Dr Marco Cortez (UKCP, MBACP)

Abstract

This case report describes the application of NeuroAffective-CBT® (NA-CBT®) with a single working mother, Susan, presenting with chronic stress, shame-organised self-criticism, affective instability, and fluctuating anxiety and low mood. The article may be relevant for clinicians working with clients who ‘understand their patterns’ cognitively but struggle to sustain regulation under stress.

Although Susan demonstrated motivation and cognitive insight consistent with traditional CBT, therapeutic progress was initially constrained by physiological dysregulation and entrenched affective patterns. NA-CBT was therefore selected for its neurobiologically informed, transdiagnostic framework (Mirea, 2018). Central to the intervention were the Pendulum-Effect formulation and the TED (Tired–Exercise–Diet) module, which supported affect regulation and consolidation of learning. Outcomes indicate improvements in emotional stability, behavioural consistency, and self-compassion. The case highlights both the clinical utility and the limitations of NA-CBT within a time-limited therapeutic context characterised by ongoing psychosocial stress.

This case offers a clinically grounded illustration of how an affect-regulation-first, transdiagnostic approach may be applied to chronic stress and burnout-adjacent presentations, where cognitive insight is present but sustained behavioural change is constrained by physiological and shame-organised responding.

Keywords: NeuroAffective-CBT; affect regulation; shame; behavioural experiments; Pendulum Effect; TED model; psychological flexibility; embodied cognition; transdiagnostic psychotherapy; lifestyle interventions; affective neuroscience; case study

Introduction

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is an established evidence-based treatment for anxiety and depressive disorders (Beck, 1976; Hofmann et al., 2012). However, CBT may be less effective for clients whose difficulties are dominated by chronic shame, affective dysregulation, and embodied stress responses, rather than by explicit cognitive distortions alone (Gilbert, 2010; Panksepp, 2011).

NeuroAffective-CBT extends traditional CBT by explicitly integrating findings from affective neuroscience, attachment theory, and psychophysiology (Mirea, 2018). NA-CBT proposes that durable cognitive and behavioural change depends on the regulation of subcortical affective systems and bodily states, particularly in individuals experiencing persistent emotional volatility and shame-organised responding (Mirea, 2018; Schore, 2012).

This paper presents a detailed, practice-based case study illustrating the application of NA-CBT with a single working mother whose presenting difficulties were coherently conceptualised using the Pendulum-Effect formulation. As a single-case report, the aim is not to necessarily establish efficacy but rather to provide a clinically grounded illustration of how affect-regulation-focused interventions may support therapeutic engagement and change in complex, non-diagnostic presentations.

Client Information

The client, referred to as Susan, is a 42-year-old single mother of two children, one of whom has significant additional needs. She works part-time in a professional role and experiences ongoing financial strain, chronic fatigue, and emotional overwhelm. Susan self-referred for therapy due to persistent anxiety, low mood, bodily tension, and difficulty initiating and sustaining work-related tasks.

She reported no previous experience of psychological therapy and denied suicidal ideation or risk to others. Her difficulties were longstanding and had intensified in the context of prolonged caregiving demands and occupational disruption. Although Susan did not meet formal criteria for occupational burnout, her presentation reflected core burnout features including emotional exhaustion, reduced task initiation, and shame-organised overcompensation.

Presenting Difficulties

Susan reported the following difficulties:

- persistent tiredness and bodily pain

- anxiety related to finances and perceived competence

- fluctuating mood states rather than sustained depression

- strong self-criticism and pervasive shame

- cycles of overworking followed by avoidance and emotional shutdown

Despite insight into her thinking patterns, Susan struggled to implement consistent behavioural change. Emotional reactions were often rapid, intense, and disproportionate to present-day triggers, suggesting affective processes operating beneath conscious cognition and outside deliberate control (LeDoux, 1996; Mirea, 2025).

Rationale for NeuroAffective-CBT®

Although Susan met many criteria for standard CBT suitability (Safran et al., 1993), her difficulties were better explained by affective and physiological dysregulation rather than faulty beliefs alone or a discrete diagnostic category. Instead, her presentation reflected a cluster of symptoms common across common mental health presentations, organised around shame-dominant affective responding and chronic stress exposure.

NA-CBT was therefore selected to:

- Address emotional reactivity at a neuroaffective level

- Reduce shame-organised responding

- Stabilise physiological states that interfered with learning

- Support belief change through emotionally salient experience

When affective systems are chronically activated, cognitive techniques may inadvertently intensify self-criticism or compensatory over-effort (Mirea, 2018). This pattern was observed during the early phase of Susan’s therapy, further supporting the need for a regulation-first approach.

Pendulum-Effect Formulation

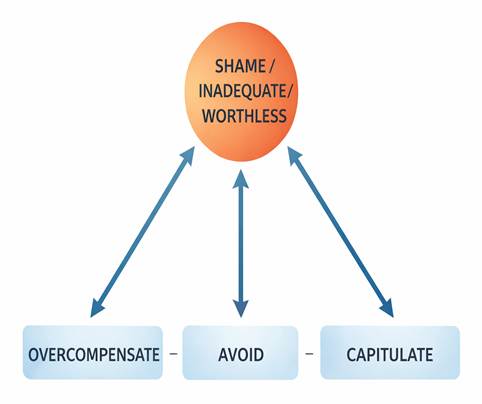

A core feature of NA-CBT is the Pendulum-Effect formulation, which conceptualises psychological distress as oscillation between opposing coping strategies driven by unresolved core affect (Mirea, 2018). These oscillations occur largely outside conscious awareness and function to maintain dominant affects such as shame, guilt, fear, or self-criticism.

In Susan’s case, this oscillation was pronounced. She alternated between procrastination (intentional delay) and avoidance (withdrawal) until tasks became unavoidable. These phases were then followed by periods of overcompensation marked by excessive responsibility-taking, urgency, and perfectionistic standards. Such efforts were typically unsustainable and culminated in collapse, accompanied by intensified self-blame, hopelessness, and emotional withdrawal (or capitulation). A similar pendulum pattern was observed in her eating behaviour, in which episodes of overeating (overcompensation) were followed by periods of restriction (avoidance) and harsh self-reproach (capitulation), further reinforcing shame and loss of self-trust.

Within the Pendulum-Effect formulation, these patterns reflect the complex and dynamic oscillation between avoidant, overcompensatory, and capitulating strategies rather than a linear sequence of behaviours. Shame-based core affect was conceptualised as occupying the functional centre of the system, with oscillating strategies serving as complex self-sabotage, to temporarily manage distress while simultaneously reinforcing negative self-evaluative beliefs such as “I am inadequate” or “I am failing.” Importantly, these strategies were understood not as pathology, but as historically adaptive survival responses shaped by cumulative relational, developmental, and contextual stress (Mirea, 2018; Porges, 2011).

Therapeutic work therefore focused on reducing the amplitude of oscillation rather than eliminating emotional experience, while gradually introducing adaptive coping strategies aligned with authentic personal values that promote psychological health and functional independence. Intervention emphasised affect regulation, increased awareness of pendulum dynamics, and the cultivation of compassionate choice at moments of activation, thereby supporting greater stability and flexibility in emotional and behavioural responding.

Pendulum Poles Identified

Susan oscillated between the following coping poles:

- Overcompensation: excessive responsibility, perfectionism, overworking

- Avoidance: procrastination, emotional numbing, withdrawal

- Capitulation: resignation, hopelessness, self-blame

Conceptually, this can be represented as:

These responses were understood not as pathology, but as adaptive survival strategies shaped by past and current relational stress (Mirea, 2018; Porges, 2011). An early narrative contributing to Susan’s internalised shame involved comparison with an idealised maternal figure perceived as coping effortlessly, reinforcing beliefs of inadequacy and shame-based self-evaluation.

Therapeutic work focused on reducing pendulum amplitude by strengthening affect regulation, increasing awareness of oscillation patterns, and cultivating compassionate choice, rather than attempting to eliminate emotional experience altogether.

Description of the NA-CBT® Intervention

Module 1: Engagement and Affective Assessment

Assessment emphasised collaborative formulation, mapping Susan’s pendulum patterns, and identifying bodily markers associated with distinct affective states. Emotional responses were normalised as nervous-system reactions shaped by experience and rooted in the brain’s predictive regulatory processes, whose primary function is to maintain physiological survival. This framing supported affect tolerance and therapeutic engagement (Schore, 2012; Mirea, 2018).

Within NA-CBT–informed practice, early sessions are understood as a critical opportunity to establish safety, trust, and a robust therapeutic alliance oriented toward authentic living rather than a life organised around internalised shame states. During this phase, the therapist’s role involves providing guidance and psychoeducation alongside compassion and active listening, thereby supporting engagement while modelling a regulated, responsive, and relationally attuned stance.

Module 2: Psychoeducation

NA-CBT® can appear to be a phased treatment; however, clinical practice demonstrates that modules are applied flexibly and intersect dynamically according to formulation and regulatory needs (Mirea, 2018). Psychoeducation was therefore embedded throughout therapy rather than delivered as a discrete phase.

This approach is consistent with evidence that learning and meaning-making enhance neuroplasticity and psychological flexibility, now recognised as a transdiagnostic protective factor (Kolb, 1984; Davidson and McEwen, 2012; Kashdan and Rottenberg, 2010).

Susan was introduced to:

• the role of pendulum-effect oscillating strategies in reinforcing shame

• distinctions between core affect and cognitive appraisal

• the regulatory function of emotions such as shame (signalling perceived social threat and guiding protective behaviour)

• the impact of physiological stress on emotional intensity

• the role of lifestyle stability in moderating affective reactivity

This psychoeducation reduced self-blame and strengthened engagement, consistent with NA-CBT®’s emphasis on emotional literacy (Mirea, 2018).

Module 3: TED – Tired, Exercise, Diet

The TED module was implemented as a foundational affect-regulation strategy rather than as adjunctive lifestyle advice (Mirea, 2023; Mirea, 2025). Within NA-CBT–informed practice, TED targets background physiological instability known to amplify emotional reactivity and undermine cognitive and behavioural learning (Damasio, 1999).

Behavioural changes and corresponding behavioural experiments were introduced across all three TED domains. Within the Tired domain, interventions prioritised sleep regularity and pacing rather than sleep optimisation. Within the Exercise domain, distinctions were made between incidental activity and intentional regulating movement such as yoga or purposeful walking, which were more consistently associated with reductions in affective volatility. Within the Diet domain, psychoeducation addressed the short-term stimulating and longer-term destabilising effects of high sugar intake, reframing reliance on sugar as a stress-driven coping strategy rather than a sustainable energy source.

Susan observed that spikes in self-criticism and shame reliably followed prolonged sedentary days characterised by binge eating and alcohol use. Within the Pendulum-Effect formulation, these patterns were understood as oscillations between overcompensation, avoidance, and capitulation, functioning as a recurring self-reinforcing cycle driven by unresolved shame-based affect.

In response, brief “exercise snacks” were introduced not as fitness goals, but as identity-repair behaviours (e.g., “I am someone who cares for my body and nervous system”).

Susan also noted heightened fear and emotional reactivity following poor sleep, skipped meals, and excessive caffeine intake. Using the TED self-check, these affective shifts were re-contextualised as substantially physiological rather than as evidence of personal failure. This reframing reduced shame and overwhelm, allowing subsequent exposure-based and cognitive interventions to proceed with greater tolerance and engagement.

Where relevant, Susan was encouraged to seek medical or dietetic input to support nutritional adequacy and metabolic stability, consistent with TED’s positioning as complementary to, rather than a replacement for, healthcare input (Mirea, 2025). Following consultation with her general practitioner, routine blood investigations identified physiological factors (e.g., iron and vitamin D insufficiency) considered contributory to fatigue and fluctuating energy levels. Addressing these factors further supported affect regulation and behavioural engagement within therapy without displacing psychological intervention.

As emphasised by Mirea (2025), within NA-CBT informed practice, lifestyle regulation, affective formulation, exposure, and identity repair are conceptualised as interlocking components of a single regulatory system rather than as parallel or competing therapeutic tracks.

Module 4: The Integrated Self

Within NA-CBT, this phase of therapy focuses on working with specific, emotionally salient (“hot”) memories that activate cascades of negative affect and self-defeating behavioural responses. Attending to discrete memory fragments is often more effective than attempting to process broad or global relational narratives, which may become cognitively assimilated over time into fear, guilt or shame-based conclusions that are resistant to change (Erten MM, 2018; Mirea, 2018).

Clients were supported to maintain present-moment physiological awareness while narrating specific memories in a contained and titrated manner. This process enabled the gradual re-appraisal of trauma-linked affect as tolerable bodily sensation rather than overwhelming threat. Over time, emotional fluctuations were experienced as manageable variations in internal state, supporting acceptance and the integration of a more adaptive and cohesive sense of self (Gilbert, 2010; Mirea, 2018).

Module 5: Coping Skills-Enhanced Behavioural Experiments

Although behavioural experiments are described as a discrete module within NA-CBT, the creation of new lived experience is emphasised throughout therapy, reflecting the model’s use of intersecting and flexible modules rather than a linear sequence (Mirea, 2018). Behavioural experimentation was therefore conceptualised as an ongoing learning process supporting affect regulation, belief revision, and identity repair.

Across therapy, experiments were designed to test emotional predictions alongside cognitions, consistent with experiential learning theory (Kolb, 1984; Engelkamp, 1998) and the principle that belief change occurs primarily through emotionally meaningful action (Chadwick, Birchwood and Trower, 1996).

Module 6: Consolidation and Ending

Ending focused on recognising early pendulum swings, applying TED independently, and maintaining ongoing affect awareness. Relapse prevention was framed as a process of continued regulation rather than symptom elimination (Mirea, 2018). TED was positioned as a long-term inner compass, with setbacks reframed as signals of nervous-system strain rather than personal failure.

Outcomes

Therapy progressed steadily across 18 sessions. The initial six sessions focused on assessment, collaborative formulation, psychoeducation, and the introduction of the TED framework, with particular emphasis on affect regulation and lifestyle stabilisation.

The subsequent nine sessions facilitated early narrative processing and the development of acceptance through self-compassion. These sessions also incorporated behavioural and social experiments aimed at promoting new learning, strengthening adaptive coping, and gradually modifying overcompensatory, avoidant, and capitulating coping strategies. Such patterns were frequently organised around shame-based conditional assumptions, for example: “If I do not sacrifice myself and meet others’ demands perfectly, I am worthless,” accompanied by implicit affective experiences of shame and guilt.

The final three sessions were conducted on a monthly basis and focused on consolidating therapeutic gains, strengthening relapse-prevention strategies, and supporting the client’s increasing capacity for autonomous self-regulation.

By the end of therapy, Susan demonstrated:

- Adoption of a more regulated lifestyle informed by TED principles

- Reduced affective volatility and improved emotional self-regulation

- Increased tolerance of uncertainty and distress

- Greater behavioural consistency across work and caregiving contexts

- Development of a more compassionate and flexible self-narrative

Although significant external stressors persisted, Susan experienced emotional responses with greater awareness, reduced escalation, and increased capacity for regulation, indicating meaningful consolidation of therapeutic learning.

Symptomatic progress was monitored using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and CORE-32, administered at assessment, session nine, and session eighteen. Improvements were observed across key domains of concern, including chronic stress, day-to-day functioning, shame-organised self-criticism, affective instability, anxiety, and low mood.

Learning Outcomes

This case demonstrates that:

- “Affect regulation may be a prerequisite for sustained cognitive and behavioural change.”

- “The Pendulum-Effect formulation offers a dynamic, non-pathologising framework for understanding oscillating coping patterns.”

- “TED-based interventions can function as core therapeutic tools rather than adjunctive lifestyle advice.”

- “Behavioural experiments are most effective when designed to be emotionally salient.”

- “NA-CBT may be particularly well suited to presentations characterised by chronic stress, low self-esteem, and shame-organised responding.”

Critical Evaluation

Strengths

- Integrates affective neuroscience, lifestyle regulation, and principles from nutritional psychiatry within an evidence-based CBT framework

- Reduces self-blame through the normalisation of physiological and affective processes

- Provides a coherent and non-pathologising framework for complex, non-diagnostic presentations

Limitations

- Requires advanced therapist skill in affective attunement and regulation

- Requires additional therapist knowledge drawn from domains that traditionally fall outside the core remit of psychotherapy, including nutrition, neuroscience, and exercise psychology

- Some concepts may initially feel abstract or unfamiliar to clients

- Time-limited therapy constrained the depth of narrative integration and longer-term consolidation

Clinical Reflexivity

With hindsight, earlier emphasis on TED-based stabilisation may have reduced initial pendulum oscillations more rapidly. Encouraging liaison with primary healthcare services, including general practitioner consultation and routine blood investigations, provided clinically useful contextual information that complemented psychological formulation and supported affect regulation.

This early physiological stabilisation facilitated increased engagement in self-care and self-compassion practices, which in turn enabled deeper therapeutic work with shame-laden narratives, including beliefs linking personal worth to constant performance and self-sacrifice.

Agenda management required ongoing sensitivity to balance therapeutic structure with respect for the client’s lived complexity, ensuring that therapeutic direction did not inadvertently replicate earlier experiences of invalidation or over-demand.

Conclusion

This case illustrates how NeuroAffective-CBT can extend traditional CBT by directly engaging the affective and physiological processes that organise psychological distress. Through the combined use of the Pendulum-Effect formulation and TED (Tired–Exercise–Diet), NA-CBT supported sustainable emotional and behavioural change within the context of ongoing psychosocial stress. Rather than functioning solely as a time-limited intervention, NA-CBT may be understood as a lifelong self-regulation framework, offering clients a practical internal compass for stabilising physiology first and thereby expanding freedom in how they think, feel, and act.

More broadly, this case reflects a growing movement within psychotherapy toward a deeper integration of mind and body. As neuroscience, psychosomatic medicine, nutritional psychiatry, and biologically informed treatments increasingly converge, it is becoming difficult to justify approaches that address cognition and emotion in isolation from physiology. Integrative models such as NA-CBT are well positioned to contribute to this evolving landscape by offering clinicians a coherent framework that bridges affective neuroscience with everyday therapeutic practice (Mirea, 2025).

NA-CBT® positions itself not merely as a set of techniques, but as a compassion-centred, neurobiologically informed psychological approach. While many traditional psychotherapeutic schools have historically approached lifestyle factors with caution, emerging evidence and clinical experience suggest that disrupted sleep, nutritional instability, and insufficient movement are pervasive across mental health presentations and frequently undermine therapeutic progress. Addressing these factors thoughtfully and collaboratively does not dilute psychological depth; rather, it creates the physiological conditions necessary for insight, emotional processing, and behavioural change to take root.

From this perspective, interventions such as TED are not ancillary to therapy but foundational. Encouraging appropriate medical collaboration when clients present with chronic fatigue or low energy can help identify modifiable physiological contributors that, when addressed, enhance affect regulation, therapeutic engagement, and overall quality of life. Such integration reflects a broader shift away from symptom-focused treatment toward whole-person care, where psychological flexibility, embodied awareness, and compassionate self-regulation become central therapeutic outcomes.

Taken together, this case suggests that the future of psychotherapy may lie less in refining ever more specialised techniques and more in developing integrative, transdiagnostic frameworks capable of holding mind, body, affect, and behaviour within a single coherent model. NA-CBT offers one such framework, grounded in neuroscience, oriented toward compassion, and designed to meet the complex realities of contemporary clinical practice.

Future Directions for Psychotherapy

The evolving landscape of mental health care increasingly calls for psychotherapeutic models that move beyond rigid diagnostic categories and isolated treatment techniques. As research continues to clarify the reciprocal influence of physiology, affect, cognition, and behaviour, future psychotherapy is likely to become more integrative, transdiagnostic, and biologically informed.

Approaches such as NeuroAffective-CBT point toward a future in which affect regulation and nervous-system stability are recognised as foundational prerequisites for psychological change. Rather than positioning lifestyle, embodiment, and self-regulation strategies as peripheral or adjunctive, emerging models are likely to incorporate these elements centrally within formulation and intervention. This shift has the potential to enhance treatment accessibility, durability of outcomes, and client autonomy.

Future developments in psychotherapy may also involve closer collaboration between psychological practitioners and other health disciplines, including primary care, nutritional psychiatry, and psychosomatic medicine. Such interdisciplinary integration may support earlier identification of physiological contributors to emotional distress and reduce unnecessary chronicity across mental health presentations.

Finally, the field may increasingly value therapeutic frameworks that prioritise psychological flexibility, compassion, and embodied self-awareness over symptom suppression alone. In this context, psychotherapy may evolve from a primarily corrective endeavour into a developmental process, one that supports individuals in cultivating sustainable self-regulation, resilience, and a more integrated sense of identity across the lifespan.

Disclaimer

This case study is intended for educational and professional discussion purposes only. It does not constitute clinical guidance, diagnosis, or treatment recommendations. Therapeutic approaches described should be applied only by appropriately trained professionals and adapted to individual client needs. Readers are advised to consult relevant clinical guidelines and professional supervision when translating concepts into practice.

Ethics and Anonymisation Statement

All identifying client information has been altered to protect anonymity. Informed consent was obtained for the use of anonymised clinical material for educational and dissemination purposes.

References

Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York: International Universities Press; 1976.

Chadwick P, Birchwood M, Trower P. Cognitive therapy for delusions, voices and paranoia. Chichester: Wiley; 1996.

Damasio A. The feeling of what happens: body and emotion in the making of consciousness. London: Heinemann; 1999.

Davidson RJ, McEwen BS. Social influences on neuroplasticity: stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nature Neuroscience. 2012;15(5):689–695.

Engelkamp J. Memory for actions. Psychology of Learning and Motivation. 1998;38:1–40.

Erten MM, Williams JM, Raes F, Hermans D. Memory Specificity Training for Depression and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2018;9(1):1432007. PMID: 29355369. doi:10.1080/20008198.2018.1432007.

Gilbert P. Compassion focused therapy. London: Routledge; 2010.

Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJ, Sawyer AT, Fang A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2012;36(5):427–440.

Kashdan TB, Rottenberg J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin Psychology Rev. 2010;30(7):865–878.

Kolb DA. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Prentice Hall; 1984.

LeDoux J. The emotional brain: the mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1996.

Mirea D. The underlayers of NeuroAffective-CBT® [Internet]. NeuroAffective-CBT®; 2018 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. Available from: https://neuroaffectivecbt.com/2018/10/19/the-underlayers-of-neuroaffective-cbt/

Mirea D. Tired, Exercise and Diet your way out of trouble, TED’s your best friend [Internet]. NeuroAffective-CBT®; 2023 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. Available from: https://neuroaffectivecbt.com/2023/07/18/teds-your-best-friend/

Mirea D. The use of lifestyle interventions in psychotherapy [Internet]. NeuroAffective-CBT®; 2025 Dec 17 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. Available from: https://neuroaffectivecbt.com/2025/12/17/the-use-of-lifestyle-interventions-in-psychotherapy/

Mirea D. TED in NeuroAffective-CBT®: an applied self-regulation framework for enhancing emotional well-being through sleep, movement, and nutrition [Internet]. NeuroAffective-CBT®; 2025 Dec 10 [cited 2026 Jan 19]. Available from: https://neuroaffectivecbt.com/2025/12/10/ted-in-neuroaffective-cbt-an-applied-self-regulation-framework-for-enhancing-emotional-well-being-through-sleep-movement-and-nutrition/

Panksepp J. The basic emotional circuits of mammalian brains. Emotion Rev. 2011;3(1):5–14.

Porges SW. The polyvagal theory: neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. New York: W.W. Norton; 2011.

Safran JD, Segal ZV, Vallis TM, Shaw BF, Samstag LW. Assessing patient suitability for cognitive therapy. J Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1993;7(1):11–23.

Schore AN. The science of the art of psychotherapy. New York: W.W. Norton; 2012.