How Early Life Experiences Shape Our Sense of Self

From the moment we are born, our earliest interactions with caregivers begin shaping the lens through which we view ourselves and the world. While overt mistreatment, such as physical punishment, neglect, or abuse, is widely recognised, subtler forms of emotional harm can leave equally lasting psychological imprints. Persistent criticism, emotional invalidation, or unspoken parental expectations may quietly distort a child’s emerging sense of self.

Donald Meichenbaum’s early work on narrative-constructivism (Meichenbaum Free Publications, 2024) offers a powerful framework for understanding how early experiences form the foundation of identity. According to his model, children unconsciously develop internal narratives, or life scripts, based on the emotional messages they receive from caregivers. Behaviourist Daniel Mirea (2018) refers to these internalisations as “narrow lenses” through which we learn to interpret ourselves and our world. These scripts often hinge on perceived conditions for acceptance: “Be perfect,” “Don’t disappoint,” or “Always succeed”. They become internal blueprints for behaviour and identity.

When individuals deviate from these internalised rules, whether intentionally or not, it can evoke intense psychological distress. For instance, someone who grew up believing they must always please others may feel overwhelming shame and guilt when attempting to assert a boundary. Others might experience anxiety or self-sabotage when success feels incompatible with early messages that achievement would lead to rejection or disapproval. In these moments, the distress often doesn’t arise from the external situation itself, but from the unconscious violation of internal survival strategies. Breaking the script can feel like a betrayal of self, evoking shame, guilt, confusion, or resurfaced emotional pain. Therapeutic work that brings these early narratives to light, and helps individuals examine and reframe them, is often essential for healing and for the development of a more authentic, self-compassionate identity.

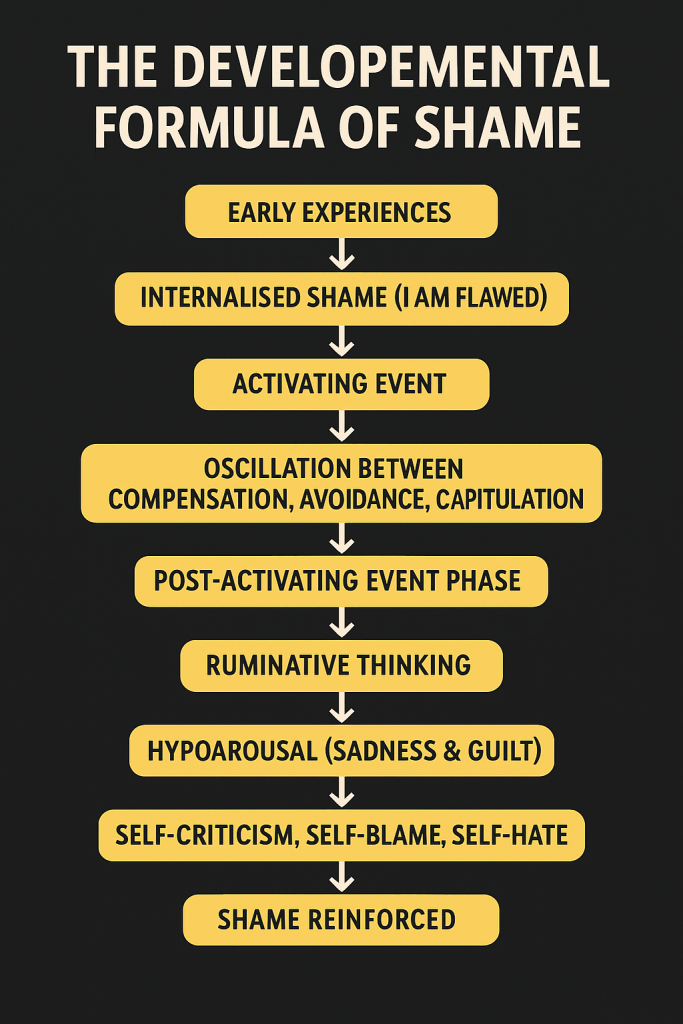

Just as overt mistreatment leaves scars, subtle emotional neglect and persistent invalidation can be just as damaging. Environments that emphasise a child’s flaws while ignoring their strengths, repeating phrases like “You could’ve done better”, or comparing them to siblings or peers, can lead to internalised shame. Over time, such experiences may cultivate what is often referred to as core shame: a deep, embodied sense of being defective, unworthy, or inherently unacceptable (Mirea, 2018). This shame can become embedded within the self-concept, reinforced by experiences of ridicule, teasing, or belittlement.

As children grow, the role of peer relationships becomes increasingly central to their self-esteem. During late childhood and adolescence, physical appearance, popularity, and social belonging rise in importance. Children who feel different, due to body image, skin conditions, or social exclusion, are especially vulnerable to shame-based beliefs such as “I’m ugly”, “I’m weird” or “No one likes me”. These beliefs are often intensified by social media, which promotes narrow, unrealistic standards of attractiveness and worth.

Social identity also plays a critical role. How society views and treats the communities we belong to, our culture, class, or ethnicity, shapes how we come to view ourselves. If one’s cultural group is marginalised or discriminated against, societal messages of inferiority or invisibility can deeply seep into the personal identity, compounding feelings of shame or self-doubt.

Importantly, not all harm stems from overt abuse or criticism. Sometimes it’s the absence of nurturing experiences, affection, praise, encouragement, or emotional presence that causes the most damage. Children with caregivers who are physically present but emotionally disengaged may grow up feeling unloved or unseen. Even when their material needs are met, the emotional void can lead to a persistent sense of being fundamentally flawed. Later in life, comparisons with peers who received emotional warmth can deepen this sense of inadequacy.

Such was the case with James. Throughout his childhood, he endured chronic emotional abuse, marked by relentless criticism, verbal attacks, and public humiliation, most often at the hands of his father during family gatherings or in front of peers. Over time, James internalised the belief that he could never measure up, that he would always fall short of his father’s expectations. To cope, he began to rely heavily on external validation and constant reassurance, grasping for fleeting moments of feeling “good enough”.

This emotional backdrop seeded a chronic sense of internalised shame, a deep “felt-sense” that he was fundamentally flawed. To emotionally survive this environment, James developed a set of coping strategies, what we might call life strategies, to navigate social situations and relationships where he felt undeserving or defective. These strategies helped him appear functional and even successful on the outside, but internally, they were rooted in fear, shame, and emotional self-protection.

Even minor interpersonal situations could trigger his shame. For example, if a university acquaintance asked him for a loan, even someone he barely knew or trusted, James felt unable to say “no,” even when his financial situation was precarious. Embarrassed and afraid of being disliked, he would give away money he couldn’t afford to lose. Despite sensing the relationship was one-sided or exploitative, he was unable to assert his needs.

After such encounters, James would spiral into self-criticism. He would replay the event, berating himself for not setting a boundary. In the days that followed, he felt guilt, sadness, and depression, compounded by the recognition that the money would likely never be returned. These episodes only reinforced his internal narrative of unworthiness and deepened his shame.

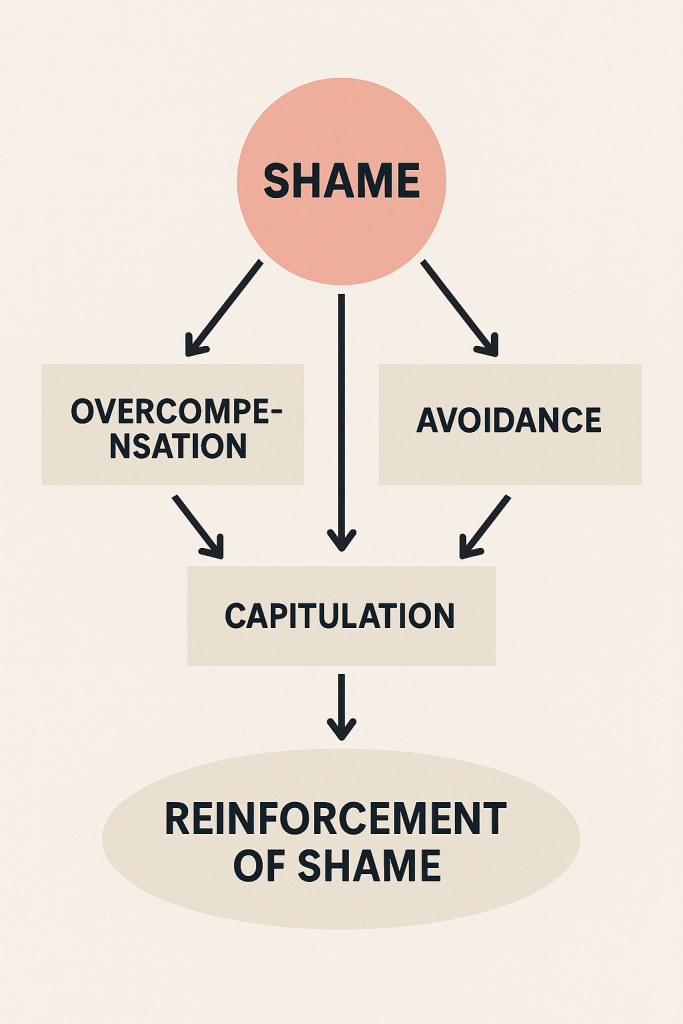

James’s patterns of behaviour reflected three common shame-based coping strategies: overcompensation, avoidance, and capitulation. He would overcompensate by being excessively generous and accommodating, often at the expense of his own wellbeing. He avoided assertiveness and confrontation, fearing rejection. And ultimately, he capitulated, silently accepting that betrayal of his own needs was the price of being liked. “If even my own father didn’t accept me”, he often thought, “why would anyone else?”

Over time, these strategies would become automatic, like an emotional autopilot. Through repeated use, they formed an internalised maintenance program, a hidden operating system, that reinforced his shame and shaped his sense of self across time. What began as a useful defence – a way to survive childhood, ended up as the foundation for chronic low self-esteem and shame, manifesting in symptoms that spanned both anxiety and depression.

Shame as a Core Mechanism

Shame often lies beneath overt symptoms of emotional distress. While clients frequently seek help for anxiety or depression, it is often shame that quietly drives much of their inner turmoil. In this light, chronic low self-esteem may be best understood as a shame-based condition.

Despite its central role, shame is often overlooked in psychotherapy, not out of neglect, but because it tends to remain hidden beneath more visible symptoms that feel immediate to the client. Clients typically tend to present symptoms of anxiety and depression, while the deeper, silent driver, shame, goes unaddressed. Yet neuroaffective research identifies shame as a core emotion, evolutionarily essential for social survival. Without the capacity for shame, early humans would have struggled to understand social hierarchies, maintain group cohesion, or follow communal norms. In this sense, shame originally served an adaptive purpose: to guide behaviour in socially acceptable ways (Matos, Pinto-Gouveia & Duarte, 2013).

Like all other core emotions, shame functions as a sudden “call to action“. It generates immediate internal distress, a state of hyper or hypo-arousal, which demands urgent behavioural regulation. People may respond with submission, withdrawal, compliance, or people-pleasing. These reactions serve as social survival mechanisms, especially for those raised in emotionally unsafe environments.

It is only natural that, when adaptive regulation is lacking, individuals revert to maladaptive strategies like lying, substance use, excessive niceness, or self-betrayal, often learned in childhood through repeated exposure to shame and invalidation.

And so, in a perceived social crisis when emotionally overwhelmed (i.e., activating event), individuals often unconsciously revert to coping mechanisms such as overcompensation, avoidance, or capitulation (i.e., surrendering to shame) in no particular order. These strategies may feel protective in the moment, offering a temporary sense of control or relief. However, they are often subtle forms of self-sabotage and ironically, they end up reinforcing the very shame they were unconsciously trying to manage or escape.

For instance, overcompensation may manifest as perfectionism, over-working to exhaustion, clinging to abusive relationships, giving away money one cannot afford to lose, pretending to like people one inwardly distrusts, or engaging in overly self-sacrificing behaviour, all in a desperate effort to gain acceptance or avoid perceived rejection. These actions may appear altruistic or generous on the surface but are often driven by deep fears of abandonment or worthlessness.

Capitulation occurs when a person begins to behave in ways that conflict with their true self, often to fit in or fulfil internalised narratives of inadequacy. In some cases, this leads to acting out beliefs like: “Since I’m already bad, I might as well be bad and show everyone just how bad I really am”. This distorted logic can result in self-destructive behaviours like compulsive gambling, excessive drinking, drug use, not necessarily driven by desire, but by hopelessness, self-punishment, or a deep yearning to belong. These behaviours serve as powerful, if maladaptive, emotional regulation tools. They may temporarily ease anxiety or internal chaos, but in the long term, they reinforce the painful identity narrative the person is trying to escape: the belief that they are defective, unworthy, or beyond help.

Avoidance strategies may involve a chronic inability to say “no”, withdrawing from social settings, procrastinating, or avoiding interactions that risk judgment or criticism. These behaviours offer immediate emotional relief but are rarely sustainable. Over time, their short-term success becomes neurologically reinforced, because they “worked” once, the brain learns to default to them automatically, even when they are no longer adaptive or helpful.

After the triggering event passes and the individual is left alone and reflective, a second emotional wave often emerges. Long episodes of rumination characterised by intrusive thoughts such as “Why am I like this?”, “I’m useless”, “I always give money I don’t have,” or “No one ever helps me in return” begin to surface. This cascade of self-criticism and self-blame induces a temporary hypo-aroused state of guilt, thus reinforcing the shame cycle.

In this way, individuals can become trapped in recurring emotional loops, cycles of shame, anxiety, guilt, and depression, that are externally triggered, internally reinforced, and sustained by long-standing behavioural and neurobiological patterns. Over time, these behaviours cease to be mere reactions to isolated stressors; they evolve into a default operating system through which the individual interprets and navigates daily life. The underlying core shame remains unexamined, silently shaping emotional responses, relationship dynamics, and everyday decision-making.

Conclusion

Chronic low self-esteem is not merely a collection of negative thoughts or surface-level insecurities, it may be the visible tip of a deeper, shame-based emotional system. Often hidden beneath symptoms of anxiety or depression, shame fuels emotional dysregulation, self-sabotaging behaviours, and entrenched beliefs of unworthiness. Left unexamined, it becomes a silent architect of identity, shaping how one sees themselves, relates to others, and makes daily decisions.

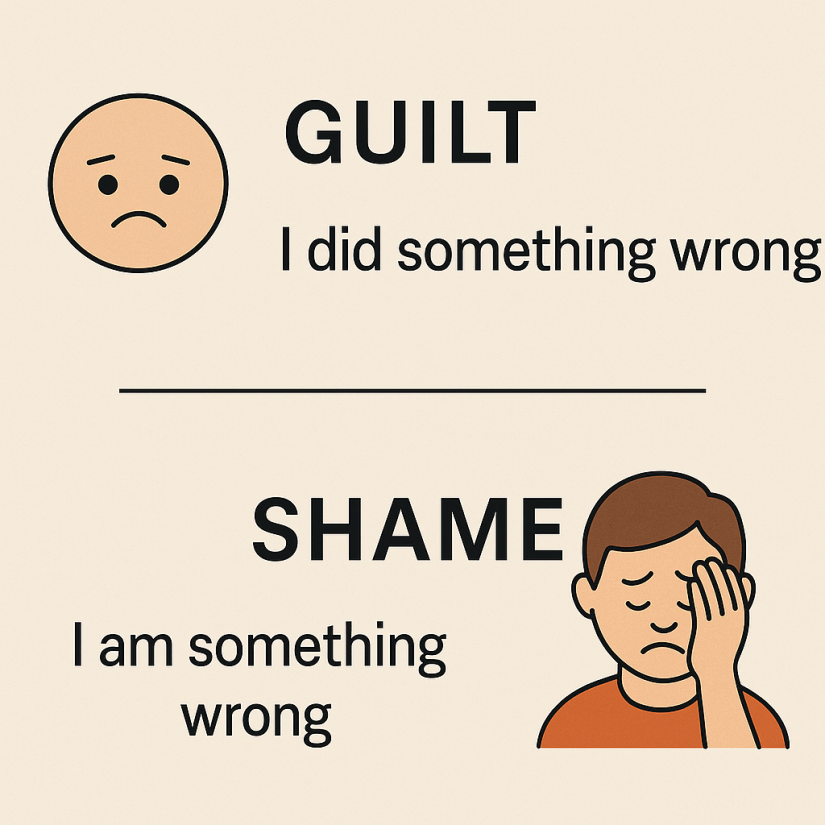

Bringing shame into therapeutic awareness is rarely straightforward, yet it is essential. One of the challenges lies in the confusion that surrounds this complex and often misunderstood emotion. Shame is frequently mistaken for guilt, though the two serve distinct psychological functions. Guilt is behaviour-focused, “I did something wrong”, whereas shame is identity-based, “I am something wrong.” According to the NeuroAffective-CBT developmental model, guilt tends to emerge later in development, while shame takes root earlier, forming a foundational layer of the emotional system.

To loosen shame’s grip, it must be called out and named, explored, and brought into conscious awareness. Only then can individuals begin to interrupt its influence and develop more compassionate, flexible ways of relating to themselves and others.

Crucially, shame should not be demonised. It is part of an adaptive emotional system that evolved over thousands of years, to promote social cohesion and survival. The problem arises when shame becomes chronic and dominant, distorting self-perception, shaping behaviour, and stalling emotional growth. Shame is only painful when it governs the internal world unchecked. The goal in therapy is not to eliminate shame, but to understand its origins, normalise its presence, and dismantle the reinforcing patterns that keep it active.

In doing so, individuals begin to reclaim agency, authenticity, and emotional resilience. Despite its power, shame is not immutable. Through compassionate therapeutic inquiry and reflective self-awareness, people can challenge the narratives that shaped their inner world. By uncovering the roots of shame and gradually rewriting these internal scripts, individuals like James can move from survival toward authenticity, from emotional self-protection to genuine self-acceptance.

Glossary:

Adaptive vs. Maladaptive Behaviours

Adaptive behaviours are healthy coping mechanisms that support resilience, the ability to adapt constructively to difficult or stressful situations. They promote long-term emotional growth and psychological flexibility. In contrast, maladaptive coping mechanisms may offer short-term relief but ultimately reinforce avoidance, overcompensation, or capitulation. These strategies are unproductive and often harmful, preventing individuals from developing more adaptive ways of relating to themselves and others.

Core Emotions

In this article, core emotions (or core affects) are defined as primary emotional systems essential to survival, shared by most mammals. According to neuroaffective research and the work of neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp (2012), these include SEEKING (expectancy/curiosity), FEAR (anxiety), RAGE (anger), LUST (sexual excitement), CARE (nurturance), PANIC/GRIEF (sadness/loss), and PLAY (social joy). Clinical theorist Mirea proposes that SHAME, while derivative of FEAR, also functions as a core affect in humans, distinct yet equally vital for social survival. For example, the behaviour of a shamed or embarrassed dog illustrates how shame functions as a primitive, embodied emotional state.

Deeply-Rooted Beliefs (DRBs)

DRBs first mentioned by Mirea (2018) when describing the fundamentals of NeuroAffective-CBT, refer to early internalised felt-senses accompanied by corresponding beliefs and affective responses. These experiences are typically nonverbal and rooted in emotionally charged moments, often occurring before the individual has the language to articulate them. Originating in childhood, DRBs shape a rigid sense of identity and self-perception. As language develops, these implicit emotional experiences may later be verbalised, often for the first time in adulthood, particularly within a therapeutic setting. DRBs are resistant to change without external support, as individuals frequently dismiss conflicting evidence through cognitive distortions such as mental filtering, a mechanism explored in detail in Mirea’s approach NeuroAffective-CBT.

Felt-Sense / Gut-Sense / Gut-Feelings

These terms are used interchangeably throughout the paper to describe internal sensory experiences that arise in response to perceived threats or rewards. A felt-sense serves as an embodied memory of prior emotional events, functioning as an internal alarm system. It can manifest as a subtle tension, discomfort, or intuitive knowing, guiding decisions and emotional reactions even before conscious thought occurs.

References:

Panksepp, J. & Biven, L. (2012). The Archaeology of Mind: Neuroevolutionary Origins of Human Emotion. W. W. Norton & Company.

Matos, M., Pinto-Gouveia, J. and Duarte, C., 2013. Shame as a functional and adaptive emotion: A biopsychosocial perspective. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 43(3), pp.358-379. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12016

Meichenbaum D (2024). Don Meichenbaum Publications. URL: https://www.donaldmeichenbaum.com/publications (accessed 26.06.2025)

Mirea D (2024). If my gut could talk to me, what would it say? URL: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382218761_If_My_Gut_Could_Talk_To_Me_What_Would_It_Say (accessed 26.06.2025)

Mirea D (2018). The underlayers of NeuroAffective-CBT. URL: https://neuroaffectivecbt.com/2018/10/19/the-underlayers-of-neuroaffective-cbt/ (accessed 26.06.2025)

Edited and supported by: