Understanding the current clinical context

In a 2018 article “CBT, what’s all the fuss about“, Daniel Mirea highlights the ongoing confusion surrounding the mental health treatment landscape. Despite the years that have passed since, the core issues persist, individuals struggling with mental health continue to feel uncertain about what they need, what treatment options are available, and what their prognosis might look like. This ambiguity makes it difficult for many to navigate the complex world of psychotherapy and psychological support, leaving them unsure about the most appropriate course of action for their well-being.

The Emergence of NA-CBT ® in parallel with Integrative-CBT

Against this backdrop, Integrative Cognitive-Behavioural Therapies (I-CBT) have emerged as a potential “fourth wave” in the evolution of CBT which would eventually be overshadowed by the 2019 pandemic. Nonetheless, I-CBT points to a family of contemporary therapeutic approaches that retain the evidence-based strengths of traditional CBT while expanding its scope to address the multifaceted nature of modern psychological suffering.

The term “Integrative-CBT” was first introduced in 2017 at the 9th International Congress of Cognitive Therapy, held at Babeș-Bolyai University in Transylvania. The conference, attended by renowned clinicians and psychologists, placed particular focus on the emerging influence of digital technology on psychotherapy. In hindsight, this focus was prescient: within two years, a global pandemic would push psychotherapy almost exclusively online, redefining practices such as in vivo exposure and accelerating the need for flexible, digitally adaptable therapeutic approaches. Unfortunately, subsequent global challenges, including the pandemic and ongoing geopolitical unrest, have diverted attention from the development and dissemination of I-CBT, despite its relevance. These therapies emphasize flexibility, technological integration, and responsiveness to new psychosocial stressors. Rather than being strictly diagnosis-driven, I-CBT, like NeuroAffective-CBT® (aka NA-CBT®), incorporates techniques from various traditions, neuroscience, and biopsychosocial models to respond to the full spectrum of human emotional experience.

A defining feature of I-CBT, and particularly NA-CBT, is the recognition of the profound psychological impact of the digital age and artificial intelligence. On one hand, technology enables new learning styles – essential for neuroplasticity (Uddin, L. Q. , 2021), faster research, enhanced communication, and remote therapeutic. On the other, it introduces new stressors, chronic multitasking, information overload, constant social comparison, and reduced in-person social interaction, that can impair emotion regulation, attention, and self-worth.

The digital environment has reshaped how individuals process information, connect socially, and experience emotion. For example, social media exposure has been linked to chronic self-criticism and low self-esteem, while digital overstimulation is associated with anxiety and attention dysregulation. Moreover, reduced in-person interaction weakens opportunities for affective mirroring and co-regulation, both essential to empathy development and emotional resilience. These challenges are particularly pronounced among younger populations and demand a therapeutic response that is both emotionally attuned and digitally aware. NA-CBT incorporates these realities into its treatment strategies, recognising that a rigid medical disease model (assess + diagnose + treat) has many shortcomings but also, building emotional resilience in a digitally saturated world requires new skills and frameworks. Studies by Twenge & Campbell (2018) and Elhai, Levine, & Hall (2017) have demonstrated clear links between smartphone use, social media exposure, depressive symptoms, and impaired affect regulation. Complex emotions such as shame, guilt, self-hatred can be both generated and perpetuated by online interactions.

Further empirical evidence supports the link between digital overuse and impaired self-regulation, a key target of NA‑CBT’s digital-awareness interventions. For example, excessive smartphone use has been shown to impair executive functioning, increase mind-wandering, and elevate the frequency of cognitive failures, factors closely tied to negative mood symptoms and attention problems in students (Zheng et al., 2023). Additionally, mobile phone addiction has been associated with significant emotion regulation difficulties, including diminished effectiveness in strategies like cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression (Zhou et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023; Elhai et al., 2017). These findings highlight the need for therapy models like NA‑CBT to incorporate digital literacy and self-regulation as foundational treatment components.

The Contribution of NA-CBT

It is now more clear than ever, that the world is evolving at a fast pace due to human ingenuity and creativity. Innovation in the digital, engineering and artificial intelligence aim to make our life interesting and convenient but with significant hidden costs.

NeuroAffective-CBT, developed by Daniel Mirea, predates the formal emergence of the I-CBT movement but exemplifies its core principles. NA-CBT offers a sophisticated, integrative model that blends traditional CBT methods with insights from neuroscience, affect theory, biology and somatic psychology. What distinguishes NA-CBT is its particular focus on emotional states that are difficult to articulate or categorize, especially shame-based experiences such as chronic shame and guilt, self-loathing, and feelings of worthlessness. These states often lie outside the reach of traditional, diagnosis-oriented CBT protocols. NA-CBT addresses this gap by integrating cognitive and behavioural methods with an understanding of brain-based emotional processes, body-mind feedback loops, and flexible, modular treatment planning adapted to a new digital age.

The model is designed to meet clients where they are emotionally, neurologically, and behaviourally. Rather than forcing individuals into rigid diagnostic boxes, NA-CBT builds a therapeutic framework around lived emotional realities, drawing on somatic techniques, empathic mentalisation, and trauma-informed practices. The result is a highly adaptable and emotionally resonant approach that supports deep and lasting change.

As the pace of innovation accelerates and continues to reshape human psychology, therapeutic models must evolve accordingly. NA-CBT represents a forward-looking response to this need, one that honors the scientific roots of CBT while embracing the complexity of contemporary emotional life. By addressing the unique challenges of a hyperconnected, overstimulated world, NA-CBT offers clinicians a powerful tool for guiding clients toward emotional integration and psychological well-being.

The Intersection of Thought, Emotion, Behaviour and Biology

Cognitive-Behavioural methods: traditional CBT focuses on the connection between thoughts, feelings, and behaviours, with an emphasis on identifying and changing cognitive distortions and maladaptive behaviours. CBT helps individuals become more aware of their thought patterns and how they affect emotional and behavioural responses. NA-CBT continues to utilise these core principles but seeks to go beyond the limitations of traditional CBT by incorporating additional approaches and insights from the fields of neurobiology and physiology in particular.

The Neurobiology and Neuroaffective Understanding

NA-CBT draws upon contemporary neuroscience, attachment theory, and even mammalian behavioural studies to better understand how complex or “undiagnosable” emotions are processed in the brain and body. Emotions such as shame, guilt, and self-loathing often lie beneath the surface of diagnosable disorders but exert a powerful influence on behaviour, physiology, and well-being. These emotional states are not merely psychological phenomena, they are deeply embodied experiences that activate specific brain structures (e.g., the amygdala), engage neurochemical responses, and produce measurable physiological changes.

The Brain’s Core Function: Predict and Protect

At the heart of the brain’s function is a singular goal: survival. The brain works continuously and in close partnership with the mind to anticipate threats and initiate behaviours that keep the organism safe. It does this through prediction, detecting patterns, forecasting danger, and triggering the release of emotional signals to prepare the body for action. In this sense, emotions are not abstract feelings, they are the brain’s calls for specific, adaptive behaviours. For example, fear prompts avoidance or escape; anger prepares the body for confrontation; sadness signals loss and seeks social support.

Understanding Shame and Guilt as Adaptive

While fear and anger are commonly addressed in psychotherapy, NA-CBT pays particular attention to less obvious and often overlooked emotions such as shame and guilt. These emotions are not dysfunctional by default, in fact, they serve critical self-regulatory functions.

Take shame, for example. It acts as a powerful internal alarm, designed to:

-

Reduce arousal in overwhelming social situations

-

Inhibit actions that might lead to exclusion or danger

-

Motivate behavioural correction in the service of group belonging

The experience of shame, “I can’t bear this feeling; I must do something to stop it”, often results in immediate, sometimes maladaptive, actions aimed at relief or concealment. Understanding this emotional mechanism allows therapists to trace the link between affect and behaviour, and to intervene with more precision. NA-CBT recognises that effective therapy cannot rely solely on cognitive restructuring. While important, cognitive work must be integrated with emotional and biological understanding. By working with both mind and body, NA-CBT can address the physiological roots of emotion, Normalise negative affect as adaptive rather than pathological and provide interventions that regulate both neurobiology and behaviour. This comprehensive approach enables clients to build true emotional resilience, not by avoiding difficult emotions, but by integrating and responding to them adaptively.

“Emotions are not problems to be solved; they are messages to be understood. NA-CBT helps decode these messages and transform them into healing.”

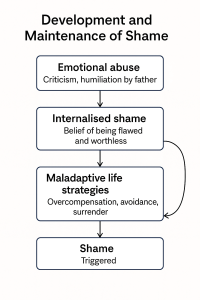

Shame-Based Disorders and Pervasive Emotional Challenges

A central focus of NA-CBT is the treatment of shame-based disorders, conditions often underrepresented or vaguely defined in clinical literature, yet deeply debilitating in practice. These disorders are characterised by persistent feelings of inadequacy, self-blame, self-loathing, or worthlessness. They may not fit neatly within traditional diagnostic categories, yet they underlie many presentations seen in therapy, including depression, anxiety, trauma-related symptoms, and personality difficulties. Such emotional states are often resistant to traditional CBT, as they stem from complex, long-standing affective patterns that are deeply embedded in the client’s emotional memory and physiological response systems. These patterns are frequently shaped by early attachment experiences, relational trauma, or repeated interpersonal invalidation.

NA-CBT responds to these challenges by targeting the neuroaffective dimension of shame-based disorders, addressing both emotional experience and its biological underpinnings.

Therapy protocols integrate:

- New learning and learning experiences aiming to enhances cognitive flexibility. Cognitive flexibility may be understood as the ability to adapt your thinking and behaviour when situations change, to shift between tasks, or to view problems from multiple perspectives. Research shows that novel learning stimulates brain plasticity, which strengthens the neural networks involved in executive functions, like attention control, working memory, and problem-solving (Liu, C. L. et al. , 2023; Gkintoni E. et al., 2025; Uddin, L. Q. , 2021).

- Psychoeducation (for example, life traps or education on hormones and nervous system regulation).

-

Cognitive restructuring of toxic beliefs (e.g., “I’m unlovable,” “I’m defective”).

-

Emotion regulation strategies tailored to shame and guilt or unwanted emotional experiences (identified outside of a diagnosable disorder).

-

Body-based and sensory practices aiming to interrupt stress responses and build interoceptive awareness.

-

Lifestyle interventions such as basic sleep hygiene, intense physical exercise and movement alongside relaxation, nutritional support and supplementation.

These combined approaches help clients regulate physiological stress more effectively and respond to emotional triggers, such as perceived rejection, failure, or abandonment, with greater resilience and clarity.

Evidence-Based Practices and Adaptability

NA-CBT is firmly grounded in the principles of evidence-based practice, drawing from a wide body of psychological and neuroscientific research to inform its methods. Techniques used within NA-CBT are supported by outcome studies in cognitive and behavioural therapy, research on affect regulation and trauma treatment, advances in neurobiology, particularly regarding neuroplasticity, emotional circuitry, and stress physiology. Yet what makes NA-CBT distinctive is not only its foundation in science but its capacity to evolve. As research continues to illuminate the intricacies of brain function and emotional processing, NA-CBT integrates these findings into its model. For example:

-

Neuroplasticity research informs how clients can rewire entrenched emotional patterns through repetition and emotional safety

-

Attachment and affective neuroscience guide relational techniques like empathic mentalisation

-

Studies on self-regulation and the autonomic nervous system shape interventions such as breathwork, attention-shifting, and somatic tracking

This adaptability ensures that NA-CBT remains clinically relevant and scientifically informed, offering practitioners and clients a model that is responsive to the complexity of modern psychological suffering.

“Rather than applying a fixed protocol to a static diagnosis, NA-CBT is a living, integrative model, one that grows in alignment with the science of healing and the realities of lived human emotion.”

Key Characteristics of NeuroAffective-CBT

NeuroAffective-CBT is a transdiagnostic-modular therapeutic model that has been developed and refined over the last 20 years by Daniel Mirea an experienced therapist who successfully integrates his broad academic and professional experience to fill a void and, help victims of various psychological problems difficult to diagnose. The approach emerged from a recognition of the limitations in existing diagnostic frameworks, such as the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) and ICD (International Classification of Diseases), particularly when it comes to addressing chronic mental health conditions that don’t fit neatly into specific diagnostic categories.

As such, the development of NA-CBT was driven by the need for a therapeutic model that could better understand and respond to individuals facing chronic mental health conditions that were transdiagnostic in nature. These conditions often involve deeply rooted emotions or affective experiences like shame, guilt or low self-esteem, that are difficult to categorise or diagnose using traditional psychiatric frameworks. In most cases, the network of maintaining factors problems that underlie these conditions are complex and confusing, making them challenging to address via self-help methods or conventional treatments.

It is important to note that in NeuroAffective-CBT, the terms affect and emotion are used interchangeably to describe biologically driven responses that influence behaviour and internal states. These are distinct from feelings, which are the conscious, often linguistic representations or interpretations of affective experiences essentially, the “symptom” or subjective reflection of an underlying emotional state. Such complex psychosomatic reactions are often difficult to articulate, particularly because the English language lacks the vocabulary to fully capture their nuance. For instance, certain cultures, such as Japanese, have precise words for emotions that remain unnamed in English, such as the emotion experienced after receiving a bad haircut. These nuanced, hard-to-translate emotional states often fall under broader experiential categories like low self-esteem, and may manifest as shame, self-loathing, or self-disgust—core affective experiences frequently addressed in NA-CBT.

On the other hand, psychotherapists may inadvertently contribute to client confusion by overestimating the average person’s understanding of emotional processes, such as the distinction between thoughts, emotions, and feelings. When clinicians avoid offering clear guidance or psychoeducation, despite it being a cornerstone of the cognitive and behavioural tradition, they risk reinforcing emotional uncertainty. This lack of clarity can unintentionally amplify distressing or poorly understood emotional experiences.

Because NA-CBT is not confined to treating a specific diagnosis and instead it opts for a transdiagnostic journey, the therapy plan addresses a broader range of emotional and psychological struggles that affect not only the sufferer but also those directly involved with them; for example someone that feels unattractive and not capable of sexual appreciation avoids the partner and any level of intimacy, in fear of rejection and disappointment. Over time the partner ends up feels equally unwanted and rejected – distance and lack of intimacy between the two, becomes the new normality. With such cases, the partner would also have to be involved in the therapeutic plan.

The approach is especially useful for individuals who experience a range of overlapping symptoms that cannot be fully explained by a single condition, such as anxiety, depression, trauma, or personality disorders. Transdiagnostic approaches were in fact promoted by clinicians like Meichenbaum, Beck, Barlow or Burns during the second-wave of CBT development in response to a range of symptoms that often cross the boundaries of a tight and specific diagnostic criteria. NA-CBT supports these views and attempts to further promote the notion that affective experiences such as shame, self-disgust or low self-esteem are at times inconsistent with DSM/ICD categories by displaying symptoms from both the hypo- and hyper-arousal spectrum and in fact low self-esteem can be observed in a range of categorised pathologies such as major depressive disorder, social anxiety, personality disorders, not to mention PTSD.

Modular framework

One of the defining features of NeuroAffective-CBT is its modular structure. Rather than following a fixed sequence of treatment stages, NA-CBT divides the therapeutic journey into flexible, interlocking modules. These modules, Assessment, Psychoeducation and Motivation, Physical Strengthening, Integrated-Self Development, Coping Skills and Regulation, and Consolidation and Future Planning, can be tailored to the individual’s clinical presentation, emotional needs, and capacity for learning.

This modular design offers several advantages:

- Customisation: Interventions can be adjusted to match the client’s readiness, goals, and specific psychological challenges.

- Fluid sequencing: Modules are not linear phases, but intersectable and interchangeable components. For instance, a client may begin therapy with Module 3 (Physical Strengthening) before engaging in Module 2 (Psychoeducation and Motivation), depending on the therapeutic formulation.

- Responsiveness to emerging needs: Therapists can move between modules as clinically indicated. If a client reveals unresolved childhood trauma during module 1, the Assessment phase, it may be therapeutically necessary to engage in trauma integration work (Module 4: Integrated-Self) sooner than planned, before returning to modules focused on resilience-building or psychoeducation.

This flexibility ensures the therapy remains responsive without losing coherence and allows for targeted intervention based on the client’s developmental trajectory within treatment.

For example:

- In the Physical Strengthening module, clients explore the connection between body and emotion. They are encouraged to monitor posture, somatic tension, and physical states, learning how bodily cues both reflect and shape emotional experience. The principle that “the mind instructs the body, and the body instructs the mind” is central here.

- Shame, in particular, may manifest in collapsed posture, restricted movement, or muscle rigidity. Therapists help clients develop awareness of these patterns and use somatic techniques to foster empowerment, energy, and emotional stability.

By working through these modules in either sequence or parallel, depending on the formulation, clients develop deeper internal awareness and greater psychological adaptability. The modular framework of NA-CBT is thus a dynamic map, not a rigid manual: it guides the therapeutic process while allowing for creativity, attunement, and clinical judgement.

Chronic and Complex Emotional Experiences

The model specifically addresses chronic mental health conditions that are often undetected or overlooked in traditional clinical settings. Individuals suffering from these conditions may experience ongoing emotional distress that is not clearly linked to a specific diagnosis. These emotional challenges are often marked by persistent negative affects and recurring stress that can feel unmanageable. Such clients often struggle with shame, self-loathing, guilt, and low self-esteem, making it difficult for them to identify and articulate the emotional roots of their struggles.

Neuroaffective research points out that an integrated or balanced sense-of-self, improvements in confidence and well-being could be achieved through better hormonal regulation and associated learning. This type of research which includes biology and physiology, sleep research, neuroimaging analysis and so on, has influenced CBT treatments over the recent years and continues to shape therapists’ understanding of neuroplasticity, neurotransmitters, hormonal regulation and even the role of gut and microbiome in our mental health.

By incorporating neuroscientific insights, NA-CBT allows individuals to better understand how neuroplasticity (the brain’s ability to change and adapt) can be harnessed to help reshape maladaptive emotional responses. The approach focuses on fostering new neural connections that can lead to more positive emotional experiences and improved overall well-being. People who face these chronic conditions may have a history of painful emotional experiences, often with relatively rare breaks of wellness. The difficulty in pinpointing the triggers for emotional distress can make it even harder for these individuals to find relief or solutions. These affective experiences are often complex and intertwined, making it challenging to distinguish clear boundaries between emotions like anger, sadness, fear, and shame. The emotional experience of these individuals is often ambiguous or non-specific, which means that their distress does not always fit neatly within the confines of a conventional diagnosis. This can leave clients feeling lost, misunderstood, and without clear guidance or support.

An overview of the therapy toolkit

Module 1: Assessment and case formulating – this foundational stage is where the therapeutic journey begins, with the primary focus on building trust and establishing a collaborative relationship. It provides the ideal opportunity to introduce some of NA-CBT’s unique conceptual tools, such as “empathic-mentalisation”, a technique for deeply understanding the client’s lived experience, and the “Pendulum Effect”, a dynamic case formulation model that maps the oscillation between affect-driven coping behaviours.

As with all CBT-based approaches, NA-CBT starts with a comprehensive assessment, not only to identify symptoms and risk factors, but to develop a personalised case formulation that will inform and guide the entire treatment plan. This stage is not optional, it is a core therapeutic condition. Without a clear, collaboratively developed formulation, therapy lacks structure and direction. In NA-CBT, assessment is not merely diagnostic; it is relational, emotional, and deeply attuned to the client’s cognitive, affective, and neurobiological context.

The assessment and case formulation are critical components of the therapeutic process. NA-CBT emphasises that, this initial stage requires detailed, empathic listening with timely sensitive observations, it is perhaps the most important stage in the therapy. Without a thorough assessment and case formulation, therapy lacks direction, “much like steering a boat without a rudder”, a concept famously articulated by Donald Meichenbaum. This initial phase of the NA-CBT process is not simply about understanding the client’s risk factors and maintenance symptoms and eventually formulating a treatment plan. But it is primarily about enabling a strong therapeutic alliance and establishing a trusting relationship between the therapist and the client. In NA-CBT, this is achieved by using methods unique to this approach, such as empathic-mentalisation which incorporates method-acting techniques like being able to step into client’s world and embody their lived experience, feelings, actions and thoughts. Empathic mentalisation is a term coined by Daniel Mirea to describe therapist’s deep understanding of client’s emotional world and thought processes. This technique helps the therapist to engage with the client in a way that validates their experience, while also facilitating greater self-awareness in the client. It aids in exploring not just the content of thoughts, but the emotional and neurobiological context in which these thoughts arise. This process often means feeling victims’ pain and truly seeing the world though their eyes, crucial in helping a victimised client feel understood, supported, and safe to engage with the difficult therapeutic work ahead.

Building this strong therapeutic relationship during the initial phase of NA-CBT also serves to create a secure and collaborative environment where the client can be open about their difficulties. This relationship is foundational to the effectiveness of the treatment, as it fosters the necessary trust for the client to explore complex and sometimes painful emotional material. Through empathetic mentalisation, the therapist is able to essentially feel client’s psychological pain and align more closely with the client’s lived experience, ensuring that the case formulation is not just a clinical process, but one that reflects the client’s personal, emotional, and psychological world. In this way, NA-CBT integrates empathy and understanding into the therapeutic process, enhancing the overall effectiveness of the treatment and helping clients navigate their emotional challenges more effectively.

Module 2: Psychoeducation & Motivational Enhancement:

This module marks yet another foundational turning point in NA-CBT, where clients begin to actively engage with the knowledge, insight, and motivation necessary for sustainable emotional growth. The aim is to equip clients with a working understanding of their emotional, cognitive, and physiological patterns, while enhancing self-efficacy, resilience, and readiness for change.

Objectives of Module 2

- Build Insight: Help clients make sense of their psychological experiences using clear, relatable explanations.

- Enhance Self-Efficacy: Foster the belief that they can influence their emotional responses and life outcomes.

- Strengthen Motivation: Reinforce the reasons for seeking change and develop a values-based commitment to the therapy process.

- Develop Problem-Solving Skills: Introduce structured, practical strategies for addressing everyday challenges and emotional setbacks.

Core Components

- Tailored Psychoeducation

- Clients are introduced to basic neurobiological and psychological concepts (e.g., the stress response, emotion regulation, cognitive distortions, affective loops).

- Information is personalised, not generic: explanations are linked directly to the client’s case formulation and symptoms (e.g., understanding shame as a self-regulatory emotion, or avoidance as a short-term coping strategy that reinforces anxiety).

- This empowers clients to understand that their experiences are not “pathological,” but meaningful, predictable, and modifiable.

- Clarifying Thoughts vs. Emotions vs. Feelings

- Many clients enter therapy without a clear understanding of the differences between these core concepts.

- The therapist helps them disentangle cognitive processes from emotional and somatic experiences, increasing emotional literacy.

- Exercises may include labelling emotions accurately, distinguishing feelings from judgments, or tracking internal responses to interpersonal triggers.

- Values Clarification & Motivational Mapping

- Clients identify what truly matters to them, relationships, creativity, safety, achievement and, map out how their current emotional difficulties interfere with those values. Learning to live life “as if “… the opposite of what the internalised shame is suggesting: “I am capable of receiving appreciation”.

- Therapists may use tools such as motivational interviewing techniques, the “Values Compass,” or structured reflection to enhance intrinsic motivation.

- This creates a purpose-driven rationale for treatment: “I’m not just managing anxiety; I’m learning to live a fuller, more aligned life.”

- Expectancy and Hope Building

- Hope is a clinically relevant predictor of engagement and outcome.

- The therapist fosters hope by explaining neuroplasticity (i.e., the brain can change), the evidence-base of CBT principles, and by reinforcing early wins or shifts in awareness.

- Problem-Solving and Decision-Making Skills

- Clients learn to identify avoidant or impulsive patterns and replace them with structured, proactive approaches.

- Techniques may include cost-benefit analysis, or structured decision trees.

- As they practice solving real-life issues in therapy, their sense of competence and autonomy increases.

Therapist Role and Therapeutic Tone

- The therapist takes a collaborative but directive role, offering clear information, compassionate feedback, and concrete strategies.

- Therapeutic communication is normalising, hopeful, and validating, balancing scientific explanation with empathy.

- Frequent check-ins ensure the pace, depth, and content of psychoeducation are aligned with the client’s cognitive and emotional readiness.

“The psychoeducation stage sets the intellectual and motivational groundwork for deeper emotional processing and behavioural change. In NA-CBT, psychoeducation is not an optional add-on, it is a core therapeutic intervention that empowers the client to become an active participant in their healing process.”

Module 3: Physical Strengthening:

“TED’s your best friend!”. A symbol of much needed lifestyle changes.

In NeuroAffective-CBT, physical wellbeing is inseparable from emotional resilience. Module 3 focuses on strengthening the body to support affect regulation and psychological adaptability. To make this concept practical and memorable, NA-CBT introduces TED a simple, symbolic and imaginary guide that clients can use daily to reflect on essential lifestyle habits that directly impact mood and emotional functioning. Drawing inspiration from the popular film character, a loyal and lively teddy bear, TED becomes a metaphorical ally for clients. In therapy sessions, catchphrases like “TED’s your best friend” and “When in doubt, check with TED!” serve as accessible cues to reinforce the importance of routine self-care. TED helps clients remember that small, consistent physical actions can have powerful psychological effects.

Tired (energy levels and sleep deprivation)

Exercising (physical exercises scheduling)

Diet (nutritional habits: drinking & eating)

TED offers more than a checklist—it encourages self-monitoring, fosters self-efficacy, and highlights the role of daily physical care in maintaining emotional regulation and overall mental health.

This acronym serves as a quick and relatable check-in tool:

-

Tired: Am I sleep-deprived? Is my energy low?

-

Exercise: Have I been active or moved my body at all lately? Was I too ‘static’ at work this week?

-

Diet: How well am I eating and hydrating? Have I skipped meals or relied on comfort foods? Did I have enough water or too many sugary and caffein drinks? What about alcohol in the evening? How many shots are in a ‘night cap’?

Clinical purpose and supporting evidence for TED

-

Improve affect regulation through better sleep, exercise, and nutrition

-

Build resilience by supporting the body’s stress response system

-

Enhance self-appreciation through embodiment and physical awareness

-

Boost immunity and emotional energy by addressing biological needs

-

Prevent or reduce dysregulation by managing known physiological risk factors

One of the most compelling features of NA‑CBT is the TED module focusing on Tiredness, Exercise, Diet, each demonstrating strong empirical links to emotional and cognitive wellbeing:

Tired: Poor sleep disrupts emotion regulation and brain function. Insomnia is closely linked to increased emotional reactivity and reduced cognitive control, heightening vulnerability to mood disorders (Baglioni et al., 2011). Later school start times, which improve sleep quality in adolescents, have been associated with better academic performance and emotional health (Alfonsi et al., 2020).

Exercise: Regular physical activity, particularly aerobic exercise, has been shown to significantly reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety. Exercise promotes emotional regulation, lowers cortisol levels, and enhances neuroplasticity—effects comparable in some cases to antidepressant medication or psychotherapy (Kandola et al., 2019; Craft & Perna, 2004).

Diet: A high-quality diet, rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and omega-3 fatty acids, has been linked to better emotional resilience and lower risk of depression. Meta-analyses and large-scale population studies show that dietary patterns directly influence inflammatory markers and neurotransmitter function involved in mood regulation (Lassale et al., 2019; Jacka et al., 2011).

A recent study surveying university students reinforced the combined impact of these three components on mental health: it found that poor sleep, suboptimal diet, and low physical activity were each independently associated with poorer cognitive function, emotional regulation, mood, and stress resilience (p < .05 in all cases); (Schlitt, Downes, Young, & James, 2022).

By embedding empirical findings into the TED framework, NA‑CBT demonstrates both depth and scientific integrity, bridging theory, neuroscience, and lifestyle-based interventions. This strengthens the model’s relevance in addressing emotion regulation challenges—especially shame-based issues, within a comprehensive, evidence-informed treatment structure.

Therapist’s Role

Therapists introduce TED early in treatment and reinforce its relevance throughout therapy. It is particularly useful when clients report low motivation, mood fluctuations, or physical symptoms linked to emotional states (e.g., fatigue, headaches, irritability). TED provides a non-judgmental starting point for conversations about lifestyle patterns, and a pathway for gently challenging passive or avoidant behaviours.

“By strengthening the body, clients increase their capacity to face emotional challenges with greater stability, confidence, and energy. TED is not just a reminder, it is a practical, empowering companion on the path to wellness.”

Module 4: Development of the ‘Integrated-Self’:

This is a particularly pivotal stage in NeuroAffective-CBT, as it addresses the profound disconnect that often exists between the way an individual perceives themselves and how they aspire to be. For many clients, internal shame and self-loathing create a split between their present self, who they believe themselves to be, often burdened by negative self-judgments, and their ideal self, who they would like to be, often a version of themselves full of potential, self-worth, and emotional balance. This stage seeks to bridge that gap by fostering integration between these two parts of the self, leading to a more unified, authentic, and emotionally resilient identity.

Key Components of Integration:

Cognitive Reframing and Self-Reintegration

A central element of this phase is early trauma processing and cognitive reframing, which involves helping clients shift how they perceive themselves and their experiences. By identifying deeply-rooted beliefs, often rooted in shame, guilt, or self-criticism, the therapist guides the client in replacing these with more balanced and compassionate interpretations.

This cognitive work is coupled with reintegration, the process of reconciling the fragmented parts of the self. Clients begin to accept past mistakes, perceived flaws, and emotional vulnerabilities not as defects, but as parts of their human experience. This creates a coherent self-narrative, allowing clients to hold both their strengths and limitations with empathy and acceptance.

“The goal is not perfection, but wholeness”.

Self-Acceptance and Self-Compassion

For clients with histories of trauma, rejection, or emotional neglect, self-hatred and self-criticism often become internalised defaults. This stage supports a shift toward self-acceptance and self-compassion, helping clients treat themselves with the same empathy they might extend to someone they love.

Key techniques include:

-

Challenging internalised beliefs such as “I’m not good enough” or “I’m fundamentally broken.”

-

Promoting self-kindness through reflection, guided imagery, and affirmation work.

-

Encouraging self-care practices that nurture both physical and emotional well-being.

Through this work, clients begin to transform their internal dialogue—from one of blame and shame to one of understanding and encouragement.

Processing Traumatic Memories

Unresolved trauma often contributes significantly to a fractured sense of self. To create a truly integrated identity, these experiences must be processed—not avoided or overwritten, but acknowledged, understood, and reframed.

NA-CBT uses several trauma-informed techniques to support this process:

-

Bilateral Stimulation: Drawing from EMDR principles, this technique engages new learning with attention-orientation and associated psychosomatic reactions to reduce emotional reactivity and desensitise traumatic memories.

-

Narrative Exposure: Clients are supported in recounting their life stories, integrating difficult experiences into a coherent personal narrative that reduces the emotional charge of shame and fear.

-

Reliving and Reprocessing: When appropriate and safe, clients are guided to revisit distressing memories in a controlled therapeutic environment, allowing them to reconceptualise past events and reclaim agency over their stories.

These methods help clients externalise trauma, reducing its internal grip and making space for new, empowering interpretations of the self. The neuroaffective mechanisms at play are complex, involving dopaminergic activation that supports motivation, learning, and the positive reinforcement of new interpretations of the self. In parallel, the noradrenergic system, which produces norepinephrine and, peripherally, epinephrine – often referred to as noradrenaline and adrenaline, regulates arousal and adaptive anxiety, allowing the individual to remain alert without becoming overwhelmed, like “the fear of failing a test and studying hard as a result”. This type of stress is expected and does not typically lead to behavioural avoidance. Furthermore, this balance enables trauma memories to be reprocessed in ways that feel safe yet transformative.

Toward Wholeness and Emotional Resilience

The ultimate aim of this module is the reconciliation of the fractured self. The client is no longer divided between who they are and who they wish to be, but instead grows into a more integrated, emotionally balanced person, one capable of embracing both vulnerability and strength.

Through trauma resolution, self-compassion, and cognitive reintegration, clients:

-

Develop a stronger and more stable identity

-

Align their thoughts, emotions, and behaviours with their personal values

-

Experience increased emotional flexibility and resilience

-

Build the foundation for long-term well-being and psychological growth

“Integration is not the erasure of pain, but the ability to hold pain and peace together in the same truth.”

This phase often becomes a turning point in therapy, where shame gives way to dignity, and the past becomes a source of strength rather than suffering.

Module 5: Coping Skills Training & Self-Regulation:

This module is dedicated to equipping clients with a practical, adaptable toolkit for emotional regulation, behavioural activation, and everyday functioning. Drawing from the strength of traditional behaviour therapy and enriched by the latest findings in neuroscience, this phase empowers clients to implement real-world strategies that foster stability, resilience, and self-direction.

The tools and interventions introduced here go beyond symptom relief, they aim to help clients shift their lifestyle, challenge unhelpful behavioural patterns, and respond more flexibly to internal and external triggers.

Bridging Behaviour Therapy and Neurobiology

The techniques used in this module reflect a hybrid approach: they integrate the proven efficacy of behavioural strategies (such as exposure, assertiveness, and habit formation) with neurobiological principles that promote emotional and attentional regulation.

Clients learn how emotion-driven reinforcing behaviours (EDRBs), actions taken to soothe or escape emotional discomfort, often perpetuate avoidance and distress. By making this process explicit through tailored psychoeducation, clients are supported in identifying when these behaviours arise and how to respond differently.

Key Therapeutic Tools:

-

Tailored Psychoeducation – therapy here is not one-size-fits-all. Educational strategies are carefully linked to the client’s unique formulation and emotional profile. This helps demystify emotional reactions and builds cognitive insight into how behavioural patterns are maintained (i.e., EDRB’s and vicious cycles); the function of avoidance or safety behaviours; the role of attentional bias and misinterpretation.

-

Behavioural Techniques

-

Assertiveness Training: Developing confident, non-defensive communication skills

-

Graded Exposure Plans: Facing feared situations in a planned, progressive way

-

Behavioural Activation: Engaging in meaningful activities to counteract withdrawal or passivity

-

- Mind-Body Integration

-

-

Breathwork and Body Awareness: Using interoceptive tools to manage arousal

-

Mindfulness Practices: Developing non-judgmental awareness of present experience

-

Self-Hypnosis and Guided Relaxation: Facilitating deep calm and focused attention, understanding progressive muscle relaxation

-

-

Cognitive and Executive Skills

-

Problem-Solving Training: Building structured approaches to tackling real-life challenges

-

Decision-Making Strategies: Strengthening judgment, especially when emotion is high

-

Attention-Training: Shifting attentional control away from threat cues or internal preoccupation

-

-

Ongoing use of NA-CBT specific concepts

-

Empathic-Mentalisation continues as a relational tool, helping clients regulate emotion by feeling understood and reflected

-

EDRB awareness is applied actively, allowing clients to replace avoidance loops with adaptive coping

- TED‘s your best friend !

-

Encouraging Calculated Risk and Trust in the Therapeutic Process

One of the most significant psychological shifts in this phase involves encouraging clients to act against familiar gut-instincts, such as avoiding conflict, suppressing emotion, or retreating from social engagement. Taking calculated interpersonal or emotional risks requires:

-

Trust in the therapist and therapeutic process

-

Belief in personal capacity for change

-

Willingness to tolerate short-term discomfort for long-term growth

The therapist’s role is to support and scaffold these efforts, providing clear rationale, modelling confidence, and reinforcing every success.

Outcome: Practical Mastery for Real-Life Application

By the end of this phase, clients should:

-

Possess a robust toolkit of practical self-regulation strategies

-

Feel capable of confronting emotional and interpersonal challenges

-

Be increasingly confident in their ability to manage distress without resorting to old coping patterns

This module serves as a vital bridge between insight and action, ensuring that the emotional and cognitive gains achieved in earlier modules are not only preserved but also translated into meaningful, day-to-day application. However, it is essential to emphasize that the ‘numbered’ modules in NA-CBT do not represent fixed stages of treatment. Instead, they are flexible, intersecting components of a modular framework that can be adapted to the client’s evolving needs, formulation, and therapeutic readiness. For instance, an exposure plan might be introduced much earlier in the process if clinically indicated by the case formulation, current social context, or strength of the therapeutic alliance.

Module 6: Skills Consolidation and Relapse Prevention:

Module 6 represents the final stage in the NA-CBT process. It is a critical phase designed not only to preserve the therapeutic gains achieved during treatment but to equip clients with the confidence, insight, and self-efficacy needed to sustain these gains long after therapy concludes. This phase focuses on integration, application, and anticipation, bringing together everything the client has learned, helping them apply these insights in their everyday life, and preparing them to face future challenges with resilience.

Reconnecting with Values and Renewed Commitments

At the heart of long-term change lies clarity of purpose. In this phase, the therapist supports the client in revisiting the values and motivations that initially brought them into therapy. This process helps clients:

-

Reaffirm the goals and personal values that now shape their decision-making

-

Recognise how therapy has helped them align behaviour with core beliefs

-

Strengthen their sense of direction moving forward

This reflective work reinforces meaning and intrinsic motivation, which are vital for sustaining emotional growth and resilience outside the therapy room.

Identifying Triggers and Planning for Relapse

Relapse is not failure, it is a foreseeable part of the human experience. NA-CBT takes a proactive, compassionate approach to preparing for potential setbacks.

Together, therapist and client:

-

Identify high-risk situations (e.g., social rejection, work stress, loss of routine)

-

Recognise early warning signs of emotional dysregulation or cognitive distortions

-

Develop a personalised relapse prevention plan, which may include:

-

Rehearsing coping responses

-

Creating support structures

-

Strategising for re-engagement with therapeutic tools when needed

-

By normalising and planning for relapse, clients reduce fear and shame associated with potential setbacks, empowering them to navigate challenges confidently and skillfully.

Reinforcing Core Skills and Building Confidence

This phase includes a structured review of the coping strategies and tools introduced throughout the modules, such as:

-

Cognitive reframing and thought-challenging

-

Emotional regulation practices

-

Body-based interventions (e.g., TED: Tired, Exercise, Diet)

-

Mindfulness, self-hypnosis, and attention regulation

Clients are encouraged to apply these tools in real-life scenarios, reinforcing skill mastery and increasing self-trust in their ability to manage distress. This practical rehearsal helps convert therapeutic insight into habitual action.

Sustaining Growth and Fostering Self-Efficacy

Ultimately, this module aims to transition the client from therapist-supported growth to self-directed resilience. The focus shifts from treatment to personal leadership of one’s mental and emotional well-being.

The outcomes of this phase include:

-

A sense of mastery over previously overwhelming emotions

-

A coherent, values-aligned sense of identity

-

A robust toolkit for maintaining progress and adapting to future demands

“Therapy doesn’t end when sessions do, it continues in every moment where the client chooses clarity over confusion, compassion over criticism, and values over fear.”

This final stage affirms the client’s capacity for lifelong growth, giving them the tools and inner confidence to not only maintain but build upon the work achieved in therapy.

Final thoughts…

NeuroAffective-CBT represents a significant advancement in the field of psychotherapy, offering a transdiagnostic, modular framework that is specifically designed to address chronic, complex, and difficult-to-diagnose mental health conditions. Developed by Daniel Mirea, this approach draws from decades of research in psychology, neurobiology, and emotional regulation, making it a powerful tool for treating individuals who struggle with deeply rooted emotions like shame, guilt, and self-loathing. Its flexibility, combined with an in-depth understanding of the brain’s emotional processes, makes NA-CBT an effective treatment for those facing long-standing emotional challenges that have often eluded conventional therapy.

Clarification of Key Terms

-

Neuroaffective: Refers to the integration of neurological and emotional processes. In NA-CBT, this implies working with both the brain’s physiological responses and the client’s emotional experiences.

-

Emotion-Driven Reinforcing Behaviours (EDRBs): Behaviours that are driven by emotional discomfort and serve to reinforce avoidance or maladaptive regulation strategies. Example: withdrawing socially after shame to avoid judgment.

-

Empathic-Mentalisation: A therapeutic stance in which the therapist actively imagines and embodies the client’s internal world—thoughts, feelings, intentions—in a way that fosters safety, insight, and emotional regulation.

-

Affect vs. Emotion: In NA-CBT, the terms “affect” and “emotion” are used interchangeably to describe biologically rooted responses that motivate behaviour. They are distinct from “feelings”, which are the conscious, often language-based interpretations or subjective awareness of those affective states. Feelings are seen as the somatic or experiential result of an underlying affect.

References

Alfonsi, V., Scarpelli, S., D’Atri, A., Stella, G., & De Gennaro, L. (2020). Later school start time: The impact of sleep on academic performance and health in the adolescent population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2574. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072574

Baglioni, C., Battagliese, G., Feige, B., Spiegelhalder, K., Nissen, C., Voderholzer, U., … & Riemann, D. (2011). Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 135(1–3), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011

Craft, L. L., & Perna, F. M. (2004). The benefits of exercise for the clinically depressed. Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 6(3), 104–111. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.v06n0301

Duarte, C., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Ferreira, C. (2015). The role of psychological inflexibility in the link between shame and psychopathology in clinical and non-clinical samples: A path analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 22(6), 674–682. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1925

Elhai, J. D., Levine, J. C., & Hall, B. J. (2017). Problematic smartphone use and mental health: Current state of research and future directions. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.027

Gkintoni, E., Vassilopoulos, S. P. & Nikolaou, G. (2025) ‘Brain-inspired multisensory learning: A systematic review of neuroplasticity and cognitive outcomes in adult multicultural and second language acquisition’, Biomimetics, 10(6):397. doi:10.3390/biomimetics10060397 MDPI

Kandola, A., Ashdown-Franks, G., Hendrikse, J., Sabiston, C. M., & Stubbs, B. (2019). Physical activity and depression: Towards understanding the antidepressant mechanisms of physical activity. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 107, 525–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.09.040

Kross, E., Berman, M. G., Mischel, W., Smith, E. E., & Wager, T. D. (2011). Social rejection shares somatosensory representations with physical pain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(15), 6270–6275. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1102693108

Jacka, F. N., Mykletun, A., Berk, M., Bjelland, I., & Tell, G. S. (2011). The association between habitual diet quality and the common mental disorders in community-dwelling adults: The Hordaland Health Study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73(6), 483–490. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e318222831a

Lanius, R. A., Bluhm, R., Lanius, U., & Pain, C. (2006). A review of neuroimaging studies in PTSD: Heterogeneity of response to symptom provocation. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 40(8), 709–729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.07.007

Liu, Q., Zhou, Z., Yang, X., Kong, F., & Niu, G. (2023). Mobile phone addiction and emotion regulation strategies: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors, 137, 107534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107534

Liu, C. L. et al. (2023) ‘Potential cognitive and neural benefits of a computerised Structure Learning intervention on cognitive flexibility: study design of a randomised controlled trial’, Trials, 24, Article 330. doi:10.1186/s13063-023-07551-2 BioMed Central

Lassale, C., Batty, G. D., Baghdadli, A., Jacka, F., Sánchez-Villegas, A., Kivimäki, M., & Akbaraly, T. (2019). Healthy dietary indices and risk of depressive outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Molecular Psychiatry, 24, 965–986. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0237-8

Meichenbaum, D. (2006). Resilience and posttraumatic growth: A constructive narrative perspective. In L.G. Calhoun & R.G. Tedeschi (Eds.), Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research and practice (pp. 355–368). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Meichenbaum, D. (2012). Roadmap to resilience: A guide for military, trauma victims and their families. Clearwater, FL: Institute Press.

Mirea, D. (2018, July 25). CBT, what’s all the fuss about? NeuroAffective‑CBT. Retrieved from https://neuroaffectivecbt.com/2018/07/25/cbt-whats-all-the-fuss-about/

Mirea, D. (2018, July 26). Third‑Wave CBT or three waves of CBT? NeuroAffective‑CBT. Retrieved from https://neuroaffectivecbt.com/2018/07/26/third-wave-cbt-or-three-waves-of-cbt/

Schlitt, J. M., Downes, M., Young, A. I., & James, K. (2022). The “Big Three” health behaviors and mental health in university students. The Canadian Review of Social Studies, 9(1), 13–27. https://thecrsss.com/index.php/Journal/article/view/298

Tang, Y. Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3916

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2018). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive Medicine Reports, 12, 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.003

Uddin, L. Q. (2021) ‘Cognitive and behavioural flexibility: neural mechanisms and clinical considerations’, Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 22(3), pp. 167–179. doi:10.1038/s41583-021-00428-w PMC+1

Zhou, H., Wang, M., Yang, J., & Yang, L. (2022). The relationship between mobile phone addiction and emotional disorders: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 986395. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.986395

Zheng, D., Liu, H., & Liu, Y. (2023). Smartphone use and cognitive failures: The mediating roles of mind-wandering and sleep disturbance. PLOS ONE, 18(3), e0282676. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282676

Zilverstand, A., Parvaz, M. A., & Goldstein, R. Z. (2017). Neuroimaging cognitive reappraisal in clinical populations to define neural targets for enhancing emotion regulation: A systematic review. NeuroImage, 151, 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.06.009

Where can you get training in NA-CBT

In London and online, an overview of NeuroAffective-CBT® techniques are offered on request to all UKCHH graduates but also post-graduate and doctoral students in Integrative Psychotherapy @Regents University or @Existential Academy via NSPC-Middlesex University. In-depth certificated training in I-CBT and NA-CBT can certainly be offered to any training organisation that may be interested. Daniel Mirea can easily be reached on this website, his email address (therapy@danmirea.co.uk) or at UKCHH where he regularly teaches – UK College of CBT & Hypnosis – this college is focused on Hypno-CBT, CBT and evidence-based psychology only, it could well be the only college in London that has taken a lead in Integrative-CBT methods (aka 4th wave-CBT) under Daniel Mirea, Donald Meichenbaum and Mark Davis’s guidance. Since this is advanced cognitive-behavioural training and the approach places itself falls under the umbrella of I-CBT therapies, it is not presently offered outside the psychological, psychiatric and CBH community which means that one would have to have a core mental health profession or to at least be accredited in Cognitive-Behavioural Hypnotherapy (CBH) before attending training in NA-CBT.