Why Sleep, Movement, and Metabolic Stability Matter in NeuroAffective-CBT®

Many clients enter psychotherapy believing their distress is “all in the mind”. From a NeuroAffective-CBT® (NA-CBT®) perspective however, this assumption is incomplete. Mind and body form a single regulatory system, and emotional suffering often emerges from how physiological states interact with learned affective patterns.

NA-CBT® is grounded in the idea that the brain’s core function is prediction and protection. The nervous system constantly asks: Am I safe? What is about to happen? How bad could it be? These predictions are shaped not only by thoughts and beliefs, but by bodily signals—sleep, movement, metabolic stability, and neurochemical balance.

When physiology is unstable, prediction systems become more threat-sensitive. Neutral events are more easily experienced as dangerous, shame responses are triggered faster, and emotions escalate more quickly and last longer. This is why NA-CBT® integrates TED—Tiredness (sleep/rest), Exercise (movement/fitness), and Diet (metabolism/nutrition)—as a core stabilisation framework within psychotherapy.

TED is not a wellness add-on. It is often the foundation that allows cognitive, emotional, and relational work to become tolerable and effective.

NeuroAffective-CBT® and the emerging “fourth wave”

Within the broader CBT tradition, NA-CBT® can be understood as part of an emerging, process-based fourth wave, integrating neuroscience, physiology, lifestyle science, and embodied experience into psychological treatment.

While earlier waves of CBT focused on behaviour, cognition, and acceptance, NA-CBT® places affective underlayers such as shame, self-loathing, and internal threat, at the centre of formulation and intervention. Affect is treated as precognitive, fast, and survival-driven; cognition is the meaning-making layer built on top of it.

Central to this model is the Body–Brain–Affect triangle:

- physiological states shape emotional and cognitive processes,

- emotions influence thoughts and behaviour,

- thoughts and behaviours, in turn, reshape physiology.

Within this system, TED functions as the physiological regulation arm of NA-CBT®, reducing background volatility so deeper psychological learning can occur.

Therefore, the central aim of NA-CBT® is helping clients distinguish between:

- raw affect (the body’s immediate threat or pain signal), and

- interpretation (the meaning the mind assigns to that signal)

When these collapse into one another, clients experience emotions as overwhelming, self-defining, or dangerous. TED helps slow this process down by first asking: what is the body signalling right now, and is the reaction accurately calibrated?

Why lifestyle belongs inside psychotherapy

When sleep is poor, movement is minimal, or blood glucose is unstable, clients often experience:

- heightened anxiety or irritability

- emotional reactivity and rumination

- intensified shame and self-criticism

- reduced tolerance for exposure, uncertainty, or intimacy

From an NA-CBT® perspective, these are not failures of willpower or insight. They are signs that the nervous system is operating under strain.

TED aims for sufficiency rather than optimisation. The goal is not perfect habits, but a stable internal environment that reduces threat sensitivity and supports emotional regulation as exemplied in the three case studies below.

Case examples (TED in action)

Case 1: Anxiety amplified by fatigue and metabolic instability

A client with panic-like anxiety noticed that their most intense fear spikes occurred late morning after poor sleep, skipped breakfast, and significantly increased caffeine and sugar intake. Using the TED self-check, they recognised that the fear was only partly warranted and heavily fuelled by tiredness and metabolic volatility. Addressing these factors first—reducing caffeine and sugar, introducing appropriate vitamins and minerals where indicated, and adding a daily morning walk—made later exposure work possible rather than overwhelming.

Case 2: Shame-driven depression softened through movement

Another client with chronic self-loathing noticed that shame spikes reliably followed long sedentary days. Short “exercise snacks” were introduced not as fitness goals, but as identity repair behaviours (“I am someone who cares for my nervous system”). Tracking the relationship between movement, mood, and self-attacks led to reduced shame intensity before deeper cognitive restructuring was attempted.

Case 3: Relationship reactivity reduced through physiological regulation

A client experiencing explosive arguments discovered that intense reactions often followed long workdays, exhaustion, poor sleep, and minimal movement. The TED self-check helped distinguish warranted relational frustration from unwarranted threat amplification, enabling repair conversations instead of escalation.

Assessment and formulation: the Pendulum-Effect model in context

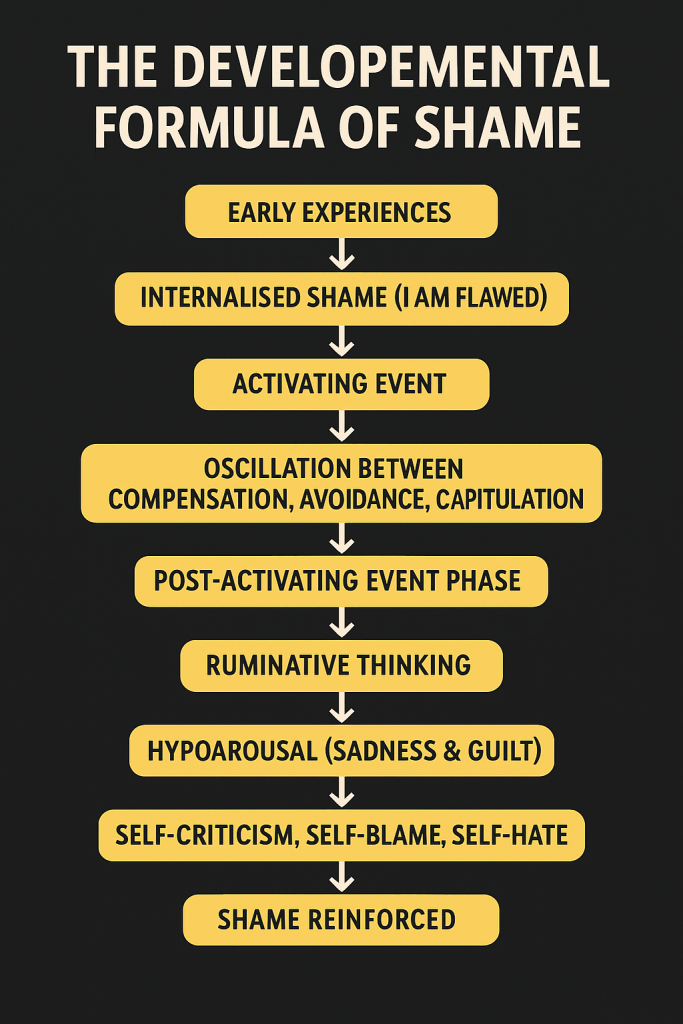

NA-CBT® assessment extends beyond symptoms and surface cognitions to explore developmental affective learning.

A common pattern seen in clients with chronic shame, anxiety, or perfectionism involves early experiences such as: parents were hard to satisfy; poor school results or mistakes led to angry remarks, humiliation, withdrawal of warmth, or visible disappointment.

Over time, the child learns that performance determines safety and acceptance.

Core affect installed: shame

In this environment, a core affect of shame becomes installed. Shame functions as a predictive alarm: “If I fail, I will be exposed, rejected, or humiliated.”

This learning is not primarily cognitive. It is subcortical, embodied, and anticipatory. As adults, these individuals often experience shame spikes before anything has gone wrong. Situations involving evaluation, feedback, uncertainty, or rest activate the same prediction system.

Trigger pattern: most situations where failure is predicted (i.e., imaginal), not necessarily occurring, activate shame and internal threat.

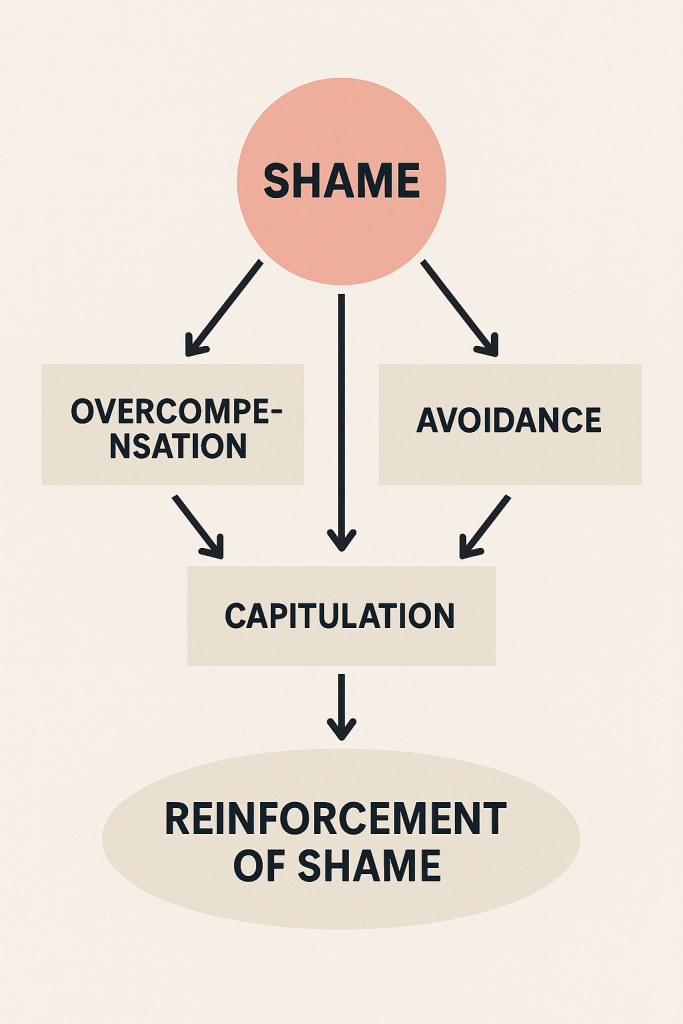

The Pendulum-Effect: how shame maintains distress

NA-CBT® uses the Pendulum-Effect formulation to map how clients attempt to manage shame. Three poles typically emerge:

- Overcompensation:

Perfectionism, overworking, people-pleasing, hyper-preparation, harsh self-criticism as “motivation”. - Capitulation:

Low mood, hopelessness, self-loathing, “What’s the point?”, giving up. - Avoidance:

Social or professional withdrawal, procrastination, numbing behaviours, reassurance-seeking, distraction, emotional withdrawal.

Although these strategies look different, they share the same function: protecting against the felt experience of shame. Over time, however, they reinforce it.

Physiological vulnerabilities—poor sleep, low movement, metabolic instability—often increase the amplitude of the pendulum, making swings more intense and harder to interrupt. This is where TED becomes clinically central.

The TED Self-Check

A 30-second reset you can use anytime emotions start to spike

When you feel anxious, irritable, flat, overwhelmed, or stuck in self-criticism, pause. Before analysing yourself or the situation, gently run through these steps—without judgement.

1. What hurts right now — and where?

What is the actual pain signal in this moment?

Name the felt experience, not the story:

- tight chest

- heat in the face

- drop in the stomach

- lump in the throat

This separates raw affect from interpretation.

2. Is this emotional reaction warranted, unwarranted, or warranted to a degree?

Given the situation, does this intensity fit the facts—or is threat being amplified?

You are not asking “Is this emotion bad?”

You are asking “Is my nervous system accurately calibrated right now?”

Example:

- Event: My boss says the presentation needs more work.

- Interpretation: “This is terrible. I can’t tolerate this. I’m being shamed.”

- Affect: Sharp shame spike, threat response.

- Warrant check:

- Some discomfort is warranted (feedback can sting).

- The intensity of shame is only partly warranted.

- A shame underlayer is amplifying the reaction.

This step creates psychological space without invalidating emotion.

3. TED check: what might be fuelling the spike?

T — Tiredness

How rested am I right now?

E — Exercise

How much have I moved today?

D — Diet

How steady is my energy and nourishment?

When the body is steadier, emotional calibration improves, and meaning-making becomes fairer!

Behavioural experiments and exposure work (with physiological support)

In NA-CBT®, exposure is framed as updating predictions, not forcing fear away.

For shame-based threat systems, exposure often involves:

- allowing imperfection,

- tolerating feedback without immediate self-attack,

- staying present while shame sensations rise and fall.

TED is crucial here. When physiology is unstable, exposure can feel overwhelming or retraumatising. When the system is steadier through regular exercise, improved diet and sleep, clients can remain succesfully within the window of tolerance, allowing corrective learning to occur.

Behavioural experiments might include:

- submitting work that is “good enough,”

- asking a question without over-preparing,

- delaying reassurance-seeking,

- allowing small mistakes without immediate repair.

Each experiment tests the old prediction: “If I’m not perfect, I’ll be shamed or rejected.”

Shame and self-loathing repair

Because shame is the core affect, NA-CBT® does not rely on cognitive restructuring alone. Repair occurs across multiple levels:

- Affective: staying with bodily shame sensations without collapse or attack

- Narrative: identifying internalised parental voices and shame-based meanings

- Relational: experiencing being seen without humiliation

- Physiological: reducing baseline threat sensitivity through TED

Over time, clients develop a non-shaming internal regulator—an Integrated Self capable of noticing shame without obeying it.

Relapse prevention and self-regulation planning

Relapse prevention in NA-CBT® focuses on recognising early signs of pendulum acceleration, not eliminating emotion.

Clients learn to notice:

- rising perfectionism or avoidance,

- faster shame activation,

- disrupted sleep, reduced movement, irregular eating.

Here, the TED self-check becomes a long-term inner compass. Returning to TED (i.e., the fundamentals – better sleep, exercise, better diet) during periods of stress often prevents full relapse by stabilising physiology before old affective loops take over.

Setbacks are reframed as signals, not failures: “My nervous system is under strain; what support does it need right now?”

Conclusion

Within NeuroAffective-CBT®, lifestyle regulation, affective formulation, exposure, and identity repair are not separate tracks. They are interlocking components of a single system aimed at recalibrating threat, softening shame dominance, and restoring psychological flexibility. TED does not replace depth work, in fact it makes deeper work possible. As such, the TED and Pendulum-Effect formulation modules in particular, can be used in conjunction with any school of psychotherapy, as illustrated in the case examples above. They offer a transdiagnostic framework for understanding how physiology, affect, and behaviour interact to maintain or reduce psychological distress.

NA-CBT®, is not necessarily a short-term protocol but a lifelong self-regulation compass. When emotions surge, clients are encouraged to return to three simple questions:

- How tired am I?

- How much have I moved?

- How steady is my nourishment?

By repeatedly stabilising physiology first, clients gain greater freedom in how they think, feel, and act—supporting deeper emotional regulation, reduced shame, and more integrated identity over time.

Medical and Nutritional Disclaimer

The information on this page is provided for educational and therapeutic context only and is not intended as medical, nutritional, or prescribing advice. NeuroAffective-CBT® practitioners do not diagnose medical conditions or prescribe supplements outside of a comprehensive assessment and only if individual core profession allows it. As such, any discussion of nutrition, micronutrients, or lifestyle factors is offered as part of a psychological assessmnet formulation and should not replace consultation with a qualified medical professional. Clients are encouraged to discuss supplements, medications, and health concerns with their GP or relevant healthcare provider.