Daniel Mirea (October 2025)

NeuroAffective-CBT® | https://neuroaffectivecbt.com

Abstract

In this seventh instalment of the TED (Tired–Exercise–Diet) Series, we explore the neuroscience of physical exercise and its central role in emotional regulation, cognitive function, and mental health.

Within the NeuroAffective-CBT® (NA-CBT®) framework, exercise represents the “E” in TED – the second pillar of biological stability upon which self-regulation and psychological flexibility depend.

This chapter presents both theoretical foundations and clinically applicable guidance for integrating physical and relaxation training, circadian rhythm alignment, and behavioural activation into therapeutic practice.

Drawing from sports science, neuroendocrinology, and behavioural neuroscience, it outlines evidence-based applications for enhancing biological resilience and emotional regulation.

Ultimately, this instalment concludes the biological foundations of the TED model, offering clinicians a cohesive framework for embedding exercise-related interventions into the NeuroAffective-CBT therapeutic process.

A glossary of key terms is provided at the end of the article to support comprehension and deepen the reader’s learning experience.

Introducing TED within the NA-CBT Framework

The TED model (Tired–Exercise–Diet) integrates neuroscience, psychophysiology, and behavioural science into a cohesive structure for promoting emotional regulation and biological stability. Within NeuroAffective-CBT, TED forms the foundation of the Body–Brain–Affect Triangle, a conceptual model linking physiology, cognition, and emotion (Mirea, 2023; Mirea, 2025).

Earlier instalments in this series examined six primary regulators of mood and cognition:

• Creatine (Part I)

• Insulin Resistance (Part II)

• Omega-3 Fatty Acids (Part III)

• Magnesium (Part IV)

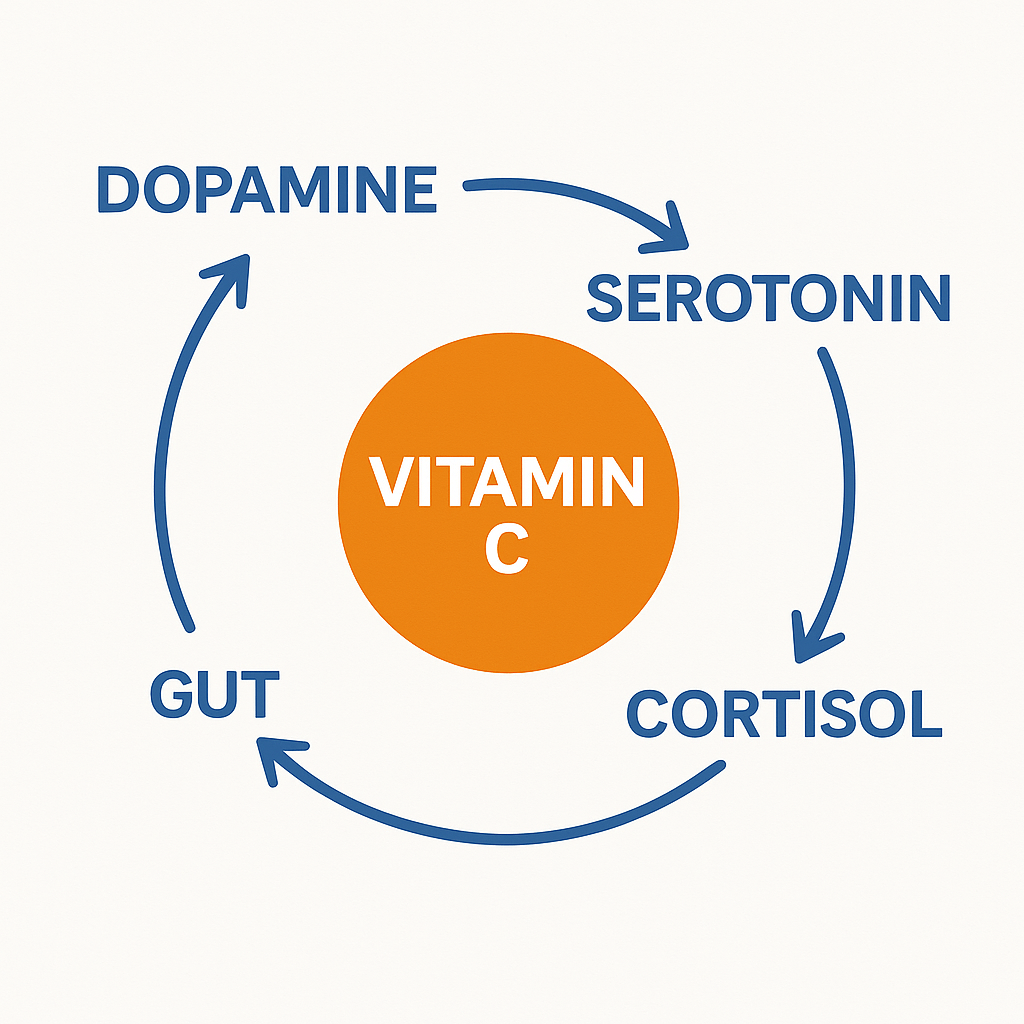

• Vitamin C (Part V)

• Sleep (Part VI) – the neurobiology of fatigue and recovery within the Tired pillar

This chapter extends the model to the “Exercise” component, the dynamic driver of both physical and psychological resilience, while revisiting the “Tired” pillar through the lens of sleep neuroscience and affect regulation to underscore their interdependence within NeuroAffective-CBT.

The “E” – Exercise as the Biological Catalyst

“E” stands for Exercise: a symbol of physical strengthening and a reminder that movement is integral to human adaptability and emotional balance. Evidence consistently demonstrates that regular physical activity not only supports immune function but also regulates hormones, enhances protein synthesis (in parallel with sleep-related recovery), and contributes to the management and prevention of a wide range of mental health conditions (Nieman, 2018; Mahindru, 2023; Mennitti et al., 2024; Strasser, 2015; Deslandes, 2014).

Clinically, it is difficult to separate the “T” (sleep and fatigue regulation) from the “E” (exercise) or the “D” (diet): each pillar continuously shapes and constrains the others. The final instalment of this series (Part VIII: “Diet”) will explore the relationship between muscle mass and glucose regulation, providing further evidence that muscle-strengthening activity exerts measurable effects on both body and mind. This relationship is deeply evolutionary. Humans were not designed for sedentary living or sugar-rich diets, but for movement, exploration, and endurance, capacities that supported survival, innovation, and psychological adaptability. Conversely, insufficient sleep or impaired recovery (Part VI: “Sleep Training”) can significantly disrupt these processes. One could reasonably argue that the survival and regulation of both brain and body depend on the coordinated foundations of sleep, physical activity, and appropriate nutrition (including both eating and hydration).

When it comes to strength and movement, the focus of this article, regular exercise has the unique capacity to restore synchrony between body, brain, and affect. Exercise is not ancillary to personal coaching or therapy; it is a biological stabiliser and an emotional educator.

Strength Training as Brain and Resilience Training

When exercise is discussed within the NeuroAffective-CBT framework, it is not viewed merely as fitness training or muscular conditioning. It is understood as a structured way of training the nervous system and actively supporting brain health, emotional regulation, and resilience.

Exercise is best conceptualised as a process of biological adaptation, rather than a single workout or technique. Across multiple lines of research, one finding is consistent: resistance training does not only strengthen the body; when applied deliberately and progressively, it produces meaningful and measurable effects in the brain as well.

There is frequent debate about whether individuals should lift heavy or light weights. From a muscular perspective, both approaches can stimulate hypertrophy depending on volume, intensity, and individual response. However, when the focus shifts to neurocognitive and resilience-related outcomes, the evidence points to a different organising principle. For neurocognitive and resilience outcomes, the more reliable driver is progressive effort and consistency (rather than a single rep range).

To generate robust brain-related effects, resistance training must be sufficiently challenging to require focused effort, coordination, and controlled exertion. In practical terms, this means lifting loads that feel demanding yet manageable, requiring attention, intention, and engagement rather than mechanical repetition alone. This type of effort sends a powerful afferent signal from the body to the brain.

When muscles contract under meaningful load, they release a range of signalling molecules known as myokines, which act as messengers between peripheral tissues and the central nervous system. These signals influence brain metabolism, synaptic plasticity, and stress adaptation. Importantly, several myokines that promote inflammation during illness or chronic stress exert anti-inflammatory and regulatory effects when released in the context of exercise, illustrating the context-dependent nature of these biological signals (Pedersen, 2007; Petersen and Pedersen, 2005; Gleeson et al., 2011). In other words, the same signalling molecules can either amplify stress and inflammation or support regulation and recovery, depending on when and why they are released. Exercise shifts the biological message from one of threat to one of adaptation.

These muscle-derived signals support learning, memory formation, and adaptive stress responses, particularly in brain regions involved in emotional regulation. One such region, the hippocampus, plays a critical role in memory, mood regulation, and stress modulation. It is well established that hippocampal volume and function can decline with ageing, chronic stress, and depressive illness. Encouragingly, structured exercise interventions have been shown to support hippocampal volume, neurogenesis, and memory performance, even later in life (Erickson et al., 2011).

Exercise also stimulates the release of growth-supporting substances within the brain, most notably brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF supports synaptic plasticity, learning capacity, and emotional regulation, and is often reduced in states of chronic stress, depression, and cognitive decline. Both aerobic and resistance-based exercise have been shown to increase BDNF availability, particularly when training is regular and sufficiently effortful (Wrann et al., 2013; Szuhany, Bugatti and Otto, 2015). This means that it is the regular exposure to meaningful effort, rather than any single exercise modality, that appears most critical for supporting neuroplasticity and emotional regulation.

Beyond neuroplasticity, regular exercise plays a key role in regulating systemic and neuroinflammation, a process increasingly implicated in mood disorders, cognitive impairment, and stress-related conditions. Exercise-induced myokine signalling helps shift the immune system toward a more balanced, anti-inflammatory profile, supporting mental clarity, emotional stability, and long-term brain health (Petersen and Pedersen, 2005; Gleeson et al., 2011).

From a NeuroAffective-CBT perspective, these findings reinforce a central principle of the TED model: exercise is not optional or secondary to psychological work. It functions as a biological stabiliser and an emotional educator. Through repeated cycles of effort, recovery, and adaptation, the body teaches the brain how to regulate arousal, tolerate stress, and recover effectively. In this way, physical strengthening becomes a powerful medium through which resilience, flexibility, and emotional regulation are biologically trained.

Exercise, Adaptation, and Individualisation

To sustain motivation and promote long-term adherence, physical strengthening programmes should always be individualised, taking into account differences in age, sex, current physical condition, as well as personal preferences and cultural values.

Research consistently shows that when physical activity is enjoyable and personally meaningful, when it connects to an individual’s goals, such as improved strength, confidence, or self-image, both physical and psychological outcomes are significantly enhanced. A foundational paper in Self-Determination Theory by Deci and Ryan (2000) demonstrated that intrinsic motivation – the sense of enjoyment, personal meaning, and autonomy, predicts adherence and well-being across multiple domains, including physical activity, while a comprehensive review by Teixeira et al. (2012) further confirmed that autonomous motivation and enjoyment are key predictors of both exercise adherence and psychological benefit.

Within the NeuroAffective-CBT framework, exercise recommendations integrate both muscle activation (tensing or strengthening) and muscle relaxation practices. What contracts must also release – this natural cycle of tension and relaxation supports recovery, balance, and emotional regulation.

This principle is exemplified in Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR), first introduced by Edmund Jacobson in the 1930s (Jacobson, 1938). PMR combines focused attention with abdominal breathing, guiding individuals through cycles of tensing and releasing specific muscle groups. Over time, this practice develops interoceptive awareness – the ability to sense and modulate bodily tension, recognise signs of stress, and release it through mindful breathing. More recent research shows that enhancing interoceptive awareness can also improve attentional control, focus, learning capacity, and ultimately cognitive flexibility, key components of adaptive emotional regulation and psychological resilience (Farb, Segal and Anderson, 2013; Schulz, 2016).

- Martial arts training supports individuals struggling with confidence, assertiveness, or low self-esteem, blending controlled power with discipline and focus.

- Team sports are often beneficial for those with social anxiety, providing gradual social exposure within structured, cooperative settings.

- Yoga: effective for stress regulation and interoceptive awareness, with added benefits for mobility and strength depending on style (e.g., Hatha/Iyengar for alignment and control; Vinyasa/Ashtanga for conditioning). Can be prescribed on its own or as an adjunct to any of the above. Consider trauma-sensitive formats when relevant; introduce load and range progressively, and use care with generalised hypermobility (prioritise stability and pain-free ranges).

- Culturally rooted movement practices, such as Capoeira in Brazil, Tai Chi in East Asia, or traditional dance forms found in many Indigenous and Mediterranean cultures, can serve as powerful, identity-affirming exercises. These activities not only promote physical health but also reinforce cultural belonging, foster feelings of acceptance, and build community connection. Such practices can be particularly beneficial for individuals experiencing social isolation or depression, as they combine movement, rhythm, and shared meaning — all of which strengthen emotional resilience and a sense of self within a social context (Koch et al., 2019; Li et al., 2012).

- For clients with Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD), bodybuilding requires careful framing and monitoring; appearance-driven goals can reinforce maladaptive self-evaluation, whereas performance-based strength training may be safer.

Modern therapeutic approaches such as Grounding, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (Kabat-Zinn, 2003), or Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (Segal, Williams, and Teasdale, 2002) share this same purpose: enhancing body awareness, recalibrating neurophysiological responses, and strengthening emotional self-regulation.

Ideally, when physical health permits, one should train daily, alternating between activation (strength or resistance training) and relaxation (PMR, Grounding or Mindfulness) to maintain both physical tone and emotional equilibrium.

TED Takeaway:

• Pair strength with release (PMR/yoga/mindfulness) to preserve the physiological rhythm of activation–recovery.

• Practical cadence (health permitting): train most days, alternating activation (20–40 min) and relaxation (10–20 min) to maintain tone and equilibrium.

• Enjoyment and meaning are not optional; they are mechanisms of adherence and benefit.

Condition-Specific Exercise: Matching Movement to Mind

Certain exercise modalities align particularly well with specific emotional or cognitive profiles, provided they are introduced with gradual exposure and incremental goals that promote both physical and psychological growth.

Therapeutic exercise selection should always remain person-centred, attuned to both psychological needs and affective drivers of behaviour, while respecting individual and cultural identity.

TED Takeaway:

• Match the modality to the mechanism you want to train (confidence, social approach, cultural belonging, stress regulation).

• Keep exposure graded and goals process-focused; adjust style and dose to the person.

NA-CBT Tools for Performance Priming

- Breathing, Attention & Arousal Regulation:

Your breathing pattern is one of the fastest ways to change how alert, focused, or calm your body feels, it’s a direct link between the body, brain, and emotions. In simple terms, how you breathe sends a signal to your nervous system about whether it’s time to perform or recover.

When you need to up-regulate, that is, increase alertness, focus, and readiness before a challenging effort, try short, sharp inhales or slightly constrained exhales.

This kind of breathing activates your body’s sympathetic nervous system (the “get up and go” system), increasing blood flow, oxygen delivery, and mental sharpness.

For example:

• Before a sprint, lift, or high-intensity set, take two or three quick inhales through the nose and one strong exhale through the mouth.

• You’ll feel your heart rate rise and your focus sharpen, your body preparing to perform.

Then, between sets or after the workout, you want to down-regulate, to shift into recovery mode. This is when you lengthen your exhales or practise relaxation methods such as Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR) or breathing and stretching. Long, slow breaths stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system, your “rest and repair” mode, lowering heart rate, easing muscle tension, and improving focus for the next round.

In essence, your breath acts like a volume dial for your nervous system:

• Faster or shallower breathing turns up the system for performance.

• Slower, deeper breathing turns it down for recovery and calm.

Learning to consciously move between these two physiological states – activation and recovery – strengthens both performance and resilience. These principles align closely with findings in applied sport psychology, where self-regulation of attention and arousal is central to maintaining consistent, high-level performance (Weinberg and Gould, 2019).

Over time, this skill becomes a cornerstone of self-regulation training within the NeuroAffective-CBT® framework, linking movement, breath, and attention into one coherent system for emotional and physical balance.

2. High-Signal Tools: Music, Caffeine, and Nootropics

Tools such as caffeine, motivational music, and certain cognitive enhancers (nootropics) can temporarily increase energy, drive, and attentional sharpness before training. Used thoughtfully, they may support performance, reduce perceived effort, and help clients initiate exercise when motivation is low.

However, the nervous system adapts quickly to high-intensity signals. When these aids become routine (used in every session), their effects often diminish, and training can start to feel “impossible” without them. Over time, reliance on external stimulation may displace the development of intrinsic focus, self-efficacy, and self-regulation, the very capacities the TED framework aims to strengthen.

These are adjuncts, not therapeutic interventions. They should be used strategically, not as a primary method for emotional regulation or behavioural activation.

A practical guideline is to reserve high-signal tools for key sessions (e.g., heavy strength days, high-intensity training, or days when engagement is unusually difficult), while keeping most workouts low-signal so that attention, drive, and consistency are trained internally.

This aligns with a signal-to-noise principle: when stimulation is constant, the brain begins to filter it out; when it is occasional, it remains meaningful and effective.

Clinical caution: Caffeine and stimulant-like compounds can exacerbate anxiety, insomnia, panic symptoms, irritability, or cardiovascular strain in vulnerable individuals. A common evidence-informed range for caffeine is ~1–3 mg/kg, avoiding late-day intake to protect sleep. Always consider contraindications and interactions (e.g., anxiety disorders, hypertension, pregnancy, and psychotropic medication use), and err on the side of conservative dosing.

TED Takeaway: Use high-signal tools sparingly to preserve their potency and to protect the deeper therapeutic goal, building resilient, self-generated regulation rather than dependence on stimulation.

3. Boundaries that Prime Intent and Focus

Setting a physical or mental threshold before training, such as drawing a line on the floor, standing at the gym door, or taking a moment before stepping onto a platform, can significantly improve performance. This small ritual tells the brain, “I’m about to begin something important“.

Crossing that boundary only when mentally ready acts like a psychological switch, heightening attention, intention, and effort quality. It helps athletes transition from everyday distraction into a state of focused readiness, where the body and mind align for optimal performance.

In practice, this is less about superstition and more about neuro-behavioural priming, conditioning the brain to associate a specific action (crossing the line) with focus and engagement. Over time, this can strengthen self-regulation and consistency, even on low-motivation days.

TED Takeaway:

• Faster, shallower breathing → performance state.

• Slower, longer-exhale breathing → recovery state.

• Save high-signal tools for important sessions to preserve their potency and your intrinsic drive.

• A brief pre-set boundary ritual improves consistency and effort quality.

Body Temperature & Performance

The body’s ability to maintain an optimal temperature range influences far more than endurance — it also affects motivation, muscle efficiency, and mental focus.

A lesser-known but fascinating fact is that glabrous skin – the hairless, thick skin found on the palms, soles, and parts of the face (such as the lips and nasal area) – plays a key role in thermoregulation. These regions are rich in arteriovenous anastomoses (AVAs), specialised blood vessels that allow rapid heat exchange. This is why the hands, feet, and face are particularly effective for cooling or warming the body.

This understanding may also shed light on certain ancestral behaviours, such as the instinctive human tendency to touch natural surfaces or another person’s skin to gauge warmth, comfort, or safety, an evolutionary remnant of how we once regulated both physical and emotional connection through touch.

Research shows that palmar cooling (cooling the hands between sets or during endurance exercise) can substantially increase work output in hot conditions, while reducing thermal fatigue and improving recovery (Grahn, Cao & Heller, 2005; Heller, 2010).

Interestingly, Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), a third-wave CBT approach developed by Marsha Linehan, also uses temperature-based interventions for emotional regulation. During states of high emotional arousal, clients are taught to cool the body rapidly using ice packs on the face or brief facial immersion in cold water. This activates the mammalian dive reflex, which lowers heart rate and stimulates the parasympathetic nervous system, producing a powerful calming effect (Linehan, 2014).

When the body overheats, muscles work less efficiently, excessive heat disrupts energy production. As temperature rises, the chemical reactions that generate energy through adenosine triphosphate (ATP) begin to falter. A key enzyme in this process, pyruvate kinase, which helps convert fuel into usable energy, slows down or even stops functioning properly. The result is simple: overheated muscles fatigue faster, lose power, and overall performance declines.

Conversely, controlled cooling helps sustain endurance and recovery by maintaining thermal balance. The palms, soles, and face act as natural radiators through their AVAs, enabling rapid heat dissipation and stabilising core temperature.

Simple practical methods include holding cool (not ice-cold) objects or briefly immersing the hands or feet in cool water between training bouts. This straightforward approach can lower perceived effort, extend training capacity, and accelerate post-exercise recovery.

These findings reinforce the importance of temperature regulation as part of recovery and emotional self-regulation within the TED framework.

TED Takeaway:

• Gentle cooling after exercise helps the body shift more quickly into recovery mode by supporting the parasympathetic nervous system, which governs rest, repair, and relaxation.

• Rinsing the hands, feet, or face with cool water after exercise stabilises heart rate and calms the body within 30–60 minutes, improving recovery and emotional balance.

• Excessive or immediate full-body cold exposure — such as jumping straight into an ice bath — can interfere with the body’s mTOR repair signalling, slowing muscle growth and adaptation.

• In short: a little cooling helps the body recover faster, but too much too soon can blunt the benefits of training.

• Safety note: Cold immersion should be avoided in cases of unmanaged cardiovascular disease, severe Raynaud’s, or neuropathy; seek medical guidance if unsure.

Cortisol isn’t the enemy: time it, don’t flatten it

Because cortisol often rises during stress or anxiety, it’s sometimes misunderstood as purely harmful. In reality, short-term cortisol spikes after training are vital, they mobilise fuel, drive adaptation, and signal recovery.

The goal is rhythmic spikes that return to baseline, not chronic elevation.

Blunting cortisol too early, through overuse of supplements, anti-inflammatories, or excessive carbohydrates, can impair muscle repair. Instead, allow cortisol to rise during exertion and fall gradually post-training. Strategically timed carbohydrate intake can facilitate this recovery phase by naturally lowering cortisol while replenishing glycogen stores and improving sleep quality.

Heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV) help monitor stress–recovery balance. Low HRV or chronically elevated HR may signal overtraining, poor sleep, or psychological stress. Moderate, consistent exercise combined with rest, hydration, and mindfulness restores autonomic balance and resilience.

TED Takeaway:

• Evening or post-training carbohydrates (prefer minimally processed, starchy sources) can assist cortisol down-shifting, support sleep, and replenish glycogen.

• Avoid overuse of “cortisol blockers” – heavy alcohol, or sedative strategies, as they can impair adaptation and sleep architecture.

Mirrors, Interoception, and Motor-learning

Technological aids such as mirrors or video feedback can be useful in the early stages of learning new movements. They help individuals understand form and alignment, but the ultimate goal is a felt sense of movement, awareness that comes from within, rather than dependence on external feedback.

Hypertrophy focus (muscle growth and strengthening): Using a mirror occasionally or posing between sets can improve body awareness and help engage the target muscles more effectively during training.

Speed or skill learning (e.g., Olympic lifts, sprints): Avoid mirrors, as they shift attention outward and reduce interoceptive awareness, the ability to sense and adjust body position and movement internally.

TED Takeaway:

• Mirrors and video feedback can support early learning, but lasting skill comes from internal awareness.

• Develop a felt sense of movement – coordination and control without reliance on external cues.

Train Recovery and Relaxation: The Pathway to Physiological Resilience

Like any other skill, the ability to switch off, relax, and recover can be trained. Recovery is not fixed, it can be strengthened over time. Just as you build muscle through progressive challenge, you can train your recovery systems by occasionally pushing slightly beyond what feels comfortable (in a safe and controlled way). Each small, well-managed challenge helps your body and mind learn to adapt to stress more effectively.

To build this kind of resilience, focus on the fundamentals:

- Keep your sleep regular. Get morning light to wake your system and dim evening light to prepare for rest.

- Eat well. Make sure you’re getting enough energy, protein, and hydration to help your body repair itself.

- Use temperature wisely. Short, gentle exposures to heat or cold (with enough rest between) train your body to adapt to different environments.

- Stay connected and mindful. Supportive relationships, journaling, mindfulness, or relaxation exercises such as Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR) all help keep your nervous system flexible and balanced.

This rhythmic cycle of effort and restoration forms the biological basis of resilience within the TED framework, teaching the body to recover as deliberately as it performs.

TED Takeaway:

• Use graded, manageable challenges to expand capacity — always with control and recovery.

• In NeuroAffective-CBT, this reflects a core principle: gradual, intentional exposure to small challenges increases the ability to cope with stress while maintaining emotional balance and self-regulation.

Conclusion

Exercise is more than physical conditioning; it is a biological and emotional regulator – a living interface between movement, emotion, and cognition. Behavioural principles long recognised this: Lewinsohn’s model linked reduced engagement with loss of reinforcement; Behavioural Activation (Jacobson, Martell & Dimidjian, 2001) reinstated purposeful activity; Beck’s cognitive therapy integrated behavioural experiments, graded tasks and activity scheduling (Beck et al., 1979).

Within the NeuroAffective-CBT model, the “E” in TED symbolises this central truth: emotional stability and cognitive clarity arise not in isolation, but through the synchrony of body and mind.

The TED framework demonstrates that emotional regulation is not achieved through thought alone, but through the rhythmic cooperation of the body’s systems, when we are tired, exercised, and nourished in balance. In essence, exercise functions both as a biological stabiliser and an emotional educator, a continuous dialogue between movement, mood, and meaning.

The TED model reminds us that resilience is not a fixed trait but a rhythm, cultivated through synchrony, when the body rests, moves, and restores itself in harmony.

In the forthcoming and final section, “D”, we will complete the TED model by exploring Diet, the biochemical cornerstone of mental health, and its interdependent relationship with exercise, sleep, and emotional regulation.

Ten TED Takeaways: Physical Exercise and Mental Health

- Movement is Medicine. Exercise is a biological necessity that supports immunity, hormone balance, protein synthesis, and emotional regulation.

- Cortisol is adaptive, not destructive. It should rise during exertion and fall during recovery.

- Evolution Favouring Motion. Human physiology is designed for activity. Movement restores the natural synchrony between body, brain, and affect.

- Balance Between Tension and Release. Strength must coexist with recovery. PMR, yoga, and mindfulness sustain this physiological rhythm.

- Exercise as Emotional Education. Physical training teaches the body–mind connection, transforming tension into awareness and control.

- Personalised Movement and Training. Match the type or exercise modality to the person: martial arts for confidence, team sports for social anxiety; use caution with appearance-driven training in BDD.

- Embodied Self-Regulation. Within NeuroAffective-CBT®, exercise is the “E”, the biological catalyst linking movement with mood and self-regulation.

- Use “high-signal” tools sparingly. Keep caffeine, music, and stimulants for key days to maintain their effect.

- Intentional boundaries prime the mind. Physical thresholds before training enhance focus and effort quality.

- Integration, Not Isolation. Emotional stability requires synergy between Tired, Exercise, and Diet – rest, movement, and nourishment.

TED Exercise Prescription

Exercise as Exposure, Adaptation, and Nervous-System Training

Purpose (NA-CBT® lens)

Within NeuroAffective-CBT, exercise is prescribed not primarily for fitness, aesthetics, or performance optimisation, but as a structured biological intervention that trains the nervous system, supports brain plasticity, and strengthens emotional regulation through repeated cycles of effort and recovery.

This prescription translates the neurobiological principles outlined above, including myokine signalling, neuroplastic adaptation, hippocampal support, and inflammation regulation, into a clinically safe, psychologically informed framework for practice.

Exercise is therefore used simultaneously as:

- a graded exposure to physiological activation,

- a behavioural activation tool,

- and a trainer of autonomic flexibility and recovery capacity.

1. Core Principle: Controlled Stress + Deliberate Recovery

Exercise is prescribed as intentional, repeatable exposure to manageable physiological stress, followed by explicit recovery, rather than exhaustion, punishment, or aesthetic optimisation.

In NA-CBT terms:

- Activation = sympathetic engagement (effort, mobilisation, focus, signalling)

- Recovery = parasympathetic engagement (release, integration, repair)

Resilience does not emerge from remaining in either state, but from learning to move fluidly between them. This movement between activation and recovery is the biological mechanism through which exercise supports brain health and emotional regulation.

2. Behavioural Activation Through Consistent Effort

For clients experiencing depression, anhedonia, avoidance, or motivational collapse, the primary therapeutic target is consistency, not intensity.

Prescription principles:

- Prioritise regular completion over maximal effort

- Begin with doses that are reliably achievable

- Frame exercise as engagement rather than performance

Recommended dose (health permitting, under specialist advice only):

- 20–40 minutes of resistance or compound movement

- ~5–10 sets per major muscle group per week (maintenance → improvement range)

- Loads that feel challenging but controllable (≈30–70% perceived effort)

Clinical rationale:

Repeated exposure to effort that is survivable, predictable, and followed by recovery restores agency, reward prediction, and forward momentum — the core mechanisms of behavioural activation and resilience training.

3. Exercise as Graded Exposure to Sensation and Arousal

Resistance training naturally exposes clients to:

- increased heart rate

- muscular discomfort

- breathlessness

- effort-related frustration

Therapeutic framing:

“We are teaching your nervous system that activation is safe, temporary, and recoverable.”

Guidelines:

- Increase load, volume, or complexity gradually

- Avoid constant training to failure

- Use process-focused goals (“complete the set”, “maintain form”)

Exposure principle:

Physiological stress is dosed, time-limited, and followed by recovery, allowing adaptive signalling (rather than threat learning) to occur.

4. Trauma-Sensitive Modifications (Essential)

For clients with trauma histories, panic disorder, dissociation, or high baseline arousal, the priority is predictability and control.

Key adaptations:

- Avoid surprise intensity or abrupt escalation

- Avoid prolonged breath-holding or extreme exertion early on

- Avoid coercive, appearance-driven, or competitive language

Practical modifications:

- Shorter sets, longer rests

- Emphasis on choice, pacing, and exit options

- Grounding cues (foot contact, orienting, slow exhales)

- End every session with explicit down-regulation

Key rule:

No session should end with unresolved physiological activation.

5. Autonomic Regulation: Train the Exit, Not Just the Effort

The recovery phase is not optional — it is where learning consolidates.

Mandatory recovery phase (5–10 minutes):

- Long-exhale breathing

- Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR)

- Gentle stretching or stillness

- Non-Sleep Deep Rest (NSDR)

Clinical goal:

To teach the nervous system how to actively disengage from activation, reinforcing parasympathetic access as a transferable emotional regulation skill.

6. Monitoring Readiness and Adaptation (Optional)

Where appropriate, clients may be guided to monitor:

- subjective energy and motivation

- perceived effort and recovery quality

- CO₂ tolerance / slow-exhale capacity

NA-CBT principle:

Improved interoceptive awareness enhances self-regulation, prevents overexposure, and supports adaptive pacing.

7. Frequency and Rhythm (Health Permitting)

Ideal rhythm:

- Most days: some form of movement

- Alternate activation-focused days with recovery-focused days

- Pair resistance training with relaxation practices

TED’s rule of thumb:

If activation goes up, recovery must follow.

TED Clinical Takeaway

- Exercise functions as embodied exposure

- Progressive effort and consistency drive brain adaptation

- Recovery trains autonomic regulation

- Resilience emerges from rhythmic stress–release cycles

Within NeuroAffective-CBT, exercise is both a biological stabiliser and an emotional educator, translating effort into regulation, and movement into meaning.

References

Biddle, S.J.H. and Asare, M. (2011) ‘Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: a review of reviews’, British Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(11), pp. 886–895.

Blumenthal, J.A. et al. (2012) ‘Exercise and mental health: integrating behavioural medicine into clinical psychology’, Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, pp. 545–576.

Deci, E.L. and Ryan, R.M. (2000) ‘The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behaviour’, Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), pp. 227–268.

Deslandes, A.C. (2014) ‘Exercise and mental health: What did we learn?’, Frontiers in Psychiatry, 5, Article 66.

Erickson, K.I., Voss, M.W., Prakash, R.S., Basak, C., Szabo, A., Chaddock, L., Kim, J.S., Heo, S., Alves, H., White, S.M., Wojcicki, T.R., Mailey, E., Vieira, V.J., Martin, S.A., Pence, B.D., Woods, J.A., McAuley, E. and Kramer, A.F. (2011) ‘Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(7), pp. 3017–3022. doi:10.1073/pnas.1015950108.

Farb, N.A.S., Segal, Z.V. and Anderson, A.K. (2013) ‘Mindfulness meditation training alters cortical representations of interoceptive attention’, Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(1), pp. 15–26.

Galpin, A.J., Raue, U., Jemiolo, B., Trappe, T.A., Harber, M.P. and Minchev, K. (2012) ‘Human skeletal muscle fiber type specific protein content’, Analytical Biochemistry, 425(2), pp. 175–182. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2012.03.018.

Gleeson, M., Bishop, N.C., Stensel, D.J., Lindley, M.R., Mastana, S.S. and Nimmo, M.A. (2011) ‘The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease’, Nature Reviews Immunology, 11, pp. 607–615.

Grahn, D.A., Cao, V.H. and Heller, H.C. (2005) ‘Heat extraction through the palm of one hand improves aerobic exercise endurance in a hot environment’, Journal of Applied Physiology, 99(3), pp. 972–978.

Heller, H.C. (2010) ‘The physiology of heat exchange: glabrous skin and performance enhancement’, Stanford University Human Performance Laboratory White Paper, Stanford, CA.

Jacobson, E. (1938) Progressive Relaxation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003) ‘Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future’, Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), pp. 144–156.

Koch, S.C., Riege, R.F., Tisborn, K., Biondo, J., Martin, L. and Beelmann, A. (2019) ‘Effects of dance movement therapy and dance on health-related psychological outcomes: A meta-analysis update’, Frontiers in Psychology, 10, Article 1806.

Li, F., Harmer, P., Fitzgerald, K. and Eckstrom, E. (2012) ‘Tai Chi and postural stability in patients with Parkinson’s disease’, New England Journal of Medicine, 366(6), pp. 511–519.

Linehan, M.M. (2014) DBT Skills Training Manual. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press.

Mahindru, A. (2023) ‘Role of Physical Activity on Mental Health and Well-Being’, Frontiers in Psychiatry, Article 9902068.

Mennitti, C., Che-Nordin, N., Meah, M.R., Poole, J.G. and González-Alonso, J. (2024) ‘How Does Physical Activity Modulate Hormone Responses?’, Biomolecules, 14(11), p. 1418.

Mirea, D. (2023) NeuroAffective-CBT®: ‘Tired, Exercise and Diet Your Way Out of Trouble: TED is Your Best Friend!’ NeuroAffective-CBT®. Available at: https://neuroaffectivecbt.com/2023/07/18/teds-your-best-friend/ (Accessed: 30 October 2025).

Mirea, D. (2025) NeuroAffective-CBT®: Advancing the Frontiers of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy. London: NeuroAffective-CBT® (Accessed: 30 October 2025).

Nieman, D.C. (2018) ‘The compelling link between physical activity and the body’s defence system’, British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(13), pp. 789–790.

Pedersen, B.K. (2007) ‘Role of myokines in exercise and metabolism’, Journal of Applied Physiology, 103(3), pp. 1093–1098. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00080.2007.

Petersen, A.M.W. and Pedersen, B.K. (2005) ‘The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise’, Journal of Applied Physiology, 98(4), pp. 1154–1162. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00164.2004.

Ratey, J.J. and Loehr, J.E. (2011) ‘The positive impact of physical activity on cognition and brain function’, Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 23(4), pp. 373–394.

Salmon, P. (2001) ‘Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: a unifying theory’, Clinical Psychology Review, 21(1), pp. 33–61.

Schulz, S.M. (2016) ‘Neural correlates of heart-focused interoception: implications for neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation’, Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Article 1119.

Segal, Z.V., Williams, J.M.G. and Teasdale, J.D. (2002) Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression: A New Approach to Preventing Relapse. New York: Guilford Press.

Stonerock, G.L., Hoffman, B.M., Smith, P.J. and Blumenthal, J.A. (2015) ‘Exercise as treatment for anxiety: systematic review and analysis’, Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 49(4), pp. 542–556.

Strasser, B. (2015) ‘Role of physical activity and diet on mood, behaviour, and cognition’, Neuroscience & Biobehavioural Reviews, 57, pp. 107–123.

Szuhany, K.L., Bugatti, M. and Otto, M.W. (2015) ‘A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor’, Journal of Psychiatric Research, 60, pp. 56–64. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.10.003.

Teixeira, P.J., Carraça, E.V., Markland, D., Silva, M.N. and Ryan, R.M. (2012) ‘Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: a systematic review’, International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9, Article 78.

Weinberg, R.S. and Gould, D. (2019) Foundations of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 8th edn. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

World Health Organization (2020) Physical Activity Factsheet: Mental Health Benefits of Exercise. Geneva: WHO.

Wrann, C.D., White, J.P., Salogiannnis, J., Laznik-Bogoslavski, D., Wu, J., Ma, D., Lin, J.D., Greenberg, M.E. and Spiegelman, B.M. (2013) ‘Exercise induces hippocampal BDNF through a PGC-1α/FNDC5 pathway’, Cell Metabolism, 18(5), pp. 649–659. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2013.09.008.

Further Reading & Clinical Resources

NeuroAffective-CBT® Framework:

• Mirea, D. (2025) NeuroAffective-CBT®: NeuroAffective-CBT®: Advancing the Frontiers of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy. London: NeuroAffective-CBT® [Accessed 30/10/2025].

• Official website: https://neuroaffectivecbt.com

Exercise and Mental Health:

• Weinberg, R.S. and Gould, D. (2019) Foundations of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 8th edn. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

• World Health Organization (2020) Physical Activity Factsheet: Mental Health Benefits of Exercise. Geneva: WHO.

• Harvard Medical School (2021) The Exercise Effect: How Physical Activity Boosts Mood and Mental Health. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Health Publishing.

• Ratey, J.J. (2008) Spark: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain. New York: Little, Brown and Company.

Relaxation and Mindfulness Practices:

• Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013) Full Catastrophe Living. New York: Bantam.

• Jacobson, E. (1938) Progressive Relaxation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Therapeutic Integration:

• Beck, J.S. (2021) Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

• Linehan, M.M. (2015) DBT® Skills Training Manual. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press.

• Davis, M., Eshelman, E.R. and McKay, M. (2019) The Relaxation and Stress Reduction Workbook. 7th edn. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Glossary and Key Terms:

Behavioural activation is a CBT approach that helps people improve their mood by reconnecting with meaningful, goal-directed activities, especially when they feel low or unmotivated. When someone is depressed or anxious, they often withdraw from daily life and lose motivation, which makes them feel even worse. Behavioural activation works by re-introducing positive routines, encouraging gradual re-engagement in small, rewarding, or purposeful actions such as exercise, social contact, or creative tasks. In the TED framework, behavioural activation supports both the “Exercise” and “Diet” pillars by re-energising the body, increasing motivation, and helping to rebuild emotional stability through movement and engagement.

Circadian Rhythm

Your circadian rhythm is the body’s natural 24-hour internal clock that controls when you feel awake, sleepy, and even how your mood, hormones, and energy levels change throughout the day. It’s regulated mainly by light and darkness, sunlight in the morning tells your brain it’s time to be alert, while darkness at night signals that it’s time to rest. Keeping this rhythm regular (for example, by getting morning light, avoiding late-night screens, and sleeping at consistent times) helps improve sleep quality, mood, focus, and recovery.

Cognitive Corollary

A related mental or thinking process that accompanies a physical or biological change. For example, a cooler body temperature can make effort feel easier, improving focus and learning.

Cortisol

A natural hormone released by the adrenal glands, often called the “stress hormone.” It helps regulate metabolism, inflammation, and the body’s response to stress. Healthy cortisol levels rise in the morning to energise you and drop in the evening to help you rest.

HR (Heart Rate)

The number of times your heart beats per minute. Resting heart rate tends to be lower in fitter individuals and can rise with stress, dehydration, or illness.

HRV (Heart Rate Variability). A measure of the small variations in time between heartbeats. High HRV usually means your body can adapt well to stress; low HRV can indicate fatigue, overtraining, or poor recovery.

Hypertrophy Stimuli

Anything that triggers muscles to grow larger and stronger, such as resistance training, mechanical tension, or specific metabolic stress during exercise.

mTOR Repair Pathway

Short for “mechanistic Target of Rapamycin”, mTOR is a key biological pathway that helps the body grow and repair cells, especially muscle tissue. After exercise, this pathway acts like a “construction manager”, signalling the body to build new proteins, repair tiny muscle tears, and grow stronger tissue. If this process is interrupted for example, by too much cold exposure immediately after training, muscle recovery and growth can slow down.

Myokines

Myokines are helpful chemicals released by your muscles when you move. They act like messages sent from your muscles to your brain and the rest of your body. These messages can improve mood, reduce stress, support brain health, and help the body recover. When released through regular exercise, myokines help the body feel calmer, stronger, and more balanced.

Neuropathy

Damage or dysfunction of the nerves, often causing tingling, numbness, weakness, or pain, most commonly in the hands and feet. It can result from diabetes, injury, infections, or certain medications.

NSAIDs (Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs)

A class of medications, such as ibuprofen, naproxen, and aspirin, used to reduce pain, inflammation, and fever. Overuse can sometimes irritate the stomach or affect kidney (renal) and liver (hepatic) function.

Protein synthesis – body’s process of building new proteins, which are essential for repairing tissues, producing hormones, and supporting growth and recovery, particularly after exercise. It’s how your muscles rebuild and strengthen following physical activity, and it also plays a role in brain health, helping support learning, memory, and mood regulation. This process depends on good nutrition, regular exercise, and adequate sleep, all of which are central to the TED model.

In essence, protein synthesis is the body’s repair and renewal system, keeping both mind and body in balance.

Raynaud’s / Vascular Disorders / Neuropathy

Conditions that alter blood flow or nerve function – consider when prescribing temperature strategies. Raynaud’s is a condition where blood vessels in the fingers and toes become overly sensitive to cold or stress, causing them to temporarily narrow. This limits blood flow and can make the skin turn white or blue and feel numb or painful.

Renal / Hepatic

“Renal” refers to the kidneys, which filter waste and maintain fluid balance. “Hepatic” refers to the liver, which processes nutrients, hormones, and drugs. Both organs are vital for detoxification and energy metabolism.

Tolerance – refers to the body’s process of adapting to a substance or stimulus over time, which makes its effects weaker or shorter-lasting.

For example, if someone regularly uses caffeine, certain medications, or motivational tools (like loud music or pre-workout stimulants), the body and brain gradually become less responsive to them. This means that more of the same stimulus is needed to achieve the same effect, or it stops working altogether.

In the context of the TED model, tolerance explains why “high-signal” tools, such as caffeine, nootropics, or intense motivation strategies, should be used sparingly, to prevent over-reliance and maintain natural motivation and balance.