietary indices and depressive outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Molecular Psychiatry, 24(7), pp.965–986.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0237-8

Lubans, D.R. et al., 2016. Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: A systematic review of mechanisms. Pediatrics, 138(3), e20161642.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1642

Marx, W. et al., 2017. Nutritional psychiatry: The present state of the evidence. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 76(4), pp.427–436.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665117002025

Mauss, I.B., Troy, A.S. & LeBourgeois, M.K., 2013. Poorer sleep quality is associated with lower emotion-regulation ability. Cognition and Emotion, 27(3), pp.567–576.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2012.727783

McEwen, B.S., 2007. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), pp.873–904.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00041.2006

Mirea, D., 2018a. NeuroAffective-CBT®: Advancing the frontiers of CBT. NeuroAffective-CBT.

URL: https://neuroaffectivecbt.com/2018/07/24/describing-na-cbt/

Mirea, D., 2018b. The Underlayers of NeuroAffective-CBT. Academia.edu.

URL: https://www.academia.edu/40996196/The_underlayers_of_NeuroAffective_CBT_by_Mirea_D

Mirea, D., 2018c. NeuroAffective-CBT for Clinical Perfectionism. ResearchGate.

URL: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382254468

Mirea, D., 2024. If My Gut Could Talk to Me, What Would It Say? NeuroAffective-CBT.

URL: https://neuroaffectivecbt.com/2024/07/12/if-my-gut-could-talk-to-me-what-would-it-say/

Mirea, D., 2025. Why Your Brain Craves Certain Foods (and How TED Can Help You Rewire It…). NeuroAffective-CBT.

URL: https://neuroaffectivecbt.com/2025/09/17/why-your-brain-makes-you-crave-certain-foods/

Mirea, D., 2025. TED Series – Part VII: Physical Exercise, Sports Science and Mental Health. NeuroAffective-CBT. Available at: https://neuroaffectivecbt.com/2025/10/31/ted-series-part-vii-physical-exercise-sports-science-and-mental-health/ [Accessed 27 November 2025].

Opie, R.S., O’Neil, A., Jacka, F.N., Pizzinga, J. & Itsiopoulos, C., 2018. A modified Mediterranean diet for major depression: Feasibility and protocol from the SMILES trial. Nutritional Neuroscience, 21(7), pp.487–501.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.2017.1411320

Panksepp, J. (1998) Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions. New York: Oxford University Press.

Palmer, C.A. & Alfano, C.A., 2017. Sleep and emotion regulation: An organising review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 31, pp.6–16.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2015.12.006

Phillips, C., 2017. Physical activity and neuroplasticity in mood disorders. Neural Plasticity, 2017, Article 7014146.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7014146

Rush, A.J. et al., 2006. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients: A STAR*D report. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(11), pp.1905–1917.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905

Schlitt, J.M., Downes, M., Young, A.I. & James, K., 2022. The “Big Three” health behaviours and mental health in university students. The Canadian Review of Social Studies, 9(1), pp.13–27.

URL: https://thecrsss.com/index.php/Journal/article/view/298

Serafini, G., 2012. Neuroplasticity and major depression: The role of antidepressants. World Journal of Psychiatry, 2(3), pp.49–57.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v2.i3.49

Slavich, G.M. & Irwin, M.R., 2014. From stress to inflammation and depression: A social signal transduction theory. Psychological Bulletin, 140(3), pp.774–815.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035302

Stathopoulou, G., Powers, M.B., Berry, A.C., Smits, J.A.J. & Otto, M.W., 2006. Exercise interventions for mental health: A review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(2), pp.179–193.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00021.x

Walker, M.P., 2017. Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams. London: Penguin Books.

Wise, P.M., Nattress, L., Flammer, L.J. & Beauchamp, G.K., 2016. Reduced sugar intake alters sweet taste intensity but not pleasantness. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 103(1), pp.181–189.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.113605

Yang, C.C. et al., 2016. State and training effects of mindfulness meditation on brain networks. Neural Plasticity, 2016, Article 9504642.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9504642