Daniel Mirea (May 2019)

NeuroAffective-CBT® | https://neuroaffectivecbt.com

Introduction

A brief look at Google Scholar shows that cognitive behavioural therapies (CBT), including so-called “third-wave” approaches such as mindfulness and acceptance-based interventions, are by far the most extensively researched and empirically supported psychological treatments to date. NeuroAffective-CBT (NA-CBT), by contrast, is a much younger cognitive and behavioural therapy. It naturally lags behind in terms of large-scale clinical trials; however, it is a reliable, innovative, transdiagnostic model that has been honed over thousands of hours of supervised and reviewed therapy sessions, which have consistently delivered positive outcomes across a range of client groups. NA-CBT shares its theoretical fundamentals and evidence base with the wider family of cognitive and behavioural therapies, which together constitute the current gold standard in psychiatry and psychological treatment (David, Cristea and Hofmann, 2018; Mirea, 2018).

CBT appears to be the best we currently have, but the field is far from perfect. Precisely because CBT is dynamic and rooted in evidence, gaps in provision are constantly being identified. In response, new and creative solutions are proposed and tested. It is within this evolving context that NA-CBT steps forward to address a specific void. Developed by Daniel Mirea and finely tuned over the last 20 years, NA-CBT was designed to target a growing subclinical population presenting with undiagnosed affective disturbances clustered around shame and self-loathing.

Because the treatment of these phenomena crosses the boundaries of clear diagnostic criteria, the therapeutic approach needs to be both holistic and strategic. NA-CBT therefore relies on a clearly prescribed, modular toolkit aimed at disrupting the mechanisms that predispose, perpetuate, and precipitate shame, self-disgust, low self-esteem, and associated difficulties.

By exploring the underlayers of NA-CBT, this article examines the overlapping mechanisms that underpin a range of cognitive and behavioural methods and summarises the evidence that supports the skills and interventions used in this treatment model.

The assessment stage

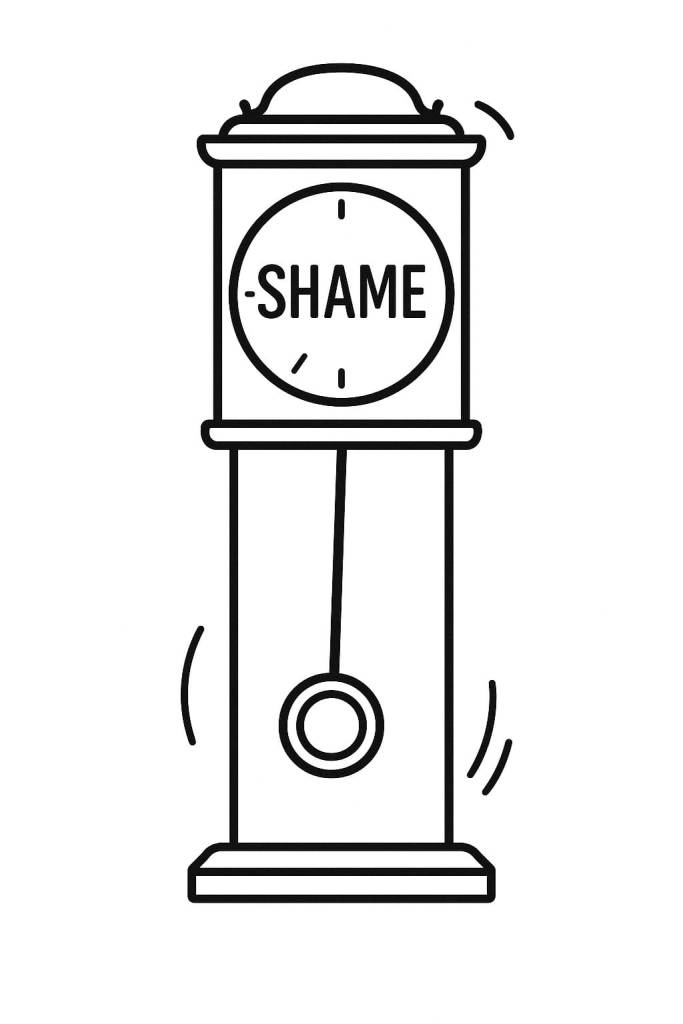

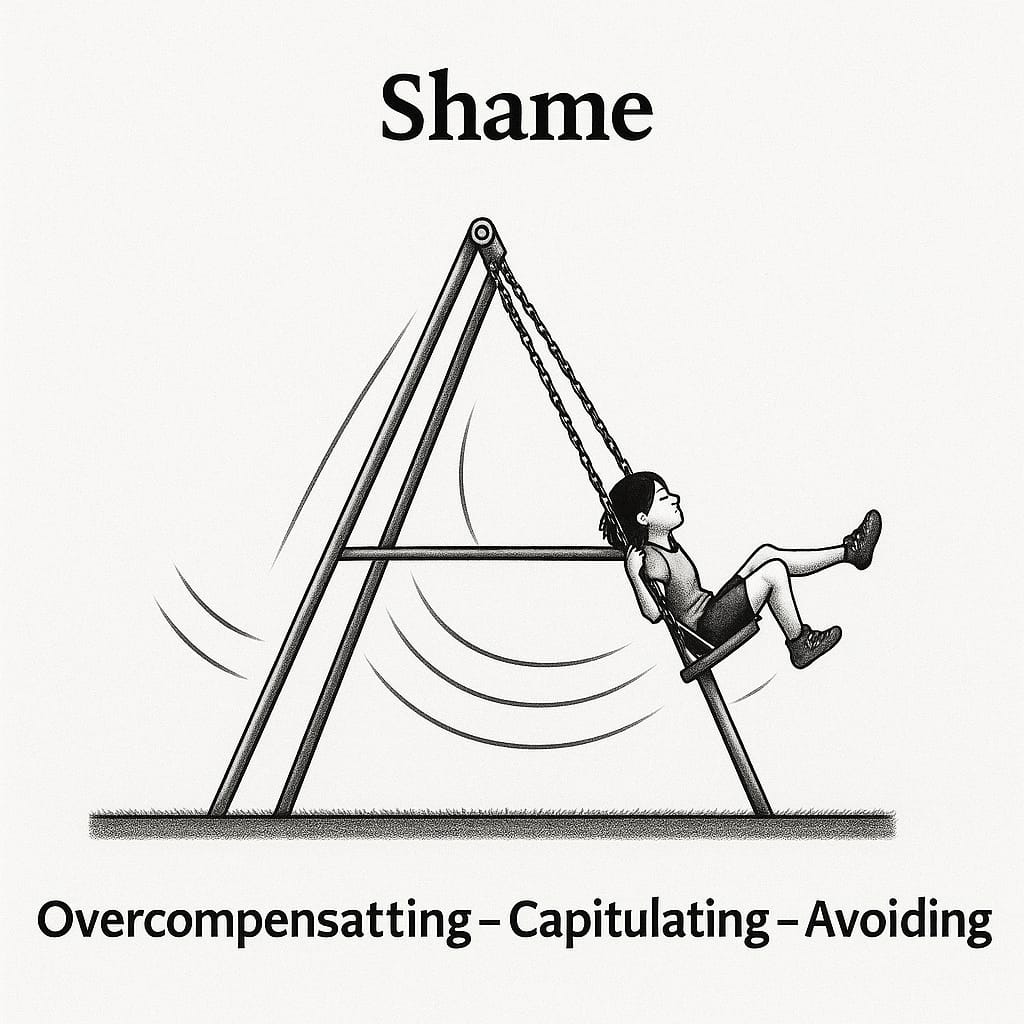

In keeping with the cognitive–behavioural tradition, the NA-CBT process begins with comprehensive history taking that leads to a case conceptualisation uniquely termed the Pendulum-Effect formulation. NA-CBT proposes that, much like the pendulum of a traditional clock, individuals tend to oscillate between maladaptive coping mechanisms, often outside of conscious awareness. This continual oscillation reinforces dominant core affects such as shame, guilt, fear and self-hatred. These affects are sustained by deeply rooted beliefs or negative self-views that function like narrow lenses through which individuals perceive themselves, their future prospects, and significant others. Such lenses accommodate and perpetuate internalised shame, self-loathing, and guilt, for example: “I am unlovable and unattractive, and nobody wants me.”

It is important to pause here and note that neuroaffective research indicates that the affective states we experience do not always have accurate linguistic equivalents. For instance, Japanese culture includes a term for the emotion one feels after receiving a bad haircut. In many Western cultures, we lack equally precise labels for some moment-to-moment affective states. Limiting narratives can further interfere with the affective experience because language is frequently used as an intensity modulator. For example, thinking or saying “I am feeling really sad right now” can amplify what might initially be a mild “lack of energy” on a rainy day. Given that rain is not an unusual phenomenon in the UK, “sadness” may not be the most accurate descriptor, and it may even elevate the feeling through autosuggestion.

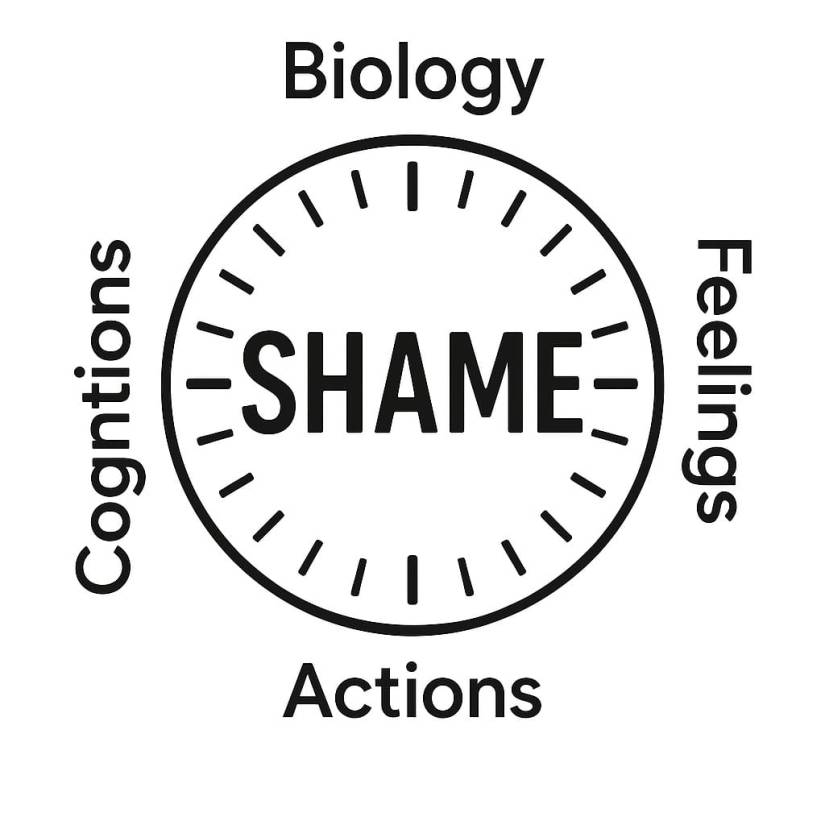

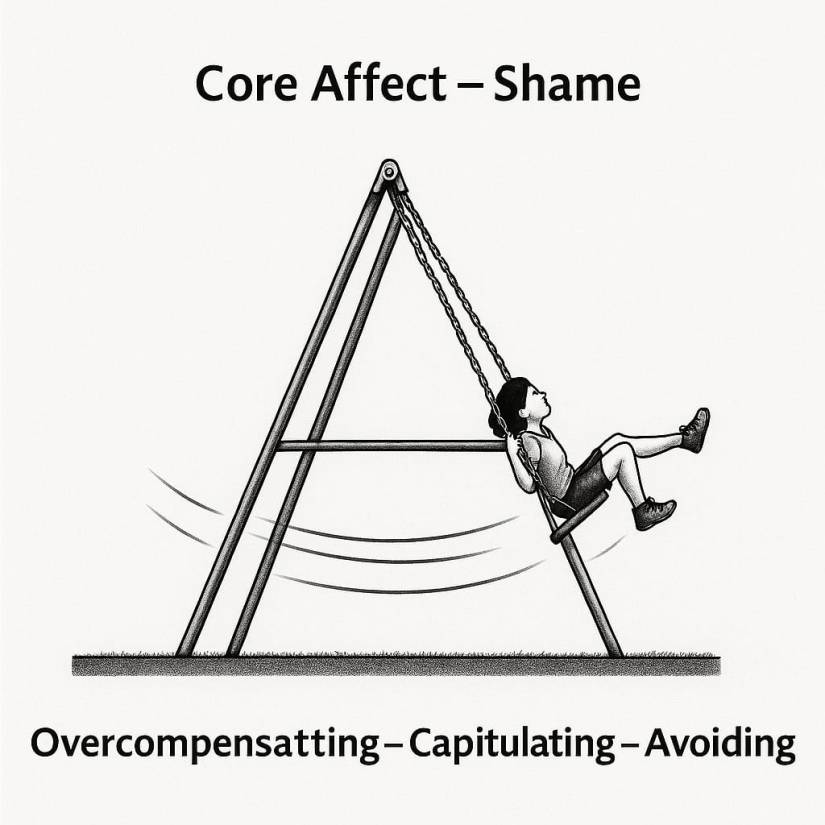

The oscillating Pendulum-Effect suggests that the core affect of shame and/or self-hatred, symbolically located at the centre of the clock’s face, represents the central mechanism driving the system. The core mechanism does not turn the clock without the oscillating movement. In other words, shame, guilt, or self-disgust are constantly perpetuated by reinforcing, self-sabotaging life strategies such as overcompensation, avoidance, and capitulation (or surrendering). These are designed with the precision of an internal clock mechanism and rehearsed over many years.

Equally important is the relationship these coping mechanisms have with each other, the swinging or oscillating effect. People move between these strategies in predictable ways, and this motion becomes central to both assessment and treatment.

Overcompensation

Overcompensation reflects an enduring difficulty in internally saying to oneself: “This is good enough,” “I am good enough,” “I am not helpless or powerless,” or “I am lovable and accepted.” Because one’s worth, value, and personal image depend almost entirely on external validation, internal validation is not perceived as an option. Reassurance seeking, approval, and feeling accepted and appreciated by others become primary goals.

Paying intense attention to one’s appearance, taking provocative selfies for social media, seeking multiple cosmetic or aesthetic procedures, or engaging in elaborate beautification rituals, can feel necessary, even when objective evidence suggests they are excessive. The intention is typically not to attract more sexual attention or partners per se, but to feed a persistent hunger rooted in shame and self-dislike.

A common motto for overcompensators might be: “If someone says jump, I ask how high.” This can become an apparently effective strategy for keeping people close and ensuring that one is seen as a “good friend.” Doing numerous favours, being excessively helpful, showering friends with unexpected gifts or extravagant gestures when they are not required, these behaviours are rarely sustainable and can be costly both emotionally and financially. Over time, this pattern almost inevitably leads to greater self-hatred and resentment toward others, especially when friends do not reciprocate. It becomes a safety mechanism: buying someone’s friendship and trying to keep them close in the long term. However, because these actions lack authenticity, they are more likely to fail.

Another form of overcompensation is the relentless need to control everything or “take control.” This may involve constantly shifting goalposts, doing more and more, or aiming ever higher. A long list of rigid rules, “shoulds,” “musts,” and “if… then…” statements, drives these behaviours, for example: “If I am not always super-nice and performing at 100%, people will reject me.”

Frequent episodes of hyperarousal at work may lead to self-doubt, second-guessing, and repetitive checking: reading and re-reading emails before sending, repeatedly reviewing completed tasks, or staying late to ensure nothing can be criticised. Working hours are extended, leading to exhaustion, guilt, and eventually burnout. Overcompensation rarely provides the long-term relief it promises.

Avoidance

Avoidance is equally diverse. It can manifest as social withdrawal, chronic introversion, avoiding close relationships or intimacy, and even avoiding sex. On the surface, avoidance appears to be the opposite of overcompensation, yet these strategies often complement and reinforce each other – this is the essence of the oscillating effect. For example: “I overcompensate by being extremely provocative and flirtatious online, but in reality I avoid intimacy at all costs, because I fear being ‘found out’ and humiliated.”

Procrastination and lateness can also be understood through this lens: “Looking this good takes time and effort; I cannot afford to look bad on the outside given how rotten I feel on the inside.”

Similarly, “I can work on this later, when I am ready and better prepared” becomes a familiar refrain. When self-worth depends on external validation, it matters deeply how others perceive one’s abilities and competence. Ordinary tasks, such as writing a report or completing a project, acquire overwhelming importance. The sense of being “not ready” or “not just right” fuels avoidance. Procrastination offers short-term relief, but in the long run it reinforces shame and self-criticism.

Capitulating or Surrendering

Capitulating or surrendering is the ultimate self-sabotaging strategy. It involves attacking one’s own confidence and accepting, often unconsciously and unconditionally, the belief that one is “not good enough,” “helpless,” “a failure,” or whatever the dominant shame-based narrative might be.

This can sound like: “Since I am so bad, what does it matter anyway?” or “Since I am so bad, let’s be bad—let me show you how bad I really am.” Surrendering can become a licence to act out of character, for example by drinking excessively, engaging in risky sexual behaviour, or making impulsive decisions. These behaviours rarely alleviate shame; instead, they strengthen the sense of guilt and self-disgust, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Not celebrating one’s successes is another subtle form of surrendering. Achieving a goal becomes a mere “box-ticking exercise” instead of a meaningful achievement. Over time, celebration and self-acknowledgement disappear entirely.

From Not Good Enough to a New Sense of Self

Many people struggle with a deep, core sense of being ashamed, invisible, or “not good enough.” The first step forward is to bring this into awareness in a non-blaming, non-critical way by examining how we cover it up.

Key questions include:

- What am I doing on a daily basis in order not to feel bad, ashamed, or invisible?

- How do I self-sabotage or surrender into the shame of not being good enough?

- What do I avoid far too often?

- How do I overcompensate day to day?

- How would I best describe my self-imposed rules that sometimes help but more often end up serving the very shame they are meant to eliminate?

Understanding our rules, compensations, avoidances, and capitulations, together with their justifications and rigid guidelines, is the breaching point. Reaching this point marks an important milestone: the beginning of a new sense of self, or rather the process of reinventing oneself.

This is also the right time to learn new coping strategies: to “fake it till you make it,” to “act as if” one is good enough, loved, and accepted. It involves becoming more assertive and taking more risks by sometimes acting the opposite of what one’s gut is suggesting.

The journey from a “shamed and scared inner child” to a “confident and independent healthy adult” can be long and challenging, but each successful step is a small win and deserves to be celebrated. There is no single standard path; people respond and learn differently. Artistic journals, audio recordings, written diaries, visual trackers, or even simple “golden stars” can become powerful reminders of the journey taken.

Sarah: case study [1]

To illustrate how internalised shame perpetuates itself through oscillation between overcompensation, surrendering, and avoidance, consider the case of Sarah.

Sarah is a successful paralegal in the City who has struggled with shame-related feelings for most of her life. She is a natural overcompensator, constantly making herself available, useful, and well-liked by everyone, even when completely exhausted and burned out. She hates the idea of letting her colleagues down, and at work her efforts are highly appreciated. Sarah is aware of this dynamic, but she attributes her popularity solely to hard, exhausting work, long hours, and an inability to say ‘No’.

Typically, as Christmas approaches and party invitations begin to accumulate on her desk, she shifts into surrendering, accompanied by harsh self-criticism: ‘I’m not going to perform well; I drink too much to calm my nerves; I’ve put on weight this year; nobody actually likes me for who I am’, and so on. This is followed by avoidance, such as not reading the invitations, not following up, and not responding. All these actions occur before any event takes place and are intended to avoid social situations she feels destined to fail. They are fuelled and justified by exaggerated predictions of social embarrassment and other imagined ‘disasters’.

Her surrendering responses also involve fortune-telling, vivid images of social awkwardness, and rejection of support such as, declining a colleague’s offer to accompany her to one of the events. This particular colleague, who was both insistent and single, turned out to be genuinely interested in dating her, something that only became clear later in therapy. Her surrendering stance prevented her from recognising his intentions at the time. These surrendering strategies then justify the subsequent avoidant behaviour and withdrawal, which inevitably lead to isolation, loneliness, guilt, self-disgust, and intensified self-criticism, ultimately reinforcing her shame-based beliefs.

A simple chain analysis suggests that Sarah overcompensates until she burns out, then falls into self-criticism through surrendering, which is then followed by withdrawal and other avoidant behaviours. This completes a self-perpetuating emotional trap, representing the mechanism that enables the back-and-forth ‘swing of the pendulum‘ through these emotions and associated behaviours over time. These patterns can be best understood as emotion-driven behaviours.

The pendulum as both a timekeeper and a regulator

The metaphor of the pendulum is intended not only to depict the timing and rhythm of these emotional swings but also to serve as a regulatory tool. In therapy, it helps to disrupt the behaviours that maintain the swinging mechanism—or emotional trap. Several reinforcing mechanisms may be active, each of which can be clearly mapped using the Pendulum-Effect formulation. Once these mechanisms are fully understood, they are collaboratively examined, modified, and finely tuned with the patient in a strategic yet compassionate manner throughout therapy.

This work unfolds across six modules in total, the middle four of which are flexible and interchangeable treatment modules:

- Assessment – Pendulum Formulation

- Psychoeducation and Motivation

- Physical Strengthening

- The Integrated-Self

- Coping Skills Training

- Skills Consolidation & Problems Prevention

Module 1: Assessment and the Pendulum-Effect Formulation

The initial consultation serves as the assessment stage, providing an opportunity to establish a strong therapeutic bond through empathic mentalisation. During this phase, the therapist introduces the Pendulum-Effect formulation, helping the client understand their core emotional patterns and the coping strategies, overcompensation, surrendering, and avoidance, that shape their difficulties. This foundation guides the collaborative work that follows across the remaining modules.

Module 2: Psychoeducation & Motivational Enhancement

This module focuses on strengthening resilience, motivation, self-efficacy, and problem-solving skills. Through clear and accessible psychoeducation, clients gain a deeper understanding of their emotional and behavioural patterns, as well as the mechanisms that sustain them. The Pendulum-Effect formulation is actively used to the client’s advantage at this stage to cultivate self-appreciation, helping them recognise their existing resources and coping strategies, and further build motivation for meaningful and lasting change.

Module 3: Physical Strengthening — TED’s your best friend!

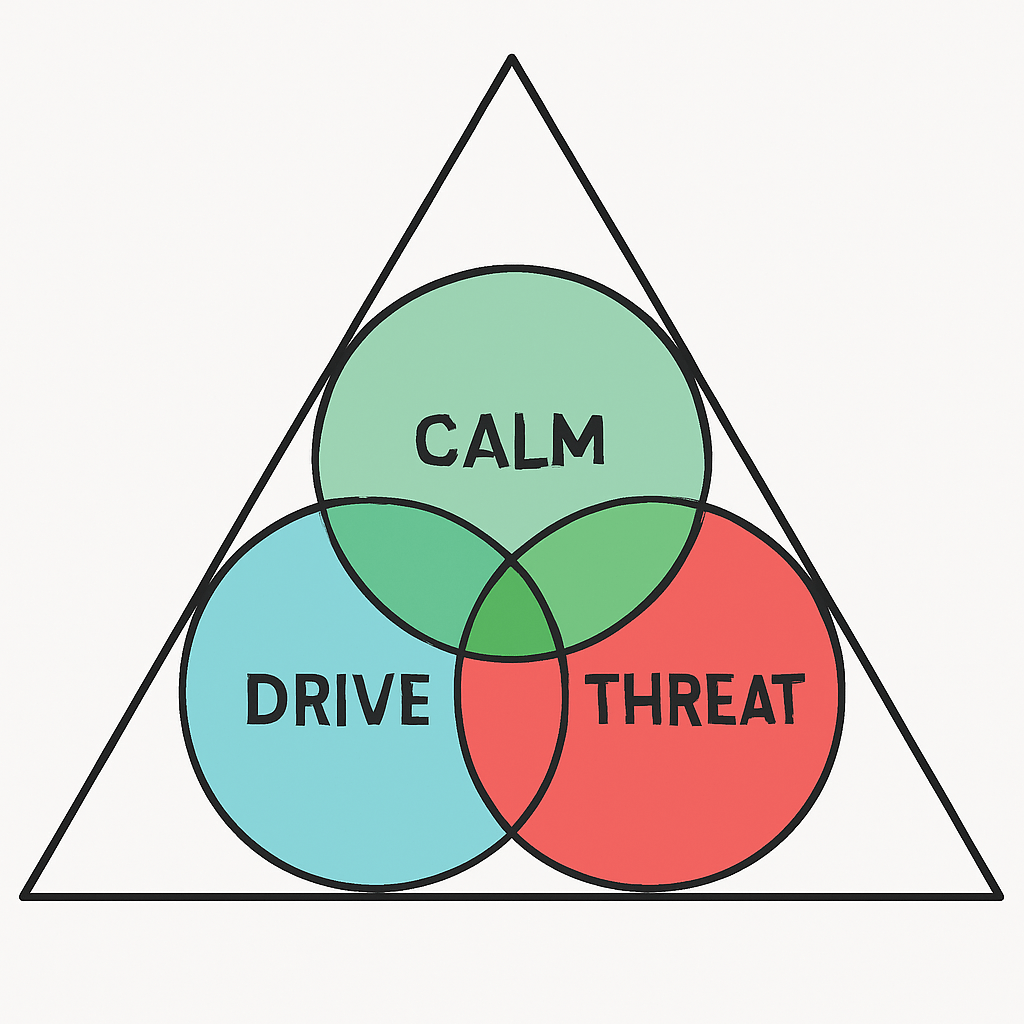

Within the NeuroAffective-CBT® framework, TED (Tired, Exercise, Diet) functions as a biologically grounded scaffold of self-regulation that stabilises the Body–Brain–Affect triangle. It is not a list of prohibitions, restrictions, or lifestyle commandments, but rather a set of neuro-behavioural levers capable of influencing key biological systems, including dopamine and serotonin pathways, adrenaline responses, immune signalling, circadian rhythms, and the vagus-mediated gut–brain axis, the intricate ‘wiring loom’ connecting body and mind.

‘TED your way out of trouble‘ has become a favourite phrase within NA-CBT, and for good reason: strengthening the body’s regulatory systems lays the foundation for emotional and cognitive flexibility.

To explore this often overlooked, but essential, dimension of therapy in greater depth, please follow the TED-dedicated article series, where each component is examined in detail and contextualised within modern neuroaffective science.

Module 4: The Development of an Integrated-Self

Internalised shame, often accompanied by self-dislike and self-loathing, creates a profound disconnect between who a person believes they are and who they wish to be. The aim of this module is to help integrate these two extremes, allowing the individual to develop a more coherent, compassionate, and resilient sense of self.

This work involves trauma processing, cognitive reframing and integration, shifting from self-hatred and relentless self-criticism toward self-acceptance and self-compassion. A central part of this process is a non-judgemental understanding of one’s coping mechanisms through the Pendulum-Effect formulation. These patterns, whether overcompensation, surrendering, or avoidance, are recognised as survival strategies that once served a purpose, even if they are now limiting or counterproductive.

When processing a traumatic episode, the therapist’s instructions follow a deliberate and structured sequence. First, the client is guided to notice the location of the affect and the physiological reaction it triggers. Next, they are encouraged to label the negative affect (‘name it to tame it’), whether it is shame, guilt, anger, or fear, and to identify the accompanying bodily sensations such as tightness in the chest, a constriction around the head, a dry knot in the throat, or pain in the abdomen or around the heart. The client then rates the intensity of these sensations on a 0–10 scale in order to track shifts in their physiological state and indeed learns to mindfully observe their physiological and emotional fluctuations and the eventual reduction within the space of a few minutes of recollection. This structured sequence helps reduce amygdala-driven reactivity by training the attention and focusing on abdominal breathing patterns and progressive muscle relaxation. Also, reframing the traumatic experience from an overwhelming emotional event into a umbrella conclusion about the self, world and future prospects (‘I am wiser and stronger because of it’; ‘I am a survival, not a victim’). The traumatic experience is safely contained and relieved in the present, even reduced to a series of manageable cognitive, muscular and physiological responses. This type of processing trains the trauma survivor to adopt the stance of an observer rather than a passive recipient of the trauma narrative. The emotional episodes gradually come to be perceived as natural fluctuations rather than threats, fostering greater acceptance and contributing to a healthier, more adaptive self-concept.

Module 5: Behavioural Coping Skills

This module provides targeted training in exposure (real-life and/or imaginal) to situations that feel overwhelming or unmanageable, alongside skills in assertiveness, grounding, and method acting. Method-acting techniques help individuals embody a desired attitude, behavioural stance, or set of character traits, sometimes even experimenting with a more adaptive or empowered ‘new persona’. This experiential approach accelerates the integration of new emotional, cognitive, and behavioural responses into everyday life.

Module 5 also supports the client in exploring authentic living by identifying new personal goals and values and, embracing the idea of ‘a new beginning’ – ‘What would life be like if I truly believed I am loved and accepted?’ Through this process, clients learn to replace maladaptive, emotion-driven, and self-sabotaging behaviours, whether overcompensatory, avoidant, or surrendering, with more intentional and value-aligned actions.

Module 6: Skills Consolidation & Relapse Prevention

The final module focuses on consolidating newly acquired skills and developing a realistic plan for maintaining progress. Together with the therapist, the client identifies future goals, anticipates potential obstacles, and prepares strategies for managing setbacks with confidence. This stage strengthens long-term resilience and ensures that the gains achieved throughout therapy are carried forward into everyday life.

A revolving-door policy operates post-treatment, often for months or even years. This provides valuable opportunities for booster sessions, ongoing support, and follow-up work, allowing both client and clinician to revisit progress, adjust strategies, and reinforce long-term stability.

The underpinning fundamentals of the approach

Several essential mechanisms underpin NA-CBT. Each treatment module employs a distinct set of skills, but none more essential that the than the ability to build a strong therapeutic alliance. I coined the term empathic mentalisation to describe therapist’s skilful ability to connect with his client in a way that would allow the therapist to not just hear and understand patients’ vulnerabilities, at a prefrontal or intellectual level, but instead to allow himself, to feel client’s pain in a way which will help the client feel felt.

While some attachment-based therapies may claim similar relational engagement, this is where the resemblance ends. In NA-CBT, the therapeutic relationship is not used as a transference or countertransference medium. The therapist remains consistently aware of the client’s goals and maintains a high degree of structure and direction over the therapeutic agenda. The relationship is guided intentionally and collaboratively throughout treatment. Transference and countertransference processes are treated as opportunities for open dialogue, learning, and behavioural insight, not as primary drivers of therapeutic progress. At the core of NA-CBT are the principles of challenging, restructuring, and reframing irrational self-beliefs, installing new coping and emotional-regulation skills, and disrupting unhelpful behavioural patterns.

Psychoeducation is another foundational element of the model. Decades of CBT research show that high-quality psychological education strengthens trust in both the therapist and the therapeutic process. Studies consistently demonstrate that therapist expertise, confidence, clarity of explanation, knowledge of psychopathology, and treatment integrity all contribute significantly to improved outcomes (Donker et al., 2009; Podell et al., 2013). NA-CBT builds on this evidence, using psychoeducation to establish a clear framework of understanding that empowers clients from the very beginning of treatment.

NeuroAffective-CBT provides an excellent platform for integrating emerging disciplines such as neuroscience, nutritional psychiatry, physiology, and cognitive psychology, fields that have expanded significantly over the past 30 to 40 years yet remain underutilised in many psychotherapy models.

Cognitive psychology and meta-awareness research (e.g., Wells A., 2009; Wells A., 2019; Padesky C., 1997), the Interacting Cognitive Subsystems (ICS) Model (Barnard & Teasdale, 1989, 2008), and the Adaptive Information Processing (AIP) model (Shapiro, 1989, 2001, 2007, 2009) all propose that memories are processed in a highly organised and structured manner. Incoming information is filtered through templates shaped by past experiences and internal models of self and world. When childhood experiences are traumatic, memories are often stored in rigid, unprocessed formats that fail to integrate into the broader autobiographical narrative. These unprocessed memories contribute to persistent emotional vulnerabilities and disturbances in self-concept. As a result, unresolved, unintegrated, or shame-laden memories, whether profoundly traumatic or simply distressing, often lie at the core of chronic shame, self-disgust, and low self-esteem (Schore, 1998; Gilbert, 2006; Siegel, 2007; Gilbert, 2011).

A clinical example illustrates the importance of memory specificity (also referred to as hot memories). Jane’s mother would often smile warmly moments before unleashing verbal or physical abuse. As an adult, Jane grew suspicious of ‘nice‘ people who smiled at her and instead gravitated toward individuals she perceived as more ‘genuine‘, often those who were angry, moody, or unpredictable. Unsurprisingly, her relationship patterns became consistently unhealthy and self-sabotaging. Neuroaffective science explains that repeated childhood experiences lay down neural pathways that generate urges, habits, and automatic interpretations, such as: ‘My colleague is too smiley, something must be wrong.. I should keep my distance.’

In NA-CBT, therapy focuses on targeting these specific or hot memories, which activate cascades of negative affect and self-defeating behaviours. This can be more effective than attempting to process the broader abuse narrative; for example, Jane’s overall relationship with her mother and her mother’s chronic unpredictability. Such global narratives tend to become cognitively assimilated over many years in distorted ways (e.g., ‘I was a naughty child who deserved it‘). In contrast, specific memories offer clearer, more precise access points for emotional processing and integration.

During module 4 – Developing an Integrated-Self, the client may be asked to recall the most distressing aspect of an earlier traumatic or shame-laden memory, along with the associated shame-based beliefs and bodily sensations. Increasing attentional focus on internal physiological shifts, particularly psychosomatic reactions linked to shame, is central at this stage. Clients are encouraged to ‘pay attention to what is happening inside you right now, especially the location and intensity of the distress’. Simultaneously, the client is guided to narrate the triggering (specific) memory in detail, with minimal deviation or avoidance. It is expected that certain elements of the memory may have been previously suppressed, fragmented, or pushed aside.

The therapist’s instructions follow a clear and structured sequence:

- Notice the location of the affect and the associated physiological reaction.

- Name it to tame it – label the affect (shame, guilt, anger or fear) and identify the corresponding bodily sensations (e.g., tightness in the chest, a pressure around the head, a painful knot in the throat, or discomfort in the abdomen or chest).

- Rate the intensity of these sensations (0–10) to monitor shifts in physiological arousal.

- Breathe into the area of tension and progressively relax the body.

- Observe the affective fluctuations and their gradual subsidence.

- Reframing the experience (including updated autobiographical belief)

This sequence reduces amygdala-driven reactivity by reframing the trauma response as a combination of maladaptive self-beliefs and manageable muscular and physiological sensations. Through repeated practice, clients learn to adopt the stance of an observer, rather than a passive recipient, of their trauma narrative. Over time, emotional and bodily fluctuations come to be experienced as natural, gradual variations rather than overwhelming threats, an essential step toward increasing acceptance and integrating a healthier, more adaptive sense of self.

If appropriately trained, the therapist may also employ a specific form of memory processing known as bilateral stimulation. Although the research in this area has at times been debated, more recent evidence has been favourable, particularly regarding hands-tapping protocols. Several neuropsychological, developmental, and attachment studies (Kirsch et al., 2007) highlight the therapeutic value of appropriate, clinically attuned physical touch, noting its association with the release of endorphins, serotonin, and dopamine, as well as the formation of new neural pathways. These mechanisms ultimately contribute to improved self-regulation (Siegel, 2007).

Traumatic memory processing is one area in which NA-CBT overlaps with Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR). EMDR is a structured therapeutic approach that uses bilateral stimulation, most commonly eye movements or auditory tones, to facilitate the processing and integration of traumatic memories. However, unlike EMDR, NeuroAffective-CBT is firmly grounded in the evidence-based cognitive and behavioural practices that have demonstrated effectiveness over the past 50–60 years. NA-CBT remains fundamentally a behavioural approach, centred on active, progressive change through the adoption of new and more adaptive behavioural strategies (see Case Study 2).

Case study [2]:

John experienced intrusive flashbacks of physical and emotional abuse whenever his manager raised her voice in the office. After only three hours of desensitisation using bilateral sensory processing (e.g., tapping), the frequency and intensity of his flashbacks reduced dramatically, eventually disappearing altogether. John also reported a marked reduction in hyperarousal.

To prevent relapse and strengthen the newly formed competing memory between sessions, John and his therapist agreed on several behavioural changes for him to implement at work. These included adopting a different attitude and mindset, increasing awareness of his body language and internal reactions, taking notes to track these shifts, and improving his posture. He also prepared a set of responses for potentially challenging situations that would require assertiveness. These strategies and coping skills were rehearsed repeatedly, through imagery rehearsal, role plays, and other behavioural exercises, both inside and outside the therapy room.

Selecting the Appropriate Trauma-Focused Technique

Despite the positive outcomes and clinical success reported with bilateral sensory processing, NA-CBT recognises that narrative exposure, reliving, imaginal and in-vivo exposure, or the processing of activating (hot) memories may be more appropriate interventions for certain trauma presentations. For instance, when a male therapist is working with a female survivor of rape, bilateral stimulation may not feel safe due to the interpersonal dynamics involved. In such cases, memory integration is best achieved through detailed narrative work and behavioural evidence-gathering rather than sensory input.

Therapeutic effectiveness depends heavily on the trust between therapist and client, as well as the client’s expectations of both the therapist and the chosen technique (Kumpasoğlu et al., 2024; Meichenbaum, 2017). The therapist’s expertise and confidence also influence treatment outcomes, since the appropriate selection of technique requires strong clinical judgement and the ability to tailor interventions to the client’s needs, personality, values, and current circumstances (Bartle-Haring et al., 2022; Castonguay & Beutler, 2006).

The Role of Emotional Desensitisation

Regardless of the method, it is essential during emotional or traumatic desensitisation that individuals struggling with shame, fear, anger, or guilt re-experience the relevant memories without becoming overwhelmed, within a safe therapeutic environment that helps them bridge past and present. Clinical experience suggests that bilateral processing can sometimes achieve this more reliably than narrative or imaginal reliving.

Bilateral stimulation works through the multitasking demand of simultaneous focused and distributed attention, enabling the brain to access traumatic, frightening, or maladaptive experiences while activating processing mechanisms that promote transformation and integration. Once fully integrated, the event—and the adaptive meaning derived from it—remains accessible, but the previously associated hyperarousal or shutdown responses diminish significantly or disappear altogether.

For individuals affected by shame, re-experiencing memories without becoming emotionally flooded is crucial. Clinical and neuroaffective observations indicate that bilateral processing can sometimes achieve this more consistently than traditional exposure methods. The multitasking nature of bilateral stimulation appears to activate neural pathways that facilitate the processing and integration of emotional material. When integration is successful, the client can articulate the memory and the learning derived from it, but the corresponding hyper- or hypo-arousal responses no longer accompany the recollection.

Self-Efficacy, Mastery, and the Modulation of Dissociation

An additional and clinically meaningful phenomenon often emerges during bilateral sensory processing (e.g., tapping, alternating visual cues, or other dual-attention techniques). Clients are supported in navigating the internal associations that typically arise during processing. This experience enhances self-efficacy and mastery, particularly the individual’s ability to shift flexibly between re-experiencing the event and returning to present-moment awareness (Oren & Solomon, 2012). This skill reduces dissociative tendencies and improves attention-orientation capacities (Goldin, 2009).

Several trauma studies suggest that physical touch, when used appropriately and therapeutically, can counteract dissociation and foster grounding, safety, and embodied presence. Although the use of touch remains culturally sensitive, particularly between genders, clinical experience, neuroaffective findings, and even anthropological research all indicate that attuned touch can support emotional regulation and integration.

With regard to self-efficacy, Oren and Solomon (2012) propose that experiences of mastery become encoded as adaptive information within memory networks. This perspective aligns with the work of Teasdale and Barnard (1993), Donald Meichenbaum (2017), and Albert Bandura’s (1989) theory of self-efficacy. Together, these frameworks suggest that once a traumatic event is processed and integrated, it can be recalled without the previously attached emotional intensity, allowing the client to remember without reliving.

Attention Training and Mindfulness Mechanisms

Another key mechanism in NA-CBT involves attention training, particularly through mindfulness-based instructions. During desensitisation or memory processing, clients are encouraged to ‘let whatever happens, happen’ and to ‘notice whatever thoughts arise‘, consistent with mindfulness principles (Goldin et al., 2009; Siegel, 2007; De Jongh et al., 2013; Wells A., 2019).

Imagery-based desensitisation and exposure exercises, commonly used in mindfulness and clinical hypnosis, further support the creation of psychological distance. According to working memory theory, maintaining dual tasks results in cognitive overload, which reduces the vividness and emotional impact of distressing material. Although the working memory literature shows some variability, findings from mindfulness, ICS, EMDR, and clinical hypnosis research offer convergent evidence for this mechanism. Maxfield et al. (2008) propose that dual-attention tasks help forge new associative links between related material and the original memory, transforming how the memory is stored within the network.

Final Thoughts

I genuinely stand on the shoulders of giants. Many clinicians have shaped my work over the years, but none more profoundly than my mentor, colleague, and friend Dr Donald Meichenbaum, one of the earliest pioneers of transdiagnostic approaches such as narrative constructivism and stress inoculation training. Psychotherapy continues to evolve, and as Dr Meichenbaum noted in a 2018 Psychotherapy Expert Talks interview, the expanding field of neuroscience, including work on gene expression, is not only cutting edge but highly relevant. Adverse experiences can ‘tune’ stress and emotion systems by altering patterns of gene expression; resilience-building experiences can ‘retune’ these systems in a healthier direction. Psychotherapy and coping skills are therefore, not just simplistic psychological interventions but associated with real biological change over time.

Such developments enrich psychological therapies and help underpin the scientific foundations of models like NeuroAffective-CBT.

It is increasingly clear that the future of psychotherapy will involve a deeper integration of mind and body. Traumatic stress is just one example where working holistically with a client’s psychological and physiological symptoms can lead to more robust and lasting outcomes. This shift will require psychotherapists and psychologists to broaden their expertise beyond traditional cognitive and emotional frameworks to include physiology, nutritional psychiatry, and psychosomatic approaches. The fields of neuroscience, clinical hypnosis, psychosomatic medicine, and biological treatments are only beginning to converge in meaningful ways.

NA-CBT represents one example of what can be achieved under the broader umbrella of Neuroscience and CBT; these new and old integrative, empirically grounded traditions are uniquely positioned to guide holistic approaches to mental health. In this model, the body, brain, and affect are understood as inseparable components of human experience, each informing and supporting the others throughout the therapeutic process.

References:

Bandura, A. (1989). Regulation of cognitive processes through perceived self-efficacy. Developmental Psychology, Vol 25(5), 729-735.

Bartle-Haring, S., Bryant, A. & Whiting, R., 2022.

Therapists’ confidence in their theory of change and outcomes.

Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 48(2), pp.1–16. doi:10.1111/jmft.12593.

Bisson J, Roberts NP, Andrew M, Cooper R, Lewis C (2013). “Psychological therapies for chronic PTSD in adults”. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: CD003388. PMID: 24338345

Brown, S. & Shapiro, F. (2006). EMDR in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Clinical Case Studies, 5, 403–420.

Castonguay, L.G. & Beutler, L.E., 2006. The Principles of Therapeutic Change That Work. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

David, D., Cristea, I. and Hofmann, S.G., 2018. Why cognitive behavioral therapy is the current gold standard of psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, p.4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00004

Davidson, P. & Parker, K. (2001). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 305–316.

De Jongh, A., Ernst, R., Marques, L. & Hornsveld, H. (2013). The impact of eye movements and tones on disturbing memories of patients with PTSD and other mental disorders. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 44, 447–483.

Donker, D., Griffiths, K.G., Cuijpers, P., Christensen, H., (2009). Psychoeducation for depression, anxiety and psychological distress: a meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2009; 7: 79. Published online 2009 Dec 16. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-7-79

Gilbert P., Procter S., (2006). Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism.: overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 13, 353-379.

Gilbert P., 2011. Shame in psychotherapy and the role of compassion focused therapy. In R. L. Dearing & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Shame in the therapy hour (pp. 325-354). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

Goldin P, Ramel W, Gross, J (2009). Mindfulness Meditation Training and Self-Referential Processing in Social Anxiety Disorder: Behavioral and Neural Effects. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23(3): 242-257

Herbert, J., Lilienfeld, S., Lohr, J. et al. (2000). Science and pseudoscience in the development of EMDR. Clinical Psychology Review, 20, 945–971.

Hofmann, A. (2012). EMDR and chronic depression. Paper presented at the EMDR Association UK & Ireland National Workshop and AGM, London.

Jaberghaderi, N., Greenwald, R., Rubin, A. et al (2004). A comparison of CBT and EMDR for sexually abused Iranian girls. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 11, 358–368.

Kumpasoğlu, G.B., Campbell, C., Saunders, R. & Fonagy, P., 2024.

Therapist and treatment credibility in treatment outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clients’ perceptions in individual face-to-face psychotherapies.

Psychotherapy Research.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2023.2298000

Lee, C.W. & Cuijpers, P. (2013). A meta-analysis of the contribution of eye movements in processing emotional memories. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 44, 231–239.

Logie, R. & De Jongh, A. (2014). The ‘Flashforward procedure’: Confronting the catastrophe. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 8, 25–32.

Maxfield, L., Melnyk, W. & Gordon Hayman, C. (2008). A working memory explanation for the effects of eye movements in EMDR. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 2, 247–261.

Meichenbaum, D (2017): “Constructive narrative perspective”. In The Evolution of CBT: a personal and professional journey with Don Meichenbaum. Taylor & Francis Group.

Meichenbaum, D., 2017. The Evolution of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy: A Personal and Professional Journey. Abingdon: Routledge.

Mirea, D., 2018. CBT, what’s all the fuss about? NeuroAffective-CBT® [online]. 25 July. Available at: https://neuroaffectivecbt.com/2018/07/25/cbt-whats-all-the-fuss-about/

Oren, E. & Solomon, R. (2012). EMDR therapy. Revue européenne de psychologie appliquée, 62, 197–203.

Padesky, C. (1997). Schema change process in cognitive therapy. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. Vol 1. (5), 267-278.

Podell J.L., Philip C. Kendall, Elizabeth A. Gosch, Scott N. Compton, John S. March, Anne-Marie Albano, Moira A. Rynn, John T. Walkup, Joel T. Sherrill, Golda S. Ginsburg, Courtney P. Keeton, Boris Birmaher, and John C. Piacentini. Therapist Factors and Outcomes in CBT for Anxiety in Youth. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2013 Apr; 44(2): 89–98. Published online 2013 Mar 18. doi: 10.1037/a0031700

Propper, R. & Christman, S. (2008). Interhemispheric interaction and saccadic horizontal eye movements. Implications for episodic memory, EMDR, and PTSD. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 4, 269–281.

Ray, A. & Zbik, A. (2001).

Rothbaum, B.O., Astin, M.C. & Marsteller, F. (2005). Prolonged exposure versus EMDR for PTSD rape victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(6), 607–616.

Shapiro, F. (1989). Eye movement desensitization. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 20, 211–217.

Shapiro, F. (2001). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Basic principles, protocols and procedures (2nd edn). New York: Guilford Press.

Shapiro, F. (2007). EMDR, adaptive information processing, and case conceptualization. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 1, 68–87.

Shapiro, F. & Maxfield, L. (2002). In the blink of an eye. The Psychologist, 15, 120–124.

Shapiro, R. (2009). EMDR Solutions II. New York: Norton.

Schore, A. (1998). Early shame experiences and infant brain development. In P. Gilbert & B. Andrews (Eds.), Series in affective science. Shame: Interpersonal behavior, psychopathology, and culture (pp. 57-77). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press.

Siegel, D.J. (2007). The mindful brain. New York: Norton.

Soberman, G., Greenwald, R. & Rule, D. (2002). A controlled study of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for boys with conduct problems. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma, 6, 217–236.

Stickgold, R. (2002). EMDR: A putative neurobiological mechanism of action. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58, 61–75.

van den Berg, D. & van der Gaag, M. (2011). Treating trauma in psychosis with EMDR: A pilot study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 43, 664–671.

van den Hout, M., Engelhard, I., Rijkeboer, M. et al. (2011). EMDR: Eye movements superior to beeps in taxing working memory and reducing vividness of recollections. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 92–98.

Watts BV, Schnurr PP, Mayo L, Young-Xu Y, Weeks WB, Friedman MJ (2013). Meta-analysis of the efficacy of treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74 (6): e541–55

Wells, A., 2009. Metacognitive Therapy for Anxiety and Depression. New York: Guilford Press.

Wells, A., 2019. Breaking the cybernetic code: Understanding and treating the human metacognitive control system. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2621.

Additional reading to consider:

For more information about Dr Donald Meichenbaum‘s career and research click here !